The Argentinian F3 Temporada of 1967

Time to go south again!

Author

- Lorenzo Baer

Date

- May 10, 2024

Related articles

- 1949 Brazilian Temporada - Brazil's forgotten racing days, by Lorenzo Baer

- The 1960-1975 South African Drivers Championships - Grand Prix at the Cape, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas/Rob Young

- 1966 Argentinian F3 Temporada - It's never too late to revive old passions, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1968 Argentinian F2 Temporada - The quick dash of the Cavallino Rampante in the Argentinian Pampas, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1969 Tasman Championship - Something that Chris Amon did win, by Tom Prankerd

- 1970-1975 Tasman Championship - Back to Pukehoke for a revival of F5000 Tasman days, by Gareth Evans

- 1971 Colombian F2 Temporada - When Formula cars roared in the Coffee Land, by Lorenzo Baer

- Cuba, Bahamas, Puerto Rico - Racing Juniors in the tropics, by Lorenzo Baer

Who?Jean-Pierre Beltoise What?Matra MS5 Where?Buenos Aires When?1967 Gran Premio Ciudad de Buenos Aires Nafta 'Super' YPF |

|

Why?

After the good impression left by the 1966 International Temporada, it is not surprising that there was almost an outcry from the Argentine authorities and public for the event to be held again in 1967. In yet another logistics lesson demonstrated by the authorities in Buenos Aires, in just a few months the story of another Formula championship in the southern hemisphere began to take shape; one that would be marked by dramatic moments, like those that would happen in the second round of the season, at Mar del Plata.

But also, spectacular ones like the memorable displays the Matra squad would provide to the public. The 1967 Argentine Temporada demonstrated that even with the promptness of everyone involved some things always can go wrong, making it necessary to admit mistakes so that you can continue moving forward. The technological progress of motorsport was unstoppable, and race organisers needed to be aware of this in order to conciliate the safety of the circuits, the public's interest and the greater speed of the machines.

A difficult balance to achieve, but not entirely impossible. The truth is that the 1967 Temporada would stretch the ACA's efforts and resources to the maximum, which, already thinking about the next editions of the event, saw that it was necessary to evolve in some way, leaving behind any residue of amateurism that still permeated the institution. Therefore, if 1966 was the testing year for a redesigned idea of the Temporada, 1967 would be the year in which the concept matured; and also, a year of great learning.

Getting back on track: the first steps of the 1967 Temporada

Despite having been confirmed during the course of 1966, it was only at the end of that year that the first general outlines of the 1967 Temporada began to become public. The first major sign that the event was underway was the trip of representatives from the Automóvil Club Argentino (ACA) to Europe, in November, to survey those interested in participating in the series on Argentine soil.

In addition to establishing this first contact, the main mission of the ACA commission was to return to Argentina with some positive nods, which would guarantee at least some international attraction to the races. The final result was very positive for the commission, given the difficulty in negotiating agreements with Formula 3 teams, due to the budget caps they faced.

The first great signing for the 1967 Temporada was Matra Sports, which after its first experience in Formula 3 in 1965 had gained volume and respect from its rivals throughout 1966, only to transform, towards the end of that year, into the most professional F3 team on European grids. But not only the French accepted the invitation, as the English Ron Harris Racing Division and the Italian Scuderia Madunina also nodded positively to the ACA invitation.

In addition to these, some old faces from the 1966 edition would return to the lands south of the equator: Goodwin Racing (through Lythgoe-Goodwin Racing) and Martinelli + Sonvico Racing Team, which would join some privateers and independents who also signed agreements with the Argentine representation during its stay in Europe.

Once again, Argentina became the home for Formula 3 during the months of January and February.

(credits Historia del Autodromo de Buenos Aires)

The second reason for the trip of the members of the Automóvil Club Argentino to Europe was the purchase of new F3 vehicles for the ACA, as the institution had announced the restructuring of its own single-seater team, which had been abandoned for years and was, until now, in the second plan of Argentine authorities.

The ACA team had risen to prominence in the early 1950s, after revealing and sponsoring most of the popular Argentine drivers of the time (such as Juan Manuel Fangio, Froilan Gonzalez and Óscar Galvéz). The team was maintained through a scheme of financing new talents or recruiting the great Argentine stars of world motorsport, when they came home to compete in the Argentine F. Libre Temporadas.

This scheme lasted more or less until the end of the 1950s, when the last drivers from the forties and fifties class of the ACA retired from racing (a time that also coincided with the removal of the Argentine GP from the Formula 1 calendar). Due to the loss of global appeal, the ACA sought to focus on the national scene, through the Fuerza Libre, Fuerza Limitada and later, Formula 1 Mecánica Argentina championships. Only with the 1967 Temporada did the team have a new opportunity to reaffirm itself in an international context.

While such events were developing in Europe, in Argentina, the ACA was also moving, seeking to solve one of the biggest problems that always affect event organisers anywhere in the world: the discussion to establish the venues for an international series.

After a few months of preparation by the ACA, characters and cars are finally presented to the public in Buenos Aires. (credits Automundo)

The only certainty at the beginning of the survey work was that Buenos Aires would continue to be the epicentre of the Temporada, with the premiere taking place at the Autódromo Municipal. But after this event, a total overhaul of the calendar had been carried out for 1967: both Rosário and Mendoza were dropped from the schedule, due to logistical problems and inadequacy of space for carrying out new events. Mar del Plata, which had been the stage for the last leg of the 1966 Temporada, would be promoted to act as the second round, taking advantage of the resort's peak tourism season, at the end of January.

To complement the rest of the calendar, Córdoba and a second race in Buenos Aires became the strongest contenders for the vacant legs. What played in favour of the first was that Córdoba was (and still is) the second largest city in Argentina, in addition to having a large industrial complex, mainly in the automotive segment – which made an obvious connection with a Formula 3 race.

In the case of Buenos Aires, the race track in that location continued to prove itself as the most adapted to host large-scale automobile events in the country. Therefore, if the objective of the Temporada was to reinforce an image of organisation, hospitality towards foreign guests and on-track competitiveness, why not make the most of the best race venue available in Argentina?

In this way, it was decided that Buenos Aires would host the opening and closing rounds of the championship, with Mar del Plata and Córdoba sandwiched between both events held in the Argentine capital.

Drivers and teams

As mentioned, the main attraction of the 1967 Temporada was Matra Sports, which would take the trio formed by Jean-Pierre Beltoise, Jean-Pierre Jaussaud and Johnny Servoz-Gavin to the pampas. Henri Pescarolo, who was the main driver of the French team at the time, would be absent due to personal reasons.

Because of this, Beltoise had been promoted to the role of team leader in Argentina, due to his good appearances in Matra's Formula 2 cars. If only the results of the European F3 in 1966 were taken into account, the leadership should have been given to Servoz-Gavin, who had won the French national championship in the category (the Championnat de France) with the Champagne-sur-Seine-based team.

It was up to the trio of drivers to execute the plan that became known as Operación Argentina. In this planning, it was stipulated that the Matra Sports board would deem the trip to the south of the equator as positive only if the team managed to 'sweep' the championship, winning all four valid rounds of the 1967 Temporada. No failure would be admitted, as to prove that Matra cars would be the machines to be feared in Formula 3 in the season that was about to begin.

However, since the Argentine Temporada took place between January and February, Matra did not have time to modify its chassis to the new specifications for the 1967 season. Therefore, instead of the drivers having the 'new' MS6 (which was basically the 1966 MS5 with updates to the suspension system) the trio would have to use practically the same cars as raced at the end of 1966.

The Operación Argentina became Matra's main objective at the beginning of 1967. Not surprisingly, three of the team's drivers were sent to the land of tango, with Jean-Pierre Beltoise leading the group. (credits unknown)

The main threats to the French squad came from the English Ron Harris Racing Division and Lythgoe-Goodwin Racing. The first, founded by British film distributor Ron Harris, gained fame during the mid-1960s, mainly in Formula 2, as it was considered the official representative of the Lotus team in that category, with a 'semi-works' team status. Despite the fame generated by the F2 project, Ron Harris also had a sub-division dedicated to Formula 3, which also used the British manufacturer's cars.

By the time of the race in Argentina, the Ron Harris Racing Division had already ended its involvement with Team Lotus and had transformed itself into an independent. Therefore, it was a courageous decision to send three drivers to represent the team's colours overseas: British driver John Cardwell, who had raced in the 1966 Argentine Temporada, returned to Buenos Aires to try his chances once again. The driver had exchanged his position at Goodwin Racing for Ron Harris shortly after the end of the '66 Temporada, aiming to have a more competitive machine compared to his rivals.

Another one who was looking to remember his strong performances in Argentina was Eric Offenstadt who this time would not race as a privateer. After the impression left by the driver after the 1966 F3 International Temporada, Offenstadt was hired by the works Pygmée team, to compete in the French and Italian Formula 3 championships, and at the same time the driver still competed in Formula 2 races as a privateer or for Stephen Conland Motor Racing. This arrangement lasted until September 1966, when the driver signed an exclusive contract with Ron Harris.

The third member of the team was the Italian Giacomo Russo (known as 'Geki'), who had extensive experience in single-seaters – including being the 1964 Italian F3 champion – and touring cars. The curious story is that despite not being an official team driver, this was not 'Geki's first time aboard a Ron Harris cockpit.

In August 1966, the driver drove a team car in a round of the Italian Formula 3 championship at Enna-Pergusa. This one-off with Ron Harris was part of an agreement that involved the Italian driver and his preparation to drive one of the Lotus official cars in the 1966 Italian F1 GP. Since 'Geki' had spent the last few years driving mostly Wainers and De Sanctis, the driver realised that if he wanted to drive the British car well, he needed to at least have a superficial knowledge of a Lotus car – and the simplest solution was the involvement of Ron Harris and its Lotus F3.

For the Temporada, two types of vehicle models would be lined up by the team: for Offenstadt a Lotus 35, which was an older type from the British constructor (manufactured in 1965), but which still held its value. However, for Cardwell and 'Geki', two Lotus 41s were assigned, these being more advanced models that had been introduced in the European spring of 1966. The type 41 was basically a new design with substantial mechanical improvements compared to the type 35. Despite the differences, all three vehicles were equipped with the same 997cc Ford 105E engine tuned by English firm Holbay.

Against Ron Harris' three-pronged effort, the Lythgoe-Goodwin Racing would respond in the same tone and scale. Originally formed by the partnership of brothers Natalie and Hugh Goodwin, the team basically embodied the myth of European single-seater motorsport during the 1960s: the Goodwin brothers' cars circulated around Europe looking for any race they could compete in. England, France, Belgium, Italy and even Spain were some of the countries in which the team competed in F3.

The team had also competed in the 1966 F3 Argentina Temporada and, when a new invitation arrived for the 1967 edition, Natalie and Hugh did not refuse it. The only problem was the cost of the trip which, as they already knew from their previous experience in 1966, was much higher than that of a gypsy life in Europe. However, it didn't take long for Goodwin to find an interested partner, which materialised in the shape of Frank Lythgoe Racing, an established British F3 team.

The partnership established Lythgoe-Goodwin Racing which divided its responsibilities as follows: Frank Lythgoe Racing supplied a Brabham BT18 to Alan Rollinson, while Goodwin Racing was responsible for Natalie Goodwin's (who at the time was already an experienced driver in single-seater racing) own BT18 and the BT21 of Charles Crichton-Stuart, the champion of the 1966 Argentine F3 Temporada.

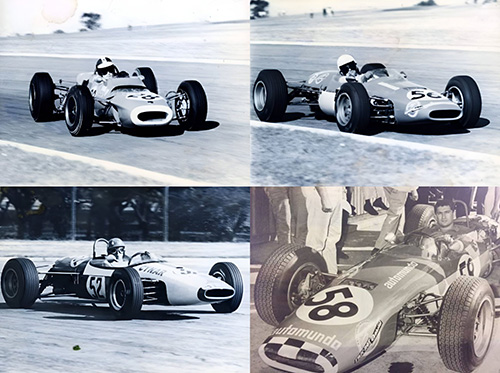

Some of the characters from the 1967 Temporada_ above, left, Jean-Pierre Beltoise (#28), above, right Carlos Pairetti (#56), below, left, Silvio Moser (#52): below, on the right, Juan Manuel Bordeu (#58).

(credits Alejandro de Brito and others)

Another major highlight of the 1967 edition of the Temporada was the traditional Scuderia Madunina, which entered no less than seven Italian drivers in the championship, on the most diverse machines available. The brothers Carlo and Rosadele Facetti, in addition to Alfredo Simoni, would each drive a Tecno TF/66, Giovanni Alberti, Antonio Maglione and Romano Perdomi (known as 'Tiger') would each drive a De Sanctis, and Giancarlo Baghetti would drive a Lotus 41.

Scuderia Madunina was founded by Marcello Giambertone, better known as a friend and agent of Juan Manuel Fangio, at some point in the mid-1950s. Besides being an official and established team, the Scuderia Madunina had a second source of income, providing services to other drivers who wanted to participate in motorsport events. For example, if a driver had the means to buy a single-seater but could not form a team around it, he could hire the services of Madunina, which would provide him with mechanics, timekeepers and other members of a motorsport team.

While Alberti, Maglione, Perdomi and Baghetti were part of the 'proper' Scuderia Madunina, a special addendum must be made to the drivers with Tecno cars. Despite being registered by Giambertone's team and sharing the same facilities, the cars basically constituted a separate team, as the trio of Carlo, Rosadele and Simoni was 'kind of' an official effort by the factory Tecno team.

There are a few plausible reasons to explain why the cars were entered by Madunina and not by Tecno: the first was that the Italian constructor had little experience in the F3 scene, having contested no more than a handful of races in 1966, in addition to the fact that until the construction of the TF/66, Tecno was specialised solely in building karts. In this way, the team sought a strong ally in the automobile scene, and in this case, that was Madunina. Another possible explanation was the organisational know-how that Madunina already possessed at the time, given that Tecno had been a team made up of only two cars until now. Expanding to three chassis was a huge step – one that the team was not prepared to take alone.

So, this partly explains the great diversity of cars and drivers that the team took to Argentina in mid-1967. The other side of the coin that explains the large number of drivers that the team managed to add for the Temporada was that Madunina had a strong presence in Latin America, having helped to promote several GPs in the region (such as those in Cuba and Venezuela).

Charles Crichton-Stuart, in one of the Lythgoe-Goodwin Racing Brabhams. (credits Raul Manrupe)

The Swiss contingent that would once again attend the Temporada was represented by two teams: Martinelli + Sonvico Racing Team, which returned after its first experience in the 1966 Argentine Temporada, with the duo formed by Clay Regazzoni (Brabham BT15) and Silvio Moser (Brabham BT18), and the Zürich Auto Racing Partnership, which would count on the services of Jürg Dubler (Brabham BT18), whose great highlight in 1966 was the victory in the Portuguese GP.

From among the Argentinians, the biggest attractions would come from the teams of the Automóvil Club Argentino and the Escuderia Automondo. The first had spared no effort for this edition of the championship, seeking to recruit the best local talents to represent their colours. Well-known Argentine driver Nasif Estéfano would lead a group that would also consist of Jorge Cupeiro, Jorge Kissling, Eduardo Copello, Carlos Martin and Alberto Rodriguez 'Larry' Larreta.

Most of the drivers would be driving Brabham cars (BT15 and BT18 types) with the exceptions being Jorge Kissling and Nasif Estéfano. The first would drive a BWA, equipped with a Cosworth engine and Hewland gearbox. This car was originally purchased by the ACA team, intending to use it as the team's practice machine in which all drivers were required to drive a minimum number of laps before they were considered qualified enough to try out their new F3s. Due to the greater number of available drivers than cars, the BWA ended up being designated as the official machine of Kissling, who was the Argentine Formula 4 champion in 1966.

In the case of Nasif Estéfano, he also had a surprise under his sleeve regarding vehicles. The ACA, on its trip to Europe, had managed to negotiate a purchase agreement for a Lotus 41, which was considered the best customer chassis available for Formula 3 at the time. Due to the long years of service provided by Estéfano and his vast experience in Latin American motorsport, he was presented with the opportunity to drive the car during the championship.

Escuderia Automundo, which had formed the largest Argentine representation in 1966, had shrunk for the 1967 edition. Of its six original cars, only three remained under the auspices of the team sponsored by the Argentine automotive newspaper: Carlos Pairetti (Brabham BT18), Carlos Marincovich (Brabham BT18) and Juan Manuel Bordeu (BT15). Despite this reduction, the team brought great news to 1967: Juan Manuel Fangio had become president emeritus of Escuderia Automundo, contributing with his knowledge and influence to enable the team to reach new heights in the upcoming championship.

Filling the vacuum of the bigger teams, was Frank Manning Racing, which had deployed only one Cooper T83 to the southern hemisphere, a car that would be driven by Chris Lambert. Completing the numbers in the field were German Manfred Mohr (Brabham BT15) and Argentinians Andrea Vianini (Brabham BT21) and Eduardo Casa (Brabham BT15) who would race as privateers throughout the championship.

1. Gran Premio Ciudad de Buenos Aires Nafta 'Super' YPF (Buenos Aires, variant nº 2)

The first international stars began arriving the week before the first race in the Argentine capital. The Matra Sports squad was the one that made the biggest impression upon its arrival, as it took to the southern hemisphere a structure similar to that the team had used in the 1966 European races: a contingent of mechanics and managers who sought to get rid of the Argentine customs bureaucracy as quickly as possible.

The first day of open track for the drivers was on Wednesday the 18th. The Argentinians were the ones who opened the activities, seeking to reduce the advantage that the Europeans had in terms of intimacy with their machines. Italo-Argentine Vianini had the honour of the first lap completed in the 1967 Argentine Temporada, tackling the very uneven surface of the Autodromo Municipal.

Then came the drivers from the ACA team, all doing their regular laps in the BWA-Cosworth: Estéfano, Martin and Cupeiro didn't get along well with the clumsy machine, gladly accepting the opportunity to finally get their hands on their official cars. However, Kissling and Copello, who were used to driving more 'raw' cars (such as those in the Argentine F4 and Turismo Carretera categories) had fewer problems with the BWA.

Of the Europeans, few tried their luck on the first day in Buenos Aires: Jean-Pierre Jassaud was the only Matra representative present, while the trio from Lythgoe-Goodwin Racing did just a few laps before withdrawing from the circuit. In the end, it was Jassaud himself who was the fastest of the day, with a time of 1.42 – despite several complaints from the French driver about the quality of the circuit's surface. .

For the following day, another free practice session was on the calendar; and, once again, the Argentinians wasted no time to get on the track. Eduardo Copello was first, increasingly getting on top of the BWA, with Nasif Estéfano and Carlos Marincovich following the first driver's lead. Estéfano didn't stay on the track for long, due to problems with the Lotus 41's gearbox. His place on the track was taken by the Italians Giovanni Alberti and Giacomo Russo. The first seemed to be well below his compatriot, with ‘Geki’ only tenths of a second behind the best times of Estéfano and Jassaud set the day before.

But this difference would increase after Estéfano returned to the track a few minutes later. The Argentinian didn't even look like he was in free practice, lowering his mark on the track more and more. The 1.43 from the previous day had already become a 1.41 and before noon even arrived, the driver had already set a new record for variant no. 2 of the Buenos Aires Circuit: 1.40.2!

Activities slowed down during lunchtime and returned ephemerally in the early afternoon: only a few of the Argentine drivers returned to the track, in the company of Jean-Pierre Jassaud, before a downpour fell on the circuit in the porteña capital and interrupted all activities for the rest of the day. Jassaud was the only one who did anything noteworthy, managing to set times similar to Estéfano's ones.

Jean-Pierre Beltoise, driving the Matra in Argentina. The Frenchman was unstoppable in the 1967 F3 Temporada. (credits El Gráfico)

When Friday finally arrived, the pits at the Autodromo Municipal de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires really came to life. Friday's session was the last real opportunity for teams and drivers to make final adjustments to the machines, as the next day's training would define the starting positions for Sunday's preliminary races. Therefore, the polyphony of voices in the pits was significant, as the English, French, Italians, Swiss, Germans and Argentines chatted with each other, sharing tips regarding tuning and other race-related topics.

Jassaud remained the lone Matra representative, with Jean-Pierre Beltoise and Servoz-Gavin watching their teammate from Matra's pits. Jassaud tried to study the track as much as possible, transmitting all his knowledge to his teammates. The driver was not traveling as quickly around the circuit as in recent days, both because of the rain and because of the desire to maintain his machine as best as possible for qualifying in the afternoon.

This, on the other hand, seemed to be no problem for the Argentinians, who got the most out of their machines even in these insignificant training sessions. Bordeu, Pairetti and Cupeiro were very fast on the track, reaching marks close to the 1.42s.

Finally, the Saturday quali day arrived: in the morning, the first cars to enter the track were those belonging to the Matra Sports squad: Jean-Pierre Jassaud at the front, guiding the path of Beltoise and Servoz-Gavin. Less than a lap later, however, the team was the protagonist of a bizarre moment on the circuit.

Because of the knowledge he had gained in the previous days running around the track, Jassaud didn't realise he was faster than Beltoise and Servoz-Gavin, with the pair quickly losing their benchmark. At the beginning of the second lap, Beltoise, having to make the big Ciervo curve without reference, miscalculated and ended up in the run-off area, on the outside part of the bend. Servoz-Gavin, who was right behind, didn't pay attention to his teammate's mistake, and followed Beltoise into the runoff area. Luckily, none of the cars suffered any damage from the error.

At the same time, the first drivers began to set their times. 'Geki' and Cardwell stood out at first, moving quickly around the track, while female duo Rosadele Facetti and Natalie Goodwin put on a show in the first few laps. However, despite a good start, both Rosadele and Natalie were unable to keep pace with the rest of the field, falling several positions by the end of the qualifying session.

As the minutes went by, it seemed that the scales tipped more and more towards Matra. After recovering from their scares, both Beltoise and Servoz-Gavin returned to the track, this time with a more attentive Jassaud guiding the group – the pair did not take long to regain confidence and within a few laps, the team was locked in a personal duel for the lead. Jassaud seemed to be the fastest at the beginning, but it didn't take long for Servoz-Gavin to take over.

But in the end, it was Jean-Pierre Beltoise who demonstrated Matra's superiority over all its rivals, shattering the track record with a time of 1.39.1. John Cardwell had been the most surprising driver of the day: despite crashing and flipping his car at the Entrada a Los Mixtos in the middle of the qualifying session, he had managed to be the only intruder in the middle of les Bleus, achieving a time of 1.40. Servoz-Gavin and Jassaud came next, occupying third and fourth positions.

For the Argentinians, the qualifying session was not one of the most auspicious: despite Jorge Kissling showing excellent signs of potential in qualifying, the BWA proved to be a car far below the others, meaning that the driver was unable to escape the last positions of the grid; Nasif Estéfano was facing all sort of problems with his Lotus, which, after a collision with another vehicle, seemed to be struggling to be on pace with the rest of the field; in addition to Copello, who had transmission problems that prevented him from even leaving the pits. In the general context, the best national driver was Juan Manuel Bordeu, who took his Brabham BT15 to a reasonable 7th place.

Sunday, January 22nd arrived: the first duel of the Temporada was scheduled to take place on this date, with two qualifying heats, of 20 laps each, taking place on the circuit no. 2 of Buenos Aires. This variant, which was used in the Argentine F1 and F. Libre GPs between 1953-1960, was 3,912 metres long and consisted of the winding inner section (los Mixtos) and the looping of the Horquilla Larga curve (a part of the original Autodromo that was demolished at the end of 1971, when the track underwent an extensive remodeling process).

The first battery would feature 15 cars, with two of the Matras as prominent names (Beltoise and Servoz-Gavin), as well as some of the race winners from the last edition of the Argentine F3 Temporada: Eric Offenstadt and Charles Crichton-Stuart. After the official opening ceremony of the 1967 event, it was finally the drivers' turn to do what they did best: push to the limit.

The race start authorisation was given and it was Jean-Pierre Beltoise who took the lead, with Servoz-Gavin in second. Both Eric Offenstadt and Jorge Cupeiro had great moments in the first seconds of the race: the former exchanged fourth position for third, while the Argentinian gained several positions in the process – by the end of the first lap, Cupeiro was already up in fourth position.

Further back, luck seemed to have abandoned two other drivers: Giancarlo Baghetti, who in addition to being extremely sick because of a flu, had a more definitive problem when one of the engine valves broke inside the Cosworth of his Lotus, forcing him to retire after just two laps. Shortly afterwards, it was Crichton-Stuart's turn, who was also ill and simply gave up in the middle of the race.

Meanwhile, the front group changed its appearance a little, with Servoz-Gavin losing several positions after a mistake in one of the corners; an event from which the driver was unable to recover later in the heat. This allowed Offenstadt to move up to second and Cupeiro to third. But the Argentinian couldn't handle the pressure from Alan Rollinson and Jurg Dübler in the second half of the heat, giving up two positions before finally stabilising in fifth place.

With the battles at the front of the grid finally stabilised, Beltoise had no problem crossing the finish line first, with a time of 33.36.1, 5 seconds ahead of second-placed Offenstadt. Alan Rollinson rounded out the top three, with the second Matra driven by Servoz-Gavin ranking only tenth.

A few minutes were needed to clear the track before it was declared ready for the second heat. This time there were 14 starters, with names like Jassaud and Cardwell being the attractions of the show. But, at the start, neither of them shone; and surprisingly, it was Argentinians Pairetti and Bordeu who excited the Buenos Aires crowd, as the pair swallowed their European rivals at the start, with both taking the first and second positions before the Curvón.

But the Argentinians' joy didn't last long, as their rivals recovered from the shock: Jassaud regained the lead on the second lap, after a beautiful move executed at the entrance of the Mixtos. John Cardwell followed the Frenchman's lead, restoring order in the race hierarchy. While Bordeu had stabilised himself in a group made up of Vianini, Mohr and Regazzoni who were competing for third position in the following laps, Pairetti said goodbye to the dispute on lap 4, after a problem with his car's fuel pump.

The positions remained untouched until basically the final quarter of the race, when on the 15th lap Regazzoni (carburetor) and on the 16th, Mohr (rupture of a joint) abandoned the race. This allowed Bordeu to stay in a comfortable fourth place, as Vianini had already opened up some advantage over his pursuers. The fight for first place was already resolved, with Jassaud crossing the finish line five seconds ahead of second-placed Cardwell.

After the heats were finished, it was time to establish the starting grid for the main Sunday's race, which would last 35 laps. As the starting order would be based on the final times achieved by each driver in the preliminary heats, the cars were arranged as follows in the first two rows: with their view unobstructed were Jean-Pierre Beltoise (outside), Alan Rollinson (middle) and Eric Offenstadt (inside); Behind, in the second row, were Jean-Pierre Jassaud (outside) and John Cardwell (inside).

27 cars would take part in the first valid race of the 1967 F3 Temporada and, when authorisation was given, the teams were quick to push their vehicles into their respective positions on the grid. It was undeniable that most of the eyes were on Matra's blue cars, which had performed so well in the preliminary heats.

Jean-Pierre Beltoise (#28) leads the pack, closely followed by Frenchman Eric Offenstadt (#38). (credits Getty Images)

The flag was lowered and the vehicles accelerated along the main straight of the Autodromo Municipal de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Eric Offenstadt had the quickest reaction time, jumping in front of Beltoise's Matra. But, in less than half a lap, Matra had regained first position, with Offenstadt and his Lotus having to cling to a precarious second position. Bordeu was in third place, after another spectacular start: in less than 500 meters of track, the driver had gone from eighth to third, trying to stay very close to the French.

Before the end of the first lap, however, Dubler had managed to answer Bordeu, relegating the Argentinian to fourth place. At the end of the first lap, the leading group was arranged in the following order: 1st – J.P. Beltoise; 2nd – E. Offenstadt; 3rd – J. Dubler; 4th – J.M. Bordeu; 5th – J.P. Jassaud; and 6th – A. Rollinson.

In the second lap, Beltoise began to demonstrate that he would be at a level above his rivals that Sunday, already managing to put a difference of tenths between himself and Offenstadt. It didn't take long for these to increase to seconds, while Jassaud was now beginning to threaten the Lotus driver's second position. On the sixth lap, the threat became a concrete action, when Jassaud executed a beautiful move to create a Matra 1-2.

Offenstadt, now in third, focused on two frontlines: the one he saw in front of his eyes, regarding his duel with Jassaud, and one he saw through his mirrors, which was made up of pursuers Dubler, Rollinson and Cardwell. Bordeu had dropped to seventh position, now locked in battle with Italian Facetti, Argentinians Cupeiro and Marincovich, and Briton Lambert. Before ten laps were completed, Facetti had managed to overtake Bordeu who was now threatened by Chris Lambert, but luckily for the Argentinian, the Brit was unable to materialise his attack as on lap 14, the Cooper's rear suspension gave way, forcing the driver to drop out of the race.

The following laps were a Matra show, with each driver demonstrating a different facet of the team: J.P. Beltoise, who was racking up fast laps in the lead, definitively broke away from the pack; J.P. Jassaud demonstrated calm and tranquility, faced with an increasingly threatening Offenstadt behind him; and J. Servoz-Gavin had been carrying out a spectacular recovery race: after the initial ten laps, the driver had already entered the top ten, and when the marker reached twenty, the driver was up in fourth, just behind Offenstadt and his own two teammates.

Further back, the great battles of the first laps had turned into skirmishes of two to three cars each: Jurg Dubler continued to lead his small group, now pursued by Cardwell who had overtaken Rollinson before the 25-lap mark. Behind them, another trio with Bordeu, Mohr and Estéfano. The latter was in control of a Brabham that should have originally been driven by Carlos Martin in the race but due to mechanical problems with the Lotus, the ACA decided to assign the Brabham to Estéfano, who was now showing himself in good shape in the race.

At the same time, new events were developing in the front group: Jassaud could no longer handle the pressure, with a series of small errors allowing Eric Offenstadt to retake second place. In fact, the Frenchman's sequence of mistakes was so great that it allowed Servoz-Gavin and John Cardwell to get closer. The latter had freed himself from Dubler after the Swiss car began to slow down on the track.

Seeing the opportunity of an improbable podium within his reach, Cardwell drove the laps of his life, squeezing every last drop of performance that the Lotus still had. And to the driver's surprise, with five laps to go, he was in third place. But the Briton did not hold back until the end of the race and, in a moment of hesitation, Cardwell missed the entry into one of the corners. This allowed the Matras of Jassaud and Servoz-Gavin to sneak back into third and fourth positions.

However, Jean-Pierre Beltoise didn't even pay attention to the battle of his teammates, as the finish line got closer to the driver. And 58 minutes, 28 seconds and 6 tenths after starting, Beltoise crossed the finish line first, more than 20 seconds ahead of second-placed Offenstadt. Closing the podium of the Gran Premio Ciudad de Buenos Aires was Jean-Pierre Jaussaud, in a race filled with ups and downs for the French driver.

Even though they didn't get the 1-2-3 on the podium, Matra Sports had demonstrated that they hadn't come to Argentina for a vacation trip. Beltoise had put on an impeccable show on the circuit, leading almost from start to finish in the two races he had contested. Meanwhile, despite the mistakes of Jassaud and Servoz-Gavin, both had reached the end of the final race in the top positions – and, if it weren't for Offenstadt's heroic performance, the trio could well have swept the first race of the Temporada.

2. Gran Premio Ciudad de Mar del Plata (Mar del Plata, Circuito Golf)

Right after the race in Buenos Aires, the drivers and teams headed south, towards the city of Mar del Plata. The venue, which had hosted the last stage of the 1966 Argentine F3 Temporada, returned to the calendar to the joy of the organisers and the concern of the drivers. For this event, the Club Peñarol de Mar del Plata would be the representative of the ACA on site, being delegated by it to organise the event. The Club had been founded in 1922, as a local sporting entity.

The race had once again become one of the event's highlights, due to the popularity of the place at the end of January and beginning of February with Argentine and international tourists. It was expected that the Mar del Plata GP would generate good income, which (theoretically) would be beneficial to the development of Argentine motorsport.

However, this feeling of optimism did not infect the drivers; They knew that the street circuit, practically untouched since last year, would be a challenge for them and their machines. The track was notably uneven and any mistake meant colliding with either a pole or the crowd, which would certainly gather on the sides of the road. As in 1966, only a few straw-barriers were placed in some sensible parts of the track – which certainly did not represent any concrete security measure.

Even Juan Manuel Fangio himself, who accompanied Escuderia Automundo to Mar del Plata, was concerned about the conditions there, telling the press “[…] This (referring to the event preparations) is extremely dangerous. Anything can happen here.”

A factor that also worried the drivers was the little time they would have to get to know the track: since the circuit used part of the city's seaside boulevard, as well as other internal roads to make up the layout, it was impossible to close the track for a period of time longer than the weekend – so, practice sessions on Friday were out of question. Furthermore, one has to take into account the peak tourism season in the area, which meant that Mar del Plata had more intense traffic than normal – and we all know what a closed main street in an overpopulated city can do.

.Although some drivers were familiar with the route due to their participation in the 1966 edition, the majority of the field only had their first contact with the track on Friday; that is, two days before the race, which was scheduled to take place on Sunday, the 29th. Since traffic was not yet interrupted at the location, the only thing the drivers could do was observe the place as mere spectators, exchanging advice and observations.

On Saturday, the story would be different: in the morning, a free practice session was scheduled to take place, while in the afternoon, the real qualifying session would be held. For the first, the drivers wasted no time, with the first cars entering the track at 6:30 am. It didn't take long for the Matras to demonstrate their strength on the streets of Mar del Plata as well, with Servoz-Gavin and J.P. Jassaud quickly circulating around the circuit. Beltoise, on the other hand, was more conservative, going a little slower than his teammates.

But this was not a sign of the driver's dislike for the place or spectators. On the contrary, Beltoise aimed to sweep the championship, winning the four possible races in Argentina. He reaffirmed his objective in an interview with the local press, during training on Saturday: “I wouldn't mind so much (winning everything) in another country – I tell you – but Argentina is the land of J.M. Fangio.” In other words, this meant that the driver saved his machine as much as possible in less decisive moments, such as those of the free practice days.

Like the French, the Italians Antonio Maglione and Giovanni Alberti also tried hard on the track, but their good times were still far from those of the Matra squad. Another one who also deserves to be highlighted in the morning was British driver Charles Crichton-Stuart, who seemed to have recovered from his misfortunes in Buenos Aires. The champion of the 1966 Argentine F3 Temporada demonstrated that he would be fast that weekend – and that he would certainly be the biggest threat to the Matras' dominance.

The free session lasted until early afternoon, when the circuit was closed for cleaning and small repairs. The break lasted until almost 5:30 pm, when the cars were released again to set their official times. And, to the 'astonishment of no one', the Matras were the fastest! And the peculiar factor was that despite the three cars securing the top three positions, each driver achieved their mark through a different style.

Beltoise was the most aggressive, strongly attacking the curves of the trickiest section of the track, the zigzag between the Leandro N. Alem street and the Patricio Peralta Ramos Avenue. Johnny Servoz-Gavin tried to be cleaner, looking for the best trajectory in the curves while Jassaud was the most cautious, taking care not to get caught in the circuit's traps. In the end, it was Servoz-Gavin's tactics that paid off, with the driver, at the same time, being the fastest in the classification and setting the absolute record on the Mar del Plata circuit: 1.24.7. J.P. Beltoise would have the second-best time of the day with 1.25.9, and J.P. Jassaud would be third with 1.26.1.

John Cardell was the closest driver to get between the blue cars, being just two tenths off Jassaud's mark. Also worth noting is the performance of Eric Offenstadt, who once again managed to place himself among the top, setting fifth best time. For the Argentinians, this was another journey of bad luck: with the exception of Italo-Argentine Vianini who qualified his Brabham BT21 in seventh position, almost all the other drivers representing the celestial flag would start from the last positions. Especially affected were Escuderia Automondo and the ACA team, which were plagued with constant mechanical problems in their cars; problems which were mainly responsible for limiting the performances of its drivers.

The Italo-Argentine Andrea Vianini was another figure from the 1966 Temporada who returned for 1967 - only this time, the driver would race as a privateer. (credits Historia del Autodromo de Buenos Aires, photo colorised by the author)

For the following day, the 'heats plus final race' scheme would again be put into practice. The 27 cars would be divided between two groups, the first with drivers classified in odd positions (1,3,5,...) and the second in even (2,4,6,...) from the times set on Saturday. Each heat would be 25 laps long, with each driver's final times in the heats being used to form the grid for the final race. This would be 50 laps, which would be divided into two other heats, of 25 laps each, contested by all drivers (well, we can say that it was, at least, a very complicated and confusing scheme).

Early afternoon on Sunday, January 29, 1967. Under a summer sun, the first 13 drivers took their positions on the starting grid. All eyes were on Servoz-Gavin and Jassaud, the French duo who dominated the front of the grid in the first race of the day. Behind, Offenstadt and Regazzoni, two veterans of the Temporada. Everyone was ready and the start was given.

In the first corner, it was Servoz-Gavin who led the pack, followed by Clay Regazzoni, who jumped from fourth to second. J.P Jassaud followed soon after, with Offenstadt and Marincovich hot on his heels. The Argentinian, despite a mistake made at the entrance to the coastal boulevard at the end of the first lap, which led to a collision with some hay-bales, remained close to Offenstadt, not letting the Frenchman escape his sights.

At one point, the Argentinian managed to take fourth position, before a problem with the front left wheel on lap 13 forced the driver to retire from the race. By that time, Jassaud had already regained second place, with Regazzoni, Offenstadt and Crichton-Stuart fighting fiercely for the final position in the top-three. The first of the group to make a serious move was Offenstadt who overtook Regazzoni with less than 10 laps to go in the heat.

Then it was Crichton-Stuart's turn, who, seeing the Frenchman starting to distance himself, tried to overtake Regazzoni as soon as the opportunity arose. Luckily for the Swiss, who was starting to slow down on the track, his closest pursuer, Manfred Mohr, was reasonably far away, due to a long skirmish between him and Romano 'Tiger' Perdoni. Because of this, Regazzoni sat in his comfortable fifth place until the end of the 25 regulatory laps.

Further ahead, Charles Crichton-Stuart was trying to make up for the time lost to Offenstadt, but it was already too late. The Frenchman would cross the line seven seconds ahead of the Briton, thus securing third position in the heat. While these cars took the chequered flag, the Matras, already well ahead, were focusing on the final race. Servoz-Gavin finished the race in 36.37.2, 17 seconds ahead of second-placed Jassaud and 35 over Offenstadt's Lotus.

A few minutes apart and it was the turn of the second group, made up of 14 other vehicles. Engines at full rotation and the cars roared along the main straight of the Mar del Plata circuit. At the first corner, it was once again a blue car that was leading: Jean-Pierre Beltoise's Matra. Carlo Facetti, who had made a spectacular start, leaving the last positions, was already in fourth place at the end of the lap, sharing space with Rollinson, Dubler, Pairetti and Bordeu.

On the second lap, significant changes altered the face of the front group: two Beltoise tyres went flat, forcing the driver to take a long stop in the pits. Carlo Facetti, who continued at a fast pace, overtook Rollinson and Dubler, thus taking the lead of the race. For a few laps, this was the order of the top three, until Rollinson managed to take his Brabham to the lead. Dubler also managed to overtake Facetti, relegating the Italian to third place.

Behind, Bordeu had overtaken Pairetti, now threatening Facetti's tenuous third spot. The Italian from Scuderia Madunina resisted for a few moments, before the Argentinian found an opening to definitively take a place among the leaders.

Between laps 10 and 20, more action developed in this field: the first to change positions were Rollinson and Dubler, who were separated by thousandths until Jürg, taking advantage of a moment of his opponent's lack of attention, overtook him, placing the white and red colours of the Swiss flag in first position. Soon after, it was Bordeu's turn, who skillfully executed a series of moves on both drivers.

To the delight of the crowd, for the first time in this competition Argentina was truly leading a race. But the intense battles for the top positions had a negative effect on the leaders, as it allowed Moser and Cardwell to get closer. The two quickly became the biggest threats to Bordeu's leadership who defended himself as best he could from constant attacks.

All this combat raged on until lap 18 when Cardwell and Bordeu collided in the winding section between the city's cemetery and the Mar del Plata Naval Base. Rollinson was also involved in the accident, colliding with some debris that had dropped from the cars during the crash. This meant that the lead fell into Moser's lap who would not lose it until the end of the race. Carlo Facetti was second, crossing the finish line less than half a second behind the Swiss driver. In third place, another driver of the Alps region was Jürg Dubler.

Beltoise had made an incredible recovery race, as despite spending countless laps in the pit, the Frenchman had finished just two laps behind the winner Moser. In the final heat standings, the driver managed to take the Matra to sixth position, making good use of the incidents that affected the leaders in the final laps of the heat.

A long pause followed at the end of the preliminary heats. Teams and drivers prepared to return to the track, but authorisation to return did not appear. Almost an hour passed before the vehicles were finally allowed to head to their starting positions. Servoz-Gavin and Jassaud would lead the line, followed by the remaining 25 drivers.

Carlos Marincovich returns to the pits, after one of the qualifying sessions at the Mar del Plata circuit. (credits A Todo Motor TV)

The flag was lowered and the first of the two races that would define the winner of the Gran Premio Ciudad de Mar del Plata began. Servoz-Gavin tried to secure the lead, closely followed by his teammate Jassaud. Crichton-Stuart was right behind the pair, with Beltoise quickly moving up through the grid. At the start of the second lap, the Matra cars were already positioned in single file, dominating the first three positions on the standings. It was at this exact moment that J.M. Fangio's prophecy began to materialise in Mar del Plata.

Young Carlos Martin, who was at the back of the field, struggled to keep the reluctant Lotus 41 on the track. This was the same car that Nasif Estéfano had tried to tame on the Buenos Aires circuit and, being unsuccessful in this task, exchanged for one of the Brabhams from the ACA team. As mentioned previously, this Brabham was Martin's original car, who was obliged to give the machine to the team's most experienced driver.

With no choice left to him, the driver tried his luck on the ill-fated Lotus. The problem was that if the experienced Nasif hadn't managed to impose his will on the car, young Martin would not have had any chance with the machine. And so it was, as the driver paid with his life on the streets of Mar del Plata.

Right at the first curve of the second lap, at the junction between the Patricio Peralta Ramos and Juan B. Justo Avenues, the driver failed to hit the apex, lost control of the machine and hit the street curb. The car was catapulted towards the crowd that had gathered at the side of the track, injuring several spectators and killing the driver instantly. Then the real chaos begins on the circuit, with people and emergency vehicles entering and circulating through the track.

Meanwhile the race progressed, with the drivers, in addition to paying attention to their opponents, having to dodge pedestrians who indiscriminately invaded the track to escape the chaos that was taking place in the area close to the accident. Servoz-Gavin would lead the field until lap 8 when Jassaud overtook his teammate.Servoz-Gavin remained on track for another two laps until a mechanical problem made him go straight into the French team's garage.

Just as Servoz-Gavin lost the lead, the second serious accident of the day developed. Kissling and Marincovich were competing for positions at the back of the field until their tangling of wheels caused the BWA to be sent flying. The car landed only on the side of the road, damaging the vehicle to some degree. Luckily, there were no people at the scene, and the driver emerged unharmed from the crash.

Returning to the fight for leadership, the confrontation now developed between Jassaud, Crichton-Stuart and Beltoise. The latter only remained on the lookout, observing the duel that developed between his teammate and the Briton. Shortly after ten laps, Crichton-Stuart finally managed to overtake his rival, taking the lead. Jassaud and Beltoise now joined forces, planning a devastating counterattack against the British driver.

.However, it would not take long for the whirlwind of chaos to deepen in Mar del Plata, as on lap 15, Rosadele Facetti, who was in the midpack of the field, lost control at the tight curve of the Calle Formosa which was the exit of the trickiest part of the track. The Brabham (Rosadele's main car, the Tecno TF/66, was going through some repairs after Buenos Aires) failed to react to the driver's input and ploughed straight into a group of spectators that had crowded at the scene. The accident killed at least two individuals at the scene – one of them, a member of the Club Penãrol de Mar del Plata committee – in addition to leaving at least two dozen people seriously injured. Rosadele, miraculously, got out of the vehicle with only minor bruises.

The Italian driver's accident triggered a cascade effect through the crowd, that after discovering that yet another fatal accident had occurred, began to demand the immediate end of the race. The police and the spectators diagreed on the course of action to take, so a huge fight erupted on the sidelines of the circuit, as a complete scene of chaos developed around and inside the track. Without any official statement from the organisers about the end of the race, the event continued, so the crowd decided to take justice into their own hands.

Soon, any nearby objects were being thrown onto the track, such as straw bales and any trash on hand. Fire hydrants were violated and water began to pour out of certain parts of the track, making the environment even more dangerous and hostile. In the end, not even the drivers escaped, with objects being thrown at vehicles traveling at almost 200kph. After the first 25 laps, the drivers were the ones who rejected any slight chance that still existed of competing in the remaining heat.

At the end of the heat, the winner of the race was Beltoise, as the Frenchman had taken advantage of the chaos of the final laps to strike a decisive blow with his teammate, Jassaud, against Lythgoe-Goodwin Racing's Briton, Charles Crichton-Stuart. The offensive had the desired success for the French drivers, who secured first and second positions on the podium. Crichton-Stuart didn't have any problems securing the third place, thus returning to some of his 1966 form, giving him a good result on that sad afternoon in Mar del Plata.

The thing is that the chaos of the 1967 race at Mar del Plata could have been easily avoided, if at least some of the warnings given about the track's unsafety had been heeded. In addition to Fangio and the drivers, it later emerged that some motorsport reporters assigned to cover the event had alerted the local police and organisers several times about problems with the track, already on the day of practice and qualifying (Saturday).

As many of these journalists were specialised in covering motorsports in different parts of Argentina, they quickly recognised the failures of the ACA as well as the inexperienced Club Penãrol de Mar del Plata. Even so, nothing was done by either institution to even minimally remedy the situation between Saturday and Sunday – and the result was the fateful race on January 29th.

3. Gran Premio Ciudad de Córdoba (Córdoba, Circuito Escuela de Aviación)

Despite the disastrous race in Mar del Plata, the 1967 Temporada would continue with its calendar unchanged, its next stop being the city of Córdoba, 700 kilometres northwest of Buenos Aires. It was expected that the Córdoba Automóvil Club, designated by the ACA to organise the event, had learned from the mistakes committed by the Club Penãrol, with a view to promoting an event much more prepared than its predecessor. And there were no excuses, as the race would be held at the Escuela de Aviación Militar airfield, on the outskirts of the city.

But right from the start, things started to go wrong once again: when the drivers arrived at the track on Friday afternoon, they were distressed to discover that much of the track demarcation work was still to be done, with hay bales being placed on the straights and sandbags on the curves. The latter proved to be the biggest concern: the sandbags were just an unnecessary hazard, as a high-speed collision with them could certainly cause damage to a car and serious injury to a driver. Such a measure made no sense, especially in the context of the Córdoba track itself, set up on an aerodrome with large runoff areas.

Even so, the organisers' concern about not leaving any room for problems overcame the common sense of the situation – and in the end, the sand protections were maintained. It was only at 6:30 pm on Friday that the track assembly work was completed; and, minutes later, the first Formula 3 drivers were already experiencing the place, taking their first practice laps on the circuit.

The 3462-metre-long circuit was quickly taken over by drivers, who sought to take advantage of the little time still left of daylight to become acquainted with the tracks' tricks. The Matras of Beltoise and Servoz-Gavin were the highlights of the day, as they had now a suitable location to release the maximum horsepower of their engines. Beltoise went fastest with a lap of 1.33.2. Clay Regazzoni and Carlo Facetti were the other drivers who stood out positively on the first day of activities in Córdoba.

On Saturday morning, the history of the 1967 Córdoba GP really began to be written. The first part of official practice was scheduled to take place early in the morning, with frantic movement in the pits as soon as the day lightened over the area. A positive surprise awaited the teams and drivers when they arrived at the scene: seeking to redeem itself from its organisational problems the previous day, the Córdoba Automóvil Club had decided to impose strict control over the movement of people during the weekend.

The audience was directed to marked and exclusive areas, away from dangerous points on the track. This measure was immediately felt by teams and drivers, who now had more space and peace of mind in the pits. This allowed the teams to focus solely on their cars, and not on controlling intruders in sensitive areas (such as the pit-stop zone, garages, etc.). The result was extremely positive, with a safer and more dynamic organisation than that seen on previous weekends.

Returning to the activities themselves, it was Argentinians Bordeu and Pairetti who christened the track on Saturday. Both spent a few laps alone, before other drivers joined the pair. Both Bordeu and Pairetti tried to get the most out of their cars, but, at the end of the day, they achieved little, remaining only in the middle positions of the field.

Facetti, Dubler and Moser were others to try their luck early on. The first two suffered some setbacks, leaving the track a few times throughout qualifying. The most problematic place for the drivers was turn 4, which was a taxiway that connected the aircraft parking area with an auxiliary road on the runway. At that exact point, there was a slight undulation in the pavement, due to a patch in the pavement made by military personal based on the airfield. Not only Dubler and Facetti faced problems on the spot, but so did several other drivers throughout the weekend.

Despite this, it would be Jürg Dubler himself who would have the fourth best time, with a time of 1.32.1. This time was achieved with difficulty, as in addition to the spins, the driver was involved in a long-time duel with Alan Rollinson, each driver breaking the other's mark several times. Although the Briton had the advantage in the final part of the session, in the end, it was the Swiss who triumphed.

The Matra trio also went on the offensive mode early in the morning. Repeating their Buenos Aires strategy, the three drivers drove together in single file during the first laps, with Beltoise in the lead this time, followed by Servoz-Gavin and Jassaud. The team leader would return to the pits a few laps later, to check his machine and pass observations to the Matra mechanics, leaving only the duo Servoz-Gavin and Jassaud to set times.

Both did not take long to lower the mark set by Beltoise the previous day, with the driver of car #30 being the fastest. Johnny Servoz-Gavin would set the new track record, with a time of 1.31.1, with an average of 135.710kph. After returning to the track, Beltoise tried his best to reestablish himself as the fastest driver in Córdoba – but the best the driver could achieve was to be four tenths off the pace of his teammate, which would give him second best time of the day.

Jean-Pierre Jaussaud locked out the first three positions for Matra despite the fact that the driver hit the grass twice. But the French manufacturer's cars were so well balanced that this was just a minor detail in the classification, with Jassaud finishing just tenths behind his teammates.

Juan Manuel Bordeu had once again proven himself to be one of the most competent Argentinians on the grid, managing at times to compete for the top positions. (credits F1 Forgotten Drivers)

Due to the scorching heat that embraced Córdoba at the beginning of February, most of the important qualifying action described above took place in the morning. Before 11:30 am, many of the teams had already left the track, hoping that weather would cool down a little in the afternoon. Such conditions mainly affected the machines, as engine overheating began to become the biggest headache for drivers and teams.

The few drivers who tried to venture onto the track in the early afternoon sought to mitigate the heat problem with simple solutions, as in the case of Manfred Mohr: the German simply removed the protective hood from his MAE engine with the aim of improving air flow and cooling of the powerplant. Even though the objective was achieved, the return was not so good for the driver, as the removal of the fairing negatively affected the Brabham's aerodynamics; in the end, a measly 15th position was reserved for Mohr.

After a day of extreme heat, the end of the day breeze came as a relief for everyone in the pits. Saturday quickly gave way to Sunday and another day of bright sun settled over the city in the heart of Argentina. 25 were ready to compete in the Gran Premio Ciudad de Cordoba, valid as the third round of the 1967 Argentine F3 Temporada.

Despite intense questioning about the system, once again the race would be contested using elimination heats, which would define the starting positions for the final race. This format was already a central topic of discussion even before the Mar del Plata leg, as it was argued that the heat formula failed to work efficiently.

In other words, the qualifying heats were only useful from a commercial point of view, as they considerably increased the time the cars were exposed to the crowd, due to the countless races. However, it was argued that from a sporting point of view, such a formula did not present any gain, since no one was eliminated in such events – therefore, what was the point of having elimination heats without any elimination? Furthermore, such races only served to increase the cars' attrition rate, considerably decreasing their performance in the main event at the expense of useless races such as the preliminary heats.

Even so, such questioning was not enough to change the planning line drawn up by the ACA, which would maintain it at least until the end of the 1967 F3 Temporada. Because of this, the first heat contested by 13 cars in 20 laps didn't take long to get underway.

Rollinson started better than Servoz-Gavin and Jassaud, taking the lead in the first metres of the race. But Servoz-Gavin's reaction was quick and withering, with the Frenchman retaking the lead before the end of the first lap. Rollinson was second, followed by Jassaud, Andrea Vianini, Offenstadt and Moser. Jassaud would have problems in the next few laps, being yet another victim of the entry into turn 4. Luckily, the driver quickly recovered from the scare, controlling his car before skidding onto the grass. Jassaud had lost several seconds in the process – something that was enough to drop the Frenchman from third to sixth.

At this point, Offenstadt had already moved up to third place, leaving the fight between Vianini and Moser to unfold just behind. But a quick look in the rearview mirror on lap 6 revealed that the pair were no longer behind the French driver; This was because in one of the corners, both drivers went in too aggressive, as a result colliding in the process. Despite emerging unharmed from the accident, both machines were heavily damaged: Moser's left front tyre had almost been torn off in the impact, while parts of Vianini's rear suspension were lying on the track.

After the accident, little action developed on the airbase circuit, as Servoz-Gavin sought to increasingly secure his lead, with Alan Rollinson and Eric Offenstadt very comfortable in their respective second and third positions. Jassaud was desperately trying to make up for lost time, but the gap between him and Offenstadt was too great to be closed in 20 laps. In the end, Servoz-Gavin crossed the finish line with a total time of 30.53.9, just over 15 seconds ahead of Rollinson. From then on, another 24 seconds would pass before third-placed Offenstadt crossed the finish line, with a desolate Jassaud much further behind.

A brief pause followed before it was the turn of the remaining 12 cars to perform at Córdoba. Authorisation to start was given and all cars, set off for the first of the 20 laps of the heat. Beltoise had no problem consolidating his first position, with the rest of the field fighting for the remaining positions in the top-three. Crichton-Stuart in second and Jürg Dubler in third were the first to occupy these positions. In the second lap, however, it was Nasif Estéfano who was in second place, relegating Crichton-Stuart to third place. Soon after, Dubler resumed third place, with the British Stuart being forced into a duel with his compatriot John Cardwell for fourth position.

Shortly after ten laps, another change at the front: Dubler returned to second position, with Cardwell now in third. Nasif Estéfano, who was performing so well in the race, had engine overheating problems that forced him to reduce his pace in the second half of the race; In the end, the Argentinian would only be in fifth place, far away from the race leaders.

At this point in the race, Beltoise was well up the road with an advantage that got bigger and bigger until it materialised into a 15-second gap that the driver had built up to second-placed Dubler at the chequered flag. Finishing in third place was the same Cardwell who had managed to definitively distance himself from Crichton-Stuart in the final laps of the race.

After the qualifying heats held in the morning, a long break was scheduled, thus avoiding holding the main race of the day in the hotter hours, especially in the early afternoon. The stewards' concern with this point was already evident in the qualifying heats themselves, when many of the cars were unable to reach the final checkpoint due to the heat, which easily overheated the machines. For example, in the first heat, of the 13 cars that started only five had reached the end of the 20 laps; in the second, of the initial 12 just six managed to complete the total distance.

Because of this and to give some time to teams to repair their chassis, it was only at 7pm that the cars lined up again on the grid. Servoz-Gavin, Beltoise and Rollinson shared the front row, with the other 20 competitors close behind. Flag given, and Beltoise jumped into the lead, with Servoz-Gavin in second place and Rollinson in third. Dubler and Offenstadt were at the forefront of this group, while Jassaud began his recovery campaign.

While the front trio was a few seconds away, the chasing group increased in size: in addition to Dubler and Offenstadt, Cardwell, Crichton-Stuart, Estéfano and Jassaud entered the dispute for positions just behind the podium, with the drivers changing positions frequently in the first laps. It didn't take long, however, for Jassaud to demonstrate the strength of his Matra, as he vanquished all his rivals in this field.

Further ahead, the group remained untouched, with Beltoise and Servoz-Gavin defending each other, while Rollinson continued to lie in wait. On lap 5, a serious accident at the back of the field occurred, as Giovanni Alberti and Romano Perdomi, who were competing for positions, collided in the corner leading onto the finishing straight, with Alberti being catapulted out of the car in the process. The driver was immediately taken to the military hospital of the airbase while the collision generated a long yellow flag.

As the pace of the race decreased, there were few changes until the end of the first third of the contest. It was at that moment that the first drivers began to have problems because of the heat. The first victim was Alan Rollinson, who on lap 15 was forced to retire into the pits. This once again promoted Matra into occupying the top three positions, a fact that didn't last long as on lap 17 Servoz-Gavin had to visit his garage early.

At the beginning of lap 20, the field competing for the podium positions was lined up like this: in first place, Beltoise, with an advantage of more than twenty seconds over his teammate Jassaud, who was in second place. A few seconds behind were Crichton-Stuart and Cardwell, fiercely competing for third place. A little further back another group, formed by Dubler, Offenstadt and Bordeu. The Argentinian managed to overtake his two rivals in just a few laps, taking fifth position and relegating Dubler and Offenstadt to sixth and seventh positions respectively.

A couple laps later, the Frenchman would definitively say goodbye to the race, after his Lotus' engine caught fire on lap 23. Dubler, however, would sometimes try to respond to the Argentinian's move, but without success the Swiss opted to secure sixth place.

After that, little happened in the race: Beltoise and Jassaud tried to keep it safe after having opened up an advantage over their pursuers, while Crichton-Stuart managed to get rid of Cardwell in the final few laps. The 35th lap arrived and with it, the black and white chequered flag synonymous of victory and glory was dropped. Once again, such words were synonymous with Jean-Pierre Beltoise who took his third consecutive win in the land of the pampas. Jassaud would take his Matra home in the second place, while Temporada veteran Crichton-Stuart held on to third place.

The three victories achieved by the Frenchman in the three races contested had basically declared the driver overall winner of the 1967 Temporada, with an absurd combination of results the only way for the trophy to end up in the hands of Jassaud, the only other driver still in contention. For Beltoise, with his objective already accomplished, it was now time to focus on the final mission of the French adventure in the lands south of the equator: completing the final stage of Operación Argentina.

4. Gran Premio Argentino (Buenos Aires, Variant Nº 2)

It was time to go back to where it all started: Buenos Aires. The Autodromo Municipal was preparing to host the last leg of the Temporada in a very dull atmosphere, compared to the same place that had hosted the opening of the event a month earlier. The title race was almost resolved, while most teams were already making preparations for the return journey to Europe. Many of the cars and drivers were showing signs of fatigue, which added a slower tone to that weekend.

For the Friday before the race, an open track day was scheduled on the agenda, with the drivers having all the time available to carry out tests and adjustments to the machines. Even though it was a free testing day, the ACA had determined that each driver should complete at least 10 laps on the circuit (a minimum that would also be applied to the qualifying sessions), otherwise they would not be allowed to participate in Saturday's qualifying sessions. Despite the terrible heat that had chased the drivers from Córdoba to the capital Porteña, the ACA had been irreducible in its position.

Even so, many teams decided to challenge the Argentine body's position; such as the Ron Harris Racing Division, which spent the entire Friday with its cars parked in the team's makeshift workshop. Same case with Martinelli + Sonvico Racing Team, which also prioritised an in-depth mechanical review over an afternoon of practice under a scorching sun. In the end, unable to veto all these teams, the ACA gave way, and the 10-lap rule was later abolished.

On Friday, almost no major activity took place on the circuit. Only a few drivers from Scuderia Madunina and Matra Sports, as well as a few other representatives from other teams, offered to take a few laps around the place.

For the French team, the day was a problematic one. Johnny Servoz-Gavin, after a few laps, felt that the gearbox was not working properly. Stopping in the pits for a more thorough inspection, it was confirmed that there was also a problem with the car's engine. Soon after, the car was taken to the garage, never to return to the track that day.

Next on the French team's headache list was Jean-Pierre Beltoise. After a public relations tour carried out by Matra in partnership with Peugeot during the morning, the driver arrived at the circuit in the Argentine capital in the early afternoon. Despite setting the fastest lap of the entire day, with a time of 1m40s, the Frenchman did not complete more than a combined 8 laps on the track, due to engine problems and the car's skittish performance on the bends of the track.

J.P. Jassaud was the one of the trio who spent the longest time on the track, achieving on average times 1 second slower than those set by Beltoise. Despite the effort, Jassaud had to abandon his attempts to beat his teammate's mark after 10 laps, due to failures in the Matra's braking and suspension system.

Swiss driver Jürg Dubler doing a reconnaissance lap around the Buenos Aires circuit.

(credits Historia del Autodromo de Buenos Aires)

The drivers closest to the French that day were Alan Rollinson (1.42) and Nasif Estéfano (1.42.1), who also put on a little show before retiring to their respective pits. Giancarlo Baghetti, who had struggled throughout the championship because of problems with his Lotus 41, had taken advantage of that day to test something new in Buenos Aires: the Italian had borrowed his teammate Alfredo Simoni's Tecno, to take a few laps around the track. The result wasn't that bad, with Baghetti achieving a time of 1.45.7.

In the early hours of Saturday, however, movement returned to normal at the Autodromo Municipal de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Teams were already carrying out their morning ritual of preparing the machines; on the other hand, the drivers also did their thing, exchanging information and tips with their contemporaries; In the end, the rivalry existed only inside the track, while outside, the common environment for everyone was anxiety about the future, as in a few days, Argentina would give way to Europe, as once again, it became the epicentre of Formula 3.

As had happened in almost all stages up to this point, most drivers took advantage of either the morning or the late afternoon to set their best marks. Despite some problems persisting in the cars from the previous day, Matra Sports continued its unbeatable form, placing itself once again as the fastest of the day. J.P. Beltoise would set a time of 1m40s, while J.P. Jassaud (1m40s4/10) and J. Servoz-Gavin (1m41s) would have the second and third best marks.

Alan Rollinson, who had done so well the previous day, had to settle for only eighth best time, while John Cardwell would take on the role of 'chaser' of the French cars, taking fourth place. Another driver who was doing well in the classification that day was Silvio Moser, who seemed to be inspired after receiving the news that he had become a father the day before. The Swiss ended the day with the fifth best time, and only by two tenths did the driver not steal fourth from Cardwell.

On the Argentine side, the highlights were J.M. Bordeu and Eduardo Copello, who took seventh and ninth positions, respectively. Bordeu's mark was rather surprising, given that the Argentinian would spend most of Saturday in the pits due to electrical problems on his Brabham.

On Sunday, very early in the morning, the last chapter of the 1967 Argentine F3 Temporada began to unfold. Before the qualifying heats, J.P. Beltoise, J. Servoz-Gavin, C. Crichton-Stuart and J. Dubler were authorised to do some laps around the track in order to check the condition of their vehicles after repairs made the day before. The drivers had made the request to carry out such tests on Saturday, after the end of the qualifying session – but as the original request was denied by ACA officials present at the scene, the counter-offer made provided for a few minutes of free track for the drivers as soon as the day dawned in Buenos Aires.

All four drivers were satisfied with the work done on their cars and as soon as they left, the GP apparatus began to come into operation. Only 23 cars were still in racing condition, and the vehicles were once again divided into two groups for the preliminary heats, each lasting 20 laps.

The first heat developed almost in a protocol fashion: Beltoise and Servoz-Gavin took the lead, leaving the other drivers with the responsibility of fighting for third place. 'Geki', Moser and Rollinson were the protagonists of this battle in the first laps, with the Italian actively contributing to the public's entertainment until lap 8 when his car's oil pressure reached 0 and he dropped out of the race.

Moser and Rollinson continued their duel, now followed by Frenchman Offenstadt – he was another one hit by bad luck, when six laps later one of the cylinders of his Holbay engine broke inside the engine. Once again, the Brit and the Swiss were alone, with both fighting unpretentiously for third place, which no longer meant anything in the race. In the end, it was Rollinson who took third place, after definitively overtaking Moser in the final laps of the heat.