The 1958-'61 South American Triangular Tournaments

- Where front-engined Formula One went to die

Part 2: First edition of the South American Triangular Championship (1958-'59)

Author

- Lorenzo Baer

Date

- August 14, 2024

Related articles

- The 1958-'61 South American Triangular Tournaments - Where the front-engined F1 went to die, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1934-'37 Rio GPs - Postcards from Gavea, by Mario Cesar de Freitas Levy/Leif Snellman/Antonio Carlos Barque de Lima

- 1949 Brazilian Temporada - Brazil's forgotten racing days, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1950 Chilean GP - The first, the last and the only, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1966 Argentinian F3 Temporada - It's never too late to revive old passions, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1967 Argentinian F3 Temporada - Time to go south again!, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1968 Argentinian F2 Temporada - The quick dash of the Cavallino Rampante in the Argentinian Pampas, by Lorenzo Baer

Who?Ramón Requejo, José Froilán González What?Requejo-Corvette, Ferrari-Corvette 625 Where?Interlagos When?1958 Prefeito Adhemar de Barros Trophy |

|

Why?

- Back to part 1: Introduction - A very peculiar championship

Race 1: Prêmio Prefeito Adhemar de Barros

It was expected that the first Triangular Tournament would be held in the first part of 1958, with the race dates adapting to the national calendars of each country involved in the championship. However, as negotiations on prizes and regulations took longer than initially planned, it was decided that the Triangular would be split between the end of 1958 and the beginning of 1959. In 1958, only the Brazilian race would be contested, with the expectation that the other two legs of the championship would be held in the first months of the following year.

Because of this, both the ACB and Ângelo Juliano were quick to organise the event on the Interlagos circuit, not wanting to delay once again the start of the competition. Scheduled for the end of November 1958, the organisers of the race had as their main challenge attracting the main national motorsport stars from Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina. Forging agreements with automobile associations in each country, in the end, the result proved to be quite surprising, in the positive aspect of the word.

Representing Brazil, drivers Fritz D'Orey (Ferrari 375/Corvette), Paschoal Nastromagario (Ferrari 125/Corvette) and Ciro Cayres (Ferrari 195S/Corvette) were selected. Of these, Cayres was the most experienced, having a racing career that could be traced back to 1950. The driver had participated in more than two dozen races, almost all of them on the Brazilian national scene. However, Cayres had also had some minor international appearances, such as in the 1957 edition of the 1000km of Buenos Aires (when the driver finished in 19th position) and in the 10 Hours of Messina in 1955 (where Cayres was registered to share a Ferrari 500 with Italian driver Gino Munaron but ended up not appearing). The machine that the driver would guide throughout the season would be a Ferrari 195, which had its sports-type body removed to make way for a single-seater body built entirely in Brazil.

Despite enjoying greater fame at that time, Cayres would not be the most recognised name on this list for a more attentive observer. Fritz d'Orey is certainly the one who catches the reader's attention, largely due to the Teuto-Brazilian's participation in some of the most important races and categories in world motorsport. For example, d'Orey would drive in F1 for Centro Sud and Camoradi in 1959, in addition to participating in the Sebring 12 Hours and the Le Mans 24 Hours. However, this was still just a dream in the driver's career, who in 1958 was only in his second year as a professional driver.

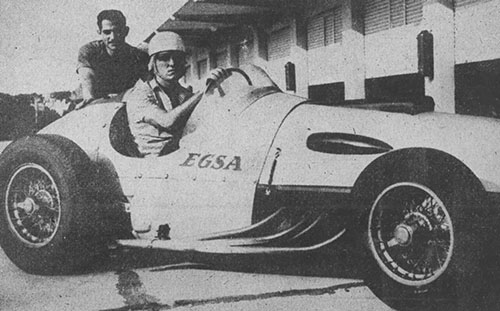

Closing the list of Brazilians was Nastromagario. Like d'Orey, Paschoal was only in his second year as a professional driver and had been chosen for official Brazilian representation only because many of the other highly rated and experienced Brazilian drivers were unavailable for the race. The driver had achieved some modest results in 1957, but the purchase of a 'new' vehicle by Paschoal (the ex-'Chico' Landi Ferrari 125) at the end of the year had substantially increased the driver's performance throughout 1958 – something that partially explains why the driver had been chosen by the ACB.

From the Uruguayans, a very solid contingent of drivers was also highlighted: Osmar Mario Gonzalez (Ferrari 375/Corvette), Asdrúbal Bayardo (Maserati 4CLT-48/Chevrolet) and Carlos Danvilla (Ferrari 500/Corvette). All the drivers had decent international experience, especially in neighbouring Argentina, where Fuerza Libre races had spread throughout the country. Bayardo, the pioneer of the Mecânica Nacional, was the main exponent of this group, having participated in races in the category since the early 1950s – often aboard his veteran Maserati, which had now completed almost ten years of continuous service.

But the biggest stars would undoubtedly be the representatives who came from the other side of the Rio de la Plata. The Argentinians were really aiming for the victory in the Brazilian race. Jesús Iglesias (Pian/Chevrolet), Ramón Requejo (Requejo/Corvette) and José Froilán González (Ferrari 625/Corvette) prepared to embark on this adventure in the country of samba.

Paschoal Nastromagário and his chief mechanic, Toninho Versa, pose for a photo with the Ferrari 125 that Nastromagário would use in the 1958-'59 Triangular. (credits unknown)

Both Requejo and Iglesias had become some of the finest Argentine drivers by the end of the 1950s, having each achieved several successes in the Fuerza Libre races held in their home country and even abroad; for example, Requejo won the Mecânica Nacional race organised for the 50th Anniversary of the Automóvel Clube do Brasil, held in São Paulo – Brazil – in 1957. Ramón Requejo was the current defending champion of the Argentine Fuerza Libre title (1957) while Jesús Iglesias had won the Fuerza Limitada title (a subcategory of the Libre) in 1951. In a face-to-face, Requejo had won seven races between 1957 and 1958 while Iglesias had scored three triumphs in the same space of time.

However, it was former F1 driver Froilán González who attracted the attention of the media and the public. After seven years in the highest-level international automobile categories (such as F1, F2 and WSC) González decided to return to his origins at the end of 1957. For the driver, Formula One had completely changed since his debut in 1950, and it was time to open the way for a new generation of drivers. Furthermore, the constant comparisons with his more successful compatriot, Juan Manuel Fangio, took a toll on the driver's career, as he always found himself in the shadows of his rival and friend.

With this perspective in mind, González chose to leave F1 and other international categories, with the clear objective of dominating for one last time the Argentine motorsport scenario. After purchasing one of the Ferrari 625s that previously belonged to Scuderia Ferrari (and which González himself had driven for the team between 1954-'55) the driver set sail towards his homeland and, upon his arrival, González made an impact, demonstrating that 'El Toro de los Pampas' was still an opponent to be feared. At the end of 1957, the driver had already scored his first triumph on his return to the south (with the 625 already equipped with a Corvette engine), winning an international Fuerza Libre race held in El Pinar.

In his first full season in the Argentine Mecánica Nacional, in 1958, the driver had accumulated many achievements: three victories in Buenos Aires, one in Rafaela and one in El Pinar, which put the driver very close to the Argentine title in the category. Therefore, the call from the ACA for the formation of an Argentine representation that was heading towards Brazil, seemed like an opportunity too good for the Argentinian to pass – and so it was, with Gonzalez spearheading the Argentine trio in Interlagos.

In addition to these nine drivers, another seven signaled positively to participate in the race, bringing the total number of drivers registered for the first stage to 16. The strongest of these outsiders was certainly Luiz Américo Margarido, who had entered the race with one of the few Talbot T26Cs that arrived in Latin America. With chassis plate number #110008, this car was ex-Etancelin and brought to Brazil by French driver Jean Achard in 1951. The car had passed through the hands of some drivers in the interim, until it was acquired by Margarido in 1958, who equipped it with a Cadillac engine.

But Margarido proved to be an exception among these drivers who would add volume to the grid, as many of the race's complementary wildcard entries were Brazilian-made single-seaters or touring cars adapted to operate in Formula Libre races. Because of this, the ACB decided to divide the vehicles into two categories: the first would encompass cars with up to 2500cc (which were generally equipped with Lancia, Ford and MG engines) while the second would be open to cars with up to 4500cc (such as Corvette, Chevrolet and Cadillac).

The race to define the first trophy of the championship (which was named Prêmio Prefeito Adhemar de Barros) was scheduled to take place on November 30th, with the drivers having a few days to do some training and reconnaissance laps around the track. The experience was valuable for some of the foreign drivers, mainly Uruguayans, as few international races had happened in Interlagos until then.

However, the first defining moment of the weekend would take place on Saturday, the 29th, when qualifying would take effect. The majority of drivers registered for the event participated in this session, which saw a beautiful duel between Brazilian and Argentinian drivers. In particular, the performance of Fritz d'Orey and Froilán González deserves to be highlighted, who continually exchanged the position of fastest driver on the circuit during this session. The Brazilian behaved magnificently, truly providing González with a challenge on par with his days as an international F1 driver.

Because of this, Fritz d'Orey had the upper hand at the end of the practice session, earning the right to start in the lead after a masterful lap on the Interlagos circuit, with a time of 3.42.5 – and which now became the absolute track record. González wasn't far behind in this contest, achieving the second-best time of the day with 3.47.4. Some of the other drivers who managed to set good times in the qualifying session were Nastromagario (3.56), Requejo (3.56), Iglesias (3.56.3), Danvilla (3.58.9) and Margarido (4.23.2).

On the other hand, drivers like Ciro Cayres and Asdrúbal Bayardo decided to skip the qualifying session, wanting to preserve their machines for the following day. This concern on the part of some drivers had very valid reasons, which proved to be concrete in some cases. For example, Oscar Mario González, who had been practicing regularly at the Interlagos circuit throughout the week, had a serious mechanical problem on the day of qualifying, forcing the driver to withdraw his entry just the day before the race.

Another consequence of the vehicle attrition rate could be seen the next day when minutes before the cars lined-up for the race, another of the drivers bidding for victory, Argentinian Jesús Iglesias, was also forced to give up participating in the event, due to a leak in his fuel tank. Argentinian mechanics tried their best to solve the problem, but Iglesias finally gave up after all attempts at a remedy failed.

And it was a close call that the event didn't lose another driver, as Asdrúbal Bayardo who had not participated in qualifying signalled on the day of the race that he was also suffering from a series of mechanical complications. However, with the help of Brazilian and Argentinian mechanics (who lent, in addition to their hands, parts from the ACA stock for emergency maintenance of the car), the Uruguayan managed to get his Maserati into trackworthy condition again, taking his position at the back of the grid.

Due to the various problems that plagued the teams in the days before the race, only 11 of the 16 entered cars took their starting positions that November afternoon. There would be 15 laps to be contested, with drivers from the 2500cc and 4500cc classes competing on the same circuit for the trophies of their respective categories.

When authorisation to start was given, both González and d'Orey jumped ahead, with the Ferraris competing wheel to wheel who would be the first in Turn 1. The Argentinian, using all the experience acquired in years of international motorsport, closed the Brazilian's space, forcing d'Orey to settle for second position. Behind, Cayres, Requejo, Danvilla and Nastromagario were in hot pursuit, hoping that the duel between the Argentinian and the Brazilian would create an opening for the lead.

However, such an option was not in the plans of either d’Orey or González, who presented a beautiful duel to the crowd in these first moments of the race. In turn 2, the Argentinian still maintained the lead, but in the great Retão of Interlagos, Fritz matched up with the Argentinian and executed a beautiful overtake, retaking the lead. Throughout the rest of the lap, d’Orey tried to gain an advantage in the lead, with González opting for the strategy of following the young Brazilian driver at a distance.

End of the first lap, and Fritz d’Orey was already a few seconds ahead of Froilán González who, in turn, had also separated himself from the pursuers. Ciro Cayres and Ramón Requejo remained in third and fourth positions, respectively, but Nastromagário had managed to overtake Danvilla for fifth place.

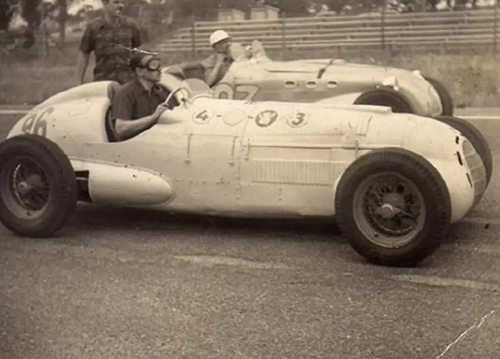

Ramón Requejo (inside) and Froilán González (outside) share the curve at Interlagos during the race held there in the 1958-'59 edition of the Triangular. (credits Luciano Cuevas)

The positions did not change on the next lap around, with the only difference in the field being the retirement of Franco Ciamarone due to mechanical problems – the driver was already among the last positions of the field, therefore his retirement did not substantially change the course of the race. However, on lap 4, the first significant casualties of the race occurred, the first being Ramón Requejo, who at that time was in fourth and abandoned the race due to a mechanical failure in his Requejo/Corvette.

The second blow would also come through mechanical problems, but these would be with Brazilian Ciro Cayres. The São Paulo native was another of the group of drivers who was plagued with mechanical problems throughout the weeken, and only by a miracle the Brazilian had managed to start with his Ferrari 195S on the 30th. So, Cayres did not have any reasons to be disappointed, because the low expectations were even exceeded. To be honest, it was a surprise that the car lasted more than a couple laps.

These issues promoted Paschoal Nastromagario to third, already far behind Froilán González and Fritz d’Orey. The Teuto-Brazilian seemed to not care about the large advantage he had already built over González and continued to set an extremely fast pace in the lead of the race. Despite the gap, the Argentinian did not seem to be worried with d'Orey's pace, remaining firm in his strategy of conservation and racing cadence.

Although it seems that González's more passive method was a big trap for his goals of winning the competition, in the end, the Argentinian's patience was well rewarded. Shortly after completing the seventh lap, Fritz d’Orey, while preparing to take turn 1, lost his right rear tyre after it burst. Although the driver controlled his vehicle well, avoiding any damage to the machine, d'Orey would now be forced to do a complete lap of the circuit on three wheels in order to replace the damaged tyre. It is worth remembering that at the time, the circuit was 7.960km long, much more than the 4.309km of today's Interlagos.

Because of this, d'Orey saw his skillfully built advantage completely destroyed as the driver slowly crawled down the track. The minutes of advantage that Fritz had over González at the start of lap 8 had turned into a disadvantage when the latter entered the pit. At the exit, Fritz had already dropped to fourth, behind not only Argentinian González but also behind Uruguayan Carlos Danvilla and compatriot Paschoal Nastromagário.

A gap of 2 minutes and 11 seconds now separated d'Orey from González and with nothing left to lose, the Brazilian once again began to set an extremely aggressive pace in the race. Until the end of the race, Fritz got the most out of his Ferrari equipped with a Corvette engine and despite not being able to overtake any of his rivals in front of him, the driver demonstrated why he was one of the biggest promises in Brazilian motorsport: adding to his record set the day before for the fastest lap in free sessions, Fritz had also managed to set the record in racing conditions, with a lap of 3.43.

But nothing the Brazilian could do would change the final outcome of the race, which seemed defined as soon as González took over control of the contest. The Argentinian remained impassive, definitively consolidating his position after the Brazilian's bad luck. Without being threatened by any of his other competitors in the following laps, José Froilan González crossed the finish line first, with a total time of 58.27.4 and thus winning the first points for a driver in the Triangular Tournament. A minute and a half behind, Danvilla crossed the line. He had defended until the final laps from Nastromagario's attacks, as the Brazilian driver was the final driver to take the podium at Interlagos.

Race 2: Premio Comisión Nacional de Turismo

Although 1958 had already given way to 1959 on the calendar, the first edition of the Triangular was still only on its second leg. Scheduled to take place on January 20, 1959, the race in Uruguay would be the first stop in the double weekend of races that would close the championship, with the event in Argentina being scheduled for the following Sunday (27).

The venue for the dispute would be the El Pinar circuit, located in the department of Canelones and approximately 30 kilometers east of Montevideo. The track was inaugurated in 1956 with two variants available for racing: the first layout encompassed a triangular-shaped outer ring, just over 2,200 metres long – and which was rarely used in international races. Variant number 2 added an internal section to the circuit, which substantially increased the lap length, to 2,700 meters. Despite this increase in the second layout, the track maintained the same characteristic in both variants: being an extremely fast circuit, with very low lap times compared to those of the first stage of the championship (Interlagos). Due to this, El Pinar was at the time one of the best attended circuits in South America, with a wide range of national and international events throughout the year.

So it was no surprise that the drivers called up to participate in the race felt comfortable with the choice of the circuit as one of the venues for the tournament. The teams entered by Brazil (Ciro Cayres, Fritz d'Orey and Paschoal Nastromagario) and Argentina (Froilán González, Jesús Iglesias and Ramón Requejo) remained the same as in the first stage, while Uruguay decided to change its line-up.: Mário González left, being replaced by the experienced Alberto Uria – however, the two other drivers from the Uruguayan team, Asdrúbal Bayardo and Carlos Danvilla, would continue as the representatives of the Colorados in the championship.

Despite the apparent confidence of the AUVO organizers in being able to hold the race on the scheduled date, plans suffered a major setback a few days before the official launching of the event. It all started when the Brazilian delegation left for Uruguay, the week before the El Pinar race. The boarding of cars, teams and drivers took place in an exemplary order, with the group being accommodated on the freighter 'Drina', of English origin, and which was destined for the busy port of Montevideo.

The delegation's peaceful trip was interrupted as soon as the Brazilians arrived in Uruguay, receiving information that a dockers' strike had paralysed all activities in the port area of Montevideo. Despite urgent requests from the AUVO, the ACU and the ACB begging for a short lift-off of the strike, with the aim of allowing the release and unloading of machines on an exceptional basis, the port workers were irreducible in their demands, stating that only if their requests were met by the Uruguayan government would they resume their activities.

The days went by, with a deadlock that had no end in sight. The Brazilian drivers, without their cars, took the opportunity to get to know the Uruguayan capital, and, as the weekend of the race approached, they headed towards El Pinar in the hope that by some miracle their vehicles would arrive in time to participate in the contest. However, luck really wasn't on the Brazilians' side that weekend and it was clear that when the first free practice sessions began to unfold in El Pinar, time had finally run out. No driver from the Brazilian representation would compete in the race.

But it was already too late to cancel the event, as the Uruguayan and Argentinian drivers were already nestled in the circuit's pits. In a very conscious manoeuvre by AUVO, it therefore decided to transform this event into the first stage of the Uruguayan championship of Fuerza Libre, which was scheduled to start just a few weeks later. Consequently, to the relief of the Brazilian drivers, the race was disqualified as an event belonging to the Triangular, the event postponed indefinitely until the situation in the port of Montevideo was resolved.

It would take a month for the tensions in the port to calm down, so that the second stage of the South American Triangular could finally be officially held. The Brazilian drivers returned to Uruguay again at the end of February 1959 and, this time, no problems affected the disembarkation of the Tupiniquim delegation. The same dockworkers who had previously been so hostile to the requests of the ACB and AUVO in January, were now extremely kind and supportive to the Brazilian drivers.

The main problem that had affected the organisation of the tournament with this delay had not even been the issue of time, which was handled well by the Triangular representatives – the date chosen for scheduling the event was by mutual agreement defined by Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina, affecting none of national automobile calendars of each country. The most worrying issue was of a financial nature, since the costs of organising a second race in El Pinar, coupled with the expenses already incurred for the useless hosting of Brazilian drivers and teams in the January race, had proven to be too costly for the AUVO's lean budget. Due to this delicate situation, the institution had to look for partners in the private sector to be able to promote the second stage of the season. Luckily, there was no shortage of people interested in sponsoring the event, given the possibility of international visibility that such race could provide to those interested.

Once again, the teams designated by Brazil and Argentina remained unchanged, with the only difference being that promoted by the Uruguayan delegation, Oscar Mario González and his Ferrari 375/Corvette were reinstated to the AUVO team, with Alberto Uria losing his spot in the squad.

A rare image of the Bugatti Grand Prix car of Uruguayan driver Trabal Cortés. Little is known about this car, with the strongest hypothesis being that the vehicle was built over a Type 35 or Type 37 chassis. (credits Rafael Bastida)

The drivers met at the El Pinar circuit again on February 20th, when some open track sessions were made available for the teams to test the proper functioning of their machines. However, since many of the drivers chose to skip this type of session, to preserve their cars as much as possible for the decisive moments of the weekend, few ventured onto the 2,700m circuit that Friday.

On Saturday, the situation would be quite different. The qualifying sessions proved to be well contested, especially by the Argentinian and Uruguayan drivers, who had competed in the Fuerza Libre race on the site a month earlier. Unfortunately for the Brazilians, Cayres, d'Orey and Nastromagario were content to set decent times, but which were below their South American rivals. For example, the best in this group would be Ciro Cayres, who would start from fifth position in his Ferrari/Corvette.

In front of him, an intense confrontation for the top positions developed between Uruguayan Carlos Danvilla and the Argentine squad of Requejo, Iglesias and González. And, despite all odds, it would be Danvilla who would be the best in the group, finishing at the top of the timesheets of the day, with a time of 1.20.6. The crowd went wild with the lap that gave Danvilla first place; but also, it breathed a sigh of relief after the tense session. Simply because it was mere a one second that separated the Uruguayan from fourth-placed Froilán González at the end of the classification. Iglesias was second, just seven tenths slower than Danvilla, while Requejo was also (like González) one second behind the Uruguayan.

With the 20th looming on the horizon, it was finally time for the second leg of the South American Triangular. 14 cars lined up at the El Pinar circuit, with the grid order being as follows: 1st C. Danvilla (Ferrari 500/Corvette); 2nd J. Iglesias (Pian/Chevrolet); 3rd R. Requejo (Requejo/Corvette); 4th Froilán González (Ferrari 625/Corvette); 5º C. Cayres (Ferrari 195s/Corvette); 6º F. d'Orey (Ferrari 275/Corvette); 7th P. Nastromagario (Ferrari 195S/Corvette); 8th J. Fernández (Fernandez/Chevrolet); 9th O. González (Ferrari 375/Corvette); 10th T. Cortez (Bugatti GP); 11º H. Fojo (Maserati 4CLT-48/Corvette); 12th M. Galván (Galván/Thunderbird); 13th A. Bayardo (Maserati 4CLT-48/Corvette); and 14th R. Bonomi (Maserati 300S).

More than 20,000 people witnessed when the flag was dropped, and the cars accelerated for the first of 50 laps valid for the GP. Ramón Requejo jumped into the lead, followed by Jesús Iglesias and Brazilian Ciro Cayres. Carlos Danvilla had a terrible start, losing several positions and settling only in the middle of the field. Froilán González opted for a safe start, remaining in fourth position in the early moments of the race.

However, this was just another one of González's conscious strategies, who after the chaotic moments of the start was already preparing to attack his rivals. And it didn't take long for them to make way for 'El Toro de los Pampas', with Froilán overtaking both Cayres and Iglesias by the end of the second lap. Now González's sights were set on Requejo, who maintained a tenuous lead in the race.

Further back, other clashes were also taking place, the most interesting of which was for fifth position: the cars of Oscar Mario González, Marcos Galván and Fritz d'Orey were separated by just a few metres throughout the entire initial stage of the race, with the Uruguayan standing firm in his position, without giving up a single inch of ground to his pursuers.

Returning to the lead, a change occurred on lap 3, as Froilán González now dictated the pace of the race, with Ramón Requejo dropping to second position. Froilán set an extremely imposing rhythm in the lead, and it didn't take long for Requejo to lose contact with his compatriot. Even so, Ramón had bigger problems to worry about, as Iglesias and Cayres were quickly closing in. It didn't take long for the three drivers to form a small peloton, which would later be joined by Mario González and Marcos Galván. Fritz d'Orey, who could also have joined this confrontation if it wasn't for a spin – the driver lost several seconds when trying to return to the track. The first casualty of this group occurred on lap 7, when Jesús Iglesias, who was in fourth place, had a piston failure, forcing him to abandon the race.

On lap 8, another change, as Oscar Mario Gonzalez managed to overtake Ciro Cayres for third. And the Uruguayan didn't stop there, unleashing a precise attack on Argentine driver Requejo on lap 10. In less than three laps, González had risen from fourth to second, in a sequence of beautiful overtaking moves that electrified the Uruguayan crowd.

In the following laps, Froilán González tried to increase the gap, which was close to 25 seconds at the 15-lap mark. Despite the Argentinian's spectacular performance, all eyes were on his Uruguayan namesake, who now faced a strong threat from Marcos Galván, who had overtaken Ramón Requejo on lap 14. From then on, Osmar González and Marcos Galván tried to turn this confrontation into something personal, with the pair rarely being more than a few metres apart. Requejo remained on the sidelines, while Ciro Cayres was already a touch behind in the dispute, being harassed by Carlos Danvilla.

The plot of the race remained the same during the next 10 laps, with the only variation being some ephemeral approximation by Requejo of the O. González vs M. Galván skirmish. However, at the end of lap 26, the crowd was on its heels again, as Galván overtook O. González right in front of the main grandstand at the El Pinar track. However, the Uruguayan would not let himself be beaten that easily, and less than four laps later, González regained second position.

The race of attrition unfolding between González and Galván began to have its side effects, as it allowed Requejo to close in. The Argentinian, who had watched the duel from a distance, saw a window of opportunity to move up a few positions and, little by little, began to close the gap between himself and his opponents ahead. The result of Requejo's attitude was that the Argentinian was in striking range of Marcos Galván and Oscar González on lap 31. On the next lap, Requejo was already overtaking the Galvan/Thunderbird while on lap 33, González's Ferrari was the next to fall victim to Requejo's offensive. While the Argentinian took second place, Froilán González already enjoyed a huge advantage in the lead, which was by now nearing a full minute.

Despite this huge disadvantage, Requejo demanded everything from his car, trying to shorten the distance that separated him from the lead. Even with Requejo consistently turning faster laps than González, the time the driver discounted per lap was not enough to bring Requejo even close to Froilán González – the laps were disappearing from the counter and, with them, Requejo's hope of getting his first victory in the championship. Once again, a dominant performance from Froilán González would guarantee him the laurels of victory, crossing the finish line comfortably in first place.

Requejo, in the 15 laps he had to get close to González, had managed to reduce his advantage by almost a half, from 55 seconds to 23. Even though he had to settle for second place, Requejo deserved great praise for his commitment and determination to reach Froilan González by all means. Adding to the top three, Oscar Mario González, who after the long confrontation with Galván managed to distance himself from his compatriot in the final laps, secured a well-deserved place on the podium.

Race 3: XV Gran Premio Ciudad de Buenos Aires

Leaving no opportunity to chance, less than a week later the main Brazilian, Argentinian and Uruguayan drivers were already en route to Argentina's capital to compete in the final round of the 1958-'59 Triangular Tournament. The championship would end at the traditional Gran Premio Ciudad de Buenos Aires that after years as a recurring stop for the F1 circus had resumed its more regionalised character.

This was mainly due to the problem of the ACA with finding sponsors interested in investing resources in the race, which had lost much of its intercontinental appeal after the progressive retirement of drivers from the golden generation of Argentine motorsport in the 1950s. Therefore, without funds and without great public interest, the maximum the institution could do to keep the event at a minimally international status was to include it as part of the Triangular Tournament.

Despite this apparent downgrade in nature, the 15th edition of the GP in the Porteña capital promised to be a spectacle on par with that of its Formula 1 days. An impressive line-up of 24 drivers had been released to the press days before the race, showing how the decision of the ACA would give a decent continuity to the heritage of the national GP. The teams representing Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina had the same trios that had been representing these countries since the beginning of the championship, with the remaining spots being filled by numerous Argentine drivers, coming from the national Fuerza Libre.

Even with the championship title decided in favour of Froilán González (as the two victories in the two round contested so far gave the driver a score that could not be matched by any of his rivals) this did not prevent the drivers present from strongly aiming to win at Buenos Aires. Especially ambitious were the Argentine Fuerza Libre drivers who after years of watching this race from the grandstands (since competing in the Buenos Aires GP in its F1 years was an opportunity available to a few selected drivers) would now have the chance to compete in such a mythical and renowned South American event.

Activities at the Buenos Aires circuit began on Saturday, February 28th, when the qualifying session began. There were few drivers who wanted to spare their machines and, as a result, cases of drivers who exceeded the limit that their vehicles were not rare. For example, Asdrúbal Bayardo, while trying to achieve fastest time of the day broke the clutch on his Maserati. Without time or spare parts, the driver was forced to leave the Uruguayan delegation even before the day of the race, now placing the weight of the celestial flag on the shoulders of Carlos Danvilla and Oscar Mario González. However, this would not be an isolated case, with another half-dozen vehicles experiencing terminal mechanical problems in the practice session.

While some had problems, others avoided the inconveniences. After their disappointing participation in the Uruguayan leg, the Brazilians wanted to redeem themselves in front of their hermanos. Fritz d'Orey and Ciro Cayres fought a beautiful duel for second position on the starting grid, with the small audience present during qualifying paying close attention to each new time set by one or the other driver. In the end, it was d'Orey's more modern Ferrari that performed better, achieving second-best time of the day with 1.52.7. Cayres was right behind, in third place and just half a second slower than his compatriot.

However, none of the Brazilians' efforts came close to the mark set by Froilán González during the qualifying session. The Ferrari 625 equipped with a Corvette engine seemed once again to be in total harmony with its master, and its time of 1.47.3 seemed to be the biggest exclamation point in this sentence. No one tried to dislodge González from the top, with the lap becoming the absolute Fuerza Libre record on the Buenos Aires circuit.

However, the best time in practice was the least of Froilán's ambitions, as he saw the very real possibility of sweeping the Triangular Tournament in its first edition. Added to this was the fact that Froilán had only once won the Buenos Aires GP, back in the distant year of 1951 when the race was still valid as a stage of the Argentine Temporada. However, this victory was achieved when the race was held on the Costanera street circuit; therefore, this was the driver's chance to have victories in the two places where the GP had been held in its history (as an observation, the only ones who had achieved this feat until then were the Italians Villoresi and Ascari). But before this could happen, 'El Toro de los Pampas' would have to overcome the 17 opponents and 60 laps that stood between him and his dream of winning the trophy on the Autódromo Municipal Ciudad de Buenos Aires.

Fritz d'Orey (#4) and Jesús Iglesias (#3) try to overtake backmarker Kurt Delfosse (#11)

in the Argentine leg of the 1958-'59 Triangular. (credits Luik Racing)

The story didn't start well for González on that 1st March of 1959. As soon as the start authorisation was given, Brazilian Fritz d'Orey took the lead, followed by Carlos Danvilla and Ramón Requejo. Froilán fell down several positions and found himself stuck in fourth, followed promptly by Jesús Iglesias, Ciro Cayres and Oscar González.

However, the Argentinian and his Ferrari 625 didn't take long to produce a reaction, and before the end of the first lap Froilán was leading, two seconds ahead of d'Orey and Danvilla. Ramón Requejo had fallen from third to sixth position, while Iglesias and Cayres were fighting over fifth. On the next lap, F. González's advantage became even more elastic, with Fritz d'Orey and Carlos Danvilla opening their laps 12 seconds in arrears of the Argentinian. On lap 3, Froilán and his Ferrari were even further away, with a 16.5-second advantage over their main pursuers.

At this moment, there was a small change in the group of drivers who were trying to maintain contact with González: while Fritz d'Orey continued in hot pursuit, Carlos Danvilla was replaced by Jesús Iglesias (who had made a series of overtakes in the previous laps, recovering important positions in the fight for the front pack of the race). The Uruguayan experienced problems with the mechanical part of the car since the first moments of the contest, and, on lap 6 he was forced to effectively abandon the race, after a broken oil pump in his Ferrari.

Mechanical issues also explain the reason why another driver who started well in the race disappeared after five laps, as Ramón Requejo experienced constant engine misfires. Breaking a piston on lap 7 sealed the Argentinian driver's fate: a tour to the pits and later the Requejo team garage.

These retirements allowed some lesser-known drivers on the international scene to surface, as on lap 8. Roberto Bonomi (Maserati 300S) and Alberto Rodriguez 'Larry' Larreta (Alfa Romeo 308C) found themselves in fifth and sixth, only ten seconds away from third-placed Iglesias. Returning to the front, Froilán González enjoyed an advantage of more than 37 seconds over now second-placed Jesús Iglesias, who had finally managed to overtake d’Orey. Ciro Cayres now found himself in a skirmish with Bonomi for fourth place, while Larretta was left behind in this dispute.

On lap 12, Rodriguez Larreta was another to retire from the race, due to serious issues in the braking system of his Alfa. While one Argentinian headed towards the pits, another shone in the race: Roberto Bonomi, who between laps 11 and 15 jumped from fifth to second in a spectacular demonstration of strength by the Maserati sportscar against its leaner Fuerza Libre rivals.

In the following laps, some other changes gradually altered the face of the front group while Froilán González remained firmly in first position with an average advantage of one minute over second-placed driver Bonomi. Fritz d'Orey was back up in third place after Jesús Iglesias was forced to make an unexpected pitstop, dropping the Argentinian back to fifth place. However, Iglesias would not stay in that position for long, being promoted to fourth when Ciro Cayres also had to take an unexpected pitstop.

Froilán González (far right) and Fritz d'Orey (middle) jump ahead during the start

of the XV Gran Premio Ciudad de Buenos Aires. (credits unknown)

At the 25-lap mark, the order of the top five was: 1st José Froilán González (Ferrari 625/Corvette); 2nd Roberto Bonomi (Maserati 300s); 3rd Fritz d'Orey (Ferrari 375/Corvette); 4th Jesús Iglesias (Pian/Chevrolet); 5th Osmar González (Ferrari 375/Corvette). In addition to these five drivers, only four others were still on track when the race reached its halfway point. The contest remained in a stalemate for most of the following laps, with Froilan González providing the only moments of entertainment for the crowd every time he overtook one of the backmarkers on the track. The one spared by González was Bonomi, who held on as the last driver on the lead lap at the start of lap 40.

However, these moments of tranquility were replaced by those of anguish on lap 43. While Froilán González's triumph at Buenos Aires seemed assured, with the Argentinian a sea away from his closest pursuer, González's Ferrari rattled and coughed in front of the main grandstand of the circuit. Slowly the car moved to the side of the track until it came to a complete stop. The Ferrari's differential had broken: it was the end of González's dream of sweeping the championship with a victory on home soil – but nothing was all that bad, since as a consolation prize González would still win the Triangular champion's trophy.

The retirement of González promoted the surprising Bonomi into the lead which proved to be as fleeting as the blink of an eye. In less than a lap, Roberto Bonomi also retired from the race due to clutch problems. The problem was not very serious (a connector cable had broken) and a quick repair would bring Bonomi back into contention – an act that the Argentinian's team executed quickly, with the Maserati back in racing condition only a few minutes later. However, luck really wasn't on Bonomi's side, because when he was accelerating in the pits to return to the race, his engine stalled! Another wasted leadership in Buenos Aires.

Therefore, with 15 laps to go, it was Brazilian Fritz d'Orey who topped the charts, followed by Jesús Iglesias and Osmar González. At this point, the Buenos Aires race had become a survival contest, as only Luis Milán (Ferrari 375 Plus), Hector Rey (Rey/Chrysler) and Kurt Delfosse (Gordini T15/Porsche) also remained in the race.

Fritz and Iglesias were the drivers to provide the final emotions in the race. The Argentinian was pushing the pace in an attempt to shorten a gap that was close to 30 seconds with 12 laps remaining. Despite Iglesias's obstinate efforts, only a stroke of luck would hand the Argentinian victory in his national GP. It finally came, on lap 50, when the radiator of d'Orey's Ferrari ruptured, seriously damaging the engine of the Brazilian's machine.

Jesús Iglesias easily passed Fritz's faltering car, with the Argentinian now content to complete the final laps of the race at cruising pace. With no threat in sight, Iglesias crossed the finish line for the 60th time with a total time of 1.58.52.3, sending the Porteño crowd into a delirium as they watched their local hero achieve victory in the XV GP of Buenos Aires. Almost half a minute behind was second-placed Osmar González in a very safe and conservative race made by the Uruguayan. Luis Milán, third on the podium, could also boast a very strategic race, as he had hoped that problems hitting his opponents would generate a good result at the end. As it turned out, results were even better than those originally imagined by the Ferrari 375's owner!