Rear View Mirror,

Volume 9, No.1

Author

- Don Capps

Date

- April 13, 2011

Download

- RVM Vol 9, No 1 (PDF format, 787kb)

“Pity the poor Historian!” – Denis Jenkinson | Research is endlessly seductive, writing is hard work. – Barbara Tuchman

Christopher Hilton: An Appreciation

In late November 2010, Christopher Hilton died while on a research visit to Germany. Hilton wrote literally dozens of books, most being biographies of contemporary racing drivers – Senna da Silva and Schumacher being frequent subjects, but he also wrote about other topics in motor racing as well as other sports such as cricket and football. In addition, Hilton wrote several books relating to German history, the 1936 Olympics being one topic that seemed to fascinate him.

While many of his motor racing books were airily dismissed by many of us, they sold and seemed to be a steady source of income. Hilton kept a steady flow of these books coming, but he also began to show that he was not just some hack who popped out books fashioned around a biographical template for the rabid fanboyz. To no small, undisguised surprise to many, he also started to produce books that showed a genuine interest in the history of automobile racing.

Hilton was blessed with the virtue of being a good writer. He had been, after all, a sports journalist and had his craft forged in the fires of the literal race to meet the tight, almost impossible deadlines that are part and parcel of the newspaper business. Chris Hilton also seemed to be a good case for my personal belief that it is easier to turn a good writer with excellent research skills into a historian than the other way around.

Hilton’s book on the Donington races was a pleasant surprise. Surely, one could quibble with some of what he wrote, but the book was obviously the work of someone who wanted to write a good book on motor racing history. For the most part, he succeeded very well, especially for what was an initial foray into this realm.

Then, out of the blue I got word that Hilton wished to contact me. He was writing a book on Tazio Nuvolari and it seems that I had been the cause of a whole section of his research being tossed out the window and he was now faced with the problem of rewriting the chapter regarding the 1933 Gran Premio de Tripoli. After an exchange of emails regarding various aspects of what I had found, we had a nice chat or two about the material. Most of that talk ended up reflected in the revised chapter as well as in the notes for that chapter in his book on Nuvolari. He was very gracious and almost embarrassing in his thanks for the help provided for the chapter on the Tripoli race and other insights that were provided on Nuvolari. I still blush when I read his inscription on the copy of the Nuvolari book that he sent me when it was published.

Chris Hilton was quite different from what I had expected, his emails had started me thinking that he was quite serious about “getting this right.” After all, he could have just as easily dismissed what I had written and gone with the usual mythology as provided by Neubauer. That he did not and went with the dissenting voice understandably impressed me. He was very gracious when we talked and asked very good questions, clearly demonstrating that he had taken his time to conduct a great deal of research on his subject.

After this, I bought a number of his books. While not always in agreement with some items or issues in the books, scarcely a surprise since I can scarcely stand to read anything I have written without quibbling and moaning and groaning, they were inevitably interesting and well written, the latter going a long way in view of things, especially given the usual drudgery that is involved in reading the usual product that manages to get published.

As is always the case, his death was a genuine shock and reason for once more giving bite to the truth that we never seem to know what we have in our midst until it is gone. It was my honor and my great privilege to have had the opportunity, although even a small one, to work with Chris Hilton. He is certainly missed.

American Contests

1

1

A Listing of Automotive Contests from a 1908 Yearbook

What follows is a listing of automotive contests until the end of the 1907 season from a yearbook that appeared in 1908.2 Although it quickly becomes very evident that the listing quite incomplete, with any number of events of some consequence not being included, it does provide an idea as to the length and breath of the automobile racing scene in the United States at this time.

14 April 1900 / Merrick Road, Long Island: Springfield to Babylon and return

3

3

- 20 April 1901 / Long Island AC: 100 Mile Endurance Run

- 15 June 1901 / Boston: Country Club of Brookline

- 30 August 1901 / Newport: Acquidneck Park

- 9 September to 13 September 1901 / ACA 500 Mile Endurance Run: New York to Buffalo

- 26 September 1901 / Buffalo: Fort Erie

- 27 September 1901 / Buffalo: Fort Erie

- 28 September 1901 / Buffalo: Fort Erie

- 10 October 1901 / Detroit: Grosse Point

- 17 October 1901 / Providence: Narragansett Park

- 18 October 1901 / Providence: Narragansett Park

- 18 October 1901 / Joliet

- 16 November 1901 / New York: Brooklyn, Coney Island Boulevard

- 25 November 1901 / Cincinnati: Oakley Park

4

4

- 30 May 1902 / New York: Staten Island, South Shore Boulevard

- 23 August 1902 / New York: Brooklyn, Brighton Beach

- 16 September 1902 / Cleveland: Glenville Driving Park

- 24 September 1902 / Providence: Narragansett Park

- 9 October to 15 October 1902 / ACA 500 Mile Reliability Run: New York to Boston and return

- 24 October 1902 / Detroit: Grosse Point

- 25 October 1902 / Detroit: Grosse Point

- 27 November 1902 / Newark: Eagle Rock hillclimb

5

5

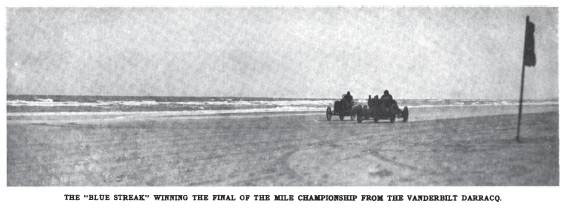

- 26 March 1903 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 27 March 1903 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 28 March 1903 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 20 April 1903 / Boston: Commonwealth Avenue hillclimb

- 30 May 1903 / New York: Yonkers, Empire City

- 20 June 1903 / Pittsburgh: Highland Park

- 11 July 1903 / Pittsburgh: Beechwood Avenue, Highland Park

- 26 July 1903 / New York: Yonkers, Empire City

- 4 September 1903 / Cleveland: Glenville Driving Park

- 5 September 1903 / Cleveland: Glenville Driving Park

- 7 September 1903 / Detroit: Grosse Point

- 8 September 1903 / Detroit: Grosse Point

- 19 September 1903 / Providence: Narragansett Park

- 3 October 1903 / New York: Yonkers, Empire City

- 7 October to 15 October 1903 / NAAM Endurance Run: New York to Pittsburgh

- 31 October 1903 / New York: Brooklyn, Brighton Beach

- 26 November 1903 / Newark: Eagle Rock hillclimb

6

6

- 27 January 1904 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 19 April 1904 / Boston: Commonwealth Avenue Hill hillclimb

- 30 May 1904 / Boston: Readville

- 30 May 1904 / Philadelphia: Point Breeze

- 11 June 1904 / Boston: Readville

- 4 July 1904 / Dayton: Fair Grounds

- 11 July 1904 / White Mountains: Mt. Washington hillclimb

- 12 July 1904 / White Mountains: Mt. Washington hillclimb

- 16 July 1904 / New York: Yonkers, Empire City

- 18 July 1904 / New York: Yonkers, Empire City

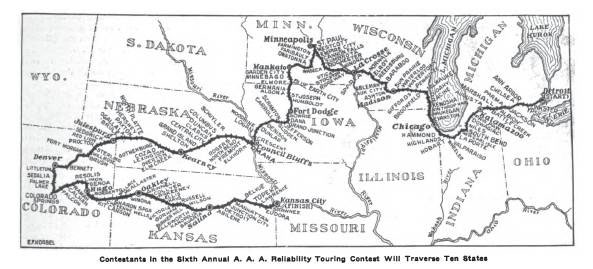

- 25 July to 10 August 1904 / AAA New York to St. Louis Tour

- 31 July 1904 / Newport: Sachuset Beach

- 18 August 1904 / Minneapolis: State Fair Grounds

- 23 August 1904 / Omaha: Omaha Driving Track

- 26 August 1904 / Detroit: Grosse Point

- 27 August 1904 / Detroit: Grosse Point

- 28 August 1904 / St. Louis

- 12 September 1904 / Providence: Narragansett Park

- 24 September 1904 / New York: Yonkers, Empire City

- 8 October 1904 / Long Island: Vanderbilt Cup

- 15 October 1904 / Cleveland: Glenville Driving Park

- 22 October 1904 / New York: Brooklyn, Brighton Beach

- 5 November 1904 / New York: Yonkers, Empire City

- 6 November 1904 / San Francisco

- 7 November 1904 / San Francisco

- 8 November 1904 / San Francisco

7

7

- 24 January 1905 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 25 January 1905 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 26 January 1905 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 27 January 1905 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 28 January 1905 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 30 January 1905 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 31 January 1905 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 6 May 1905 / New York: Brooklyn, Brighton Beach

- 22 May 1905 / New York: Morris Park

- 25 May 1905 / Worchester: Dead Horse Hill hillclimb

- 27 May 1905 / Chicago: Harlem

- 29 May 1905 / Chicago: Harlem

- 30 May 1905 / Chicago: Harlem

- 30 May 1905 / Boston: Readville

- 30 May 1905 / New York: Yonkers, Empire City

- 2 June 1905 / Milwaukee

- 3 June 1905 / Milwaukee

- 16 June 1905 / Hartford: Charter Oak Park

- 17 June 1905 / Hartford: Charter Oak Park

- 26 June 1905 / Minneapolis: Riverside Hill hillclimb

- 28 June 1905 / Pittsburgh: Brunots Island

- 29 June 1905 / Pittsburgh: Brunots Island

- 3 July 1905 / New York: Morris Park

- 4 July 1905 / New York: Morris Park

- 8 July 1905 / St. Paul: Hamline Track

- 10 July 1905 / St. Paul: Hamline Track

- 11 July to 22 July 1905 / Glidden Tour: New York to Bretton Woods and return

8

8

- 17 July 1905 / White Mountains: Mt. Washington hillclimb

- 18 July 1905 / White Mountains: Mt. Washington hillclimb

- 29 July 1905 / Cape May

- August 1905 / Peoria

- 7 August 1905 / Detroit: Grosse Point

- 8 August 1905 / Detroit: Grosse Point

- 12 August 1905 / Cleveland: Glenville Driving Park

- 14 August 1905 / Cleveland: Glenville Driving Park

- 18 August 1905 / Buffalo: Kenilworth Park

- 18 August 1905 / Cincinnati: Oakley Fair

- 19 August 1905 / Buffalo: Kenilworth Park

- 19 August 1905 / Long Branch: Elmwood Track

- 22 August 1905 / Long Branch: Elmwood Track

- 25 August 1905 / Cape May

- 26 August 1905 / Cape May

- 4 September 1905 / Atlantic City: Ventnor Course

- 5 September 1905 / Atlantic City: Ventnor Course

- 9 September 1905 / Boston: Readville

- 23 September 1905 / Providence: Narragansett Park

- 23 September 1905 / Long Island: Vanderbilt Cup American Elimination

9

9

- 14 October 1905 / Long Island: Vanderbilt Cup

10

10

- 23 January 1906 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 24 January 1906 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 25 January 1906 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 26 January 1906 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 27 January 1906 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 29 January 1906 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 26 April 1906 / Atlantic City: Ventnor Beach

- 27 April 1906 / Atlantic City: Ventnor Beach

- 28 April 1906 / Atlantic City: Ventnor Beach

- 10 May 1906 / Wilkes-Barre: Giant’s Despair hillclimb

- 19 May 1906 / Cincinnati: Paddock Road hillclimb

- 24 May 1906 / Indianapolis: Glen Valley Hill hillclimb

- 26 May 1906 / Worchester: Dead Horse Hill hillclimb

- 12 July to 28 July 1906 / Glidden Tour: Buffalo to Bretton Woods

- 30 July 1906 / White Mountains: Crawford Notch hillclimb

- 31 July 1906 / White Mountains: Crawford Notch hillclimb

- 6 August 1906 / Newport: Sachuset Beach

- 3 September 1906 / Newark: Waverley Park

- 3 September 1906 / Atlantic City: Ventnor Beach

- 4 September 1906 / Atlantic City: Ventnor Beach

- 5 September 1906 / Atlantic City: Ventnor Beach

- 22 September 1906 / Long Island: Vanderbilt Cup American Elimination

- 3 October 1906 / Kansas City: Elm Ridge

- 6 October 1906 / Long Island: Vanderbilt Cup

- 13 October 1906 / Rochester: Dugdale Hill hillclimb

- 27 October 1906 / New York: Yonkers, Empire City

- 6 November 1906 / Newark: Waverley Park

- 6 November 1906 / New York: Yonkers, Empire City

- 29 November 1906 / Pawtucket: Stump Hill hillclimb

- 1 December 1906 / Los Angeles: Box Springs Canyon hillclimb

- 23 January 1907 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 24 January 1907 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 25January 1907 / Ormond-Daytona Tournament

- 30 May 1907 / Bridgeport: Sport Hill hillclimb

- 30 May 1907 / Wilkes-Barre: Giant’s Despair hillclimb

- 15 June 1907 / Cleveland: Stucky Hill hillclimb

11

11

- 10 July to 24 July 1907 / Glidden Tour: Cleveland to New York

- 5 August 1907 / Atlantic City: Ventnor Beach

- 6 August 1907 / Atlantic City: Ventnor Beach

- 7 August 1907 / Atlantic City: Ventnor Beach

- 9 and 10 August 1907 / New York: Brooklyn, Brighton Beach

- 6 September 1907 / New York: Morris Park

- 7 September 1907 / New York: Morris Park

- 14 September 1907 / Hartford: Albany Avenue hillclimb

- 27 September 1907 / New York: Morris Park

- 28 September 1907 / New York: Morris Park

So, exactly, what is the point of this listing of what are today, for the most part, events long forgotten?

First, this illustrates that even in 1908 there was a certain curiosity as to the listing and recording the results of the automobile contests of the day. This particular listing is among the more extensive such lists of the day.

Second, it suggests that a mere listing of events is not enough. The events must be populated with information. Usually lists of this sort have the winner of the event listed and perhaps a few other basic items of information. In the case of the vast majority of these events, there were several races that composed the racing program.

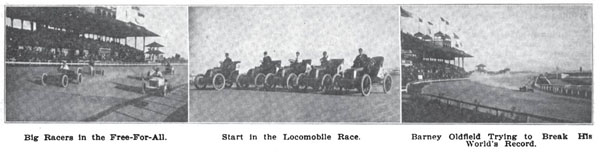

Consider, for example, the event that took place on 15 October 1904 at Cleveland’s Glenville Driving Park. Here is what the International Motor Cyclopaedia provides for this event:12

| Five Mile Event for 24-horsepower cars: | |

| 1st | Webb Jay, Peerless |

| 6 min 36 1/5 sec | |

| 2nd | George T. Turner, Peerless |

| Match Race for Ten Miles | |

| 1st | Barney Oldfield, Peerless Green Dragon |

| 9 min 17 1/5 sec | |

| 2nd | Earl Kiser, Winton Bullet No. 2 |

| 10 min 11.5 sec | |

| Five Mile Open Event, Stock Cars, Stripped, 35-horsepower and Under | |

| 1st | Bob Burman, Peerless |

| 5 min 37 3/5 sec | |

| 2nd | Joe Tracy, Royal |

| Five Mile Open Event, Handicap | |

| 1st | Webb Jay, White |

| 2nd | George E. Turner, Peerless |

Even in a short event that consisted of four races, a small headache can be noted: the middle initial for George Turner is given as both “T” and “E,” which could connote either a typo or that there were actually two George Turners in the meet.

Third, a listing of this sort may provide a framework for further work. By providing a date and a venue, one can considerably narrow one’s search for information about the individual events. There is, always, the problem of then finding that information. Fortunately, this has become somewhat easier, even if only in a relative sense, in recent years.

One should give praise where praise is certainly due and in this case Darren Galpin should get kudos for his dogged persistence in producing a work that should provide the framework for developing a record of American automobile racing during its formative years. Here is what Galpin provides for that same event at the Glenville Driving Park:13

Glenville Driving Track, Cleveland, OH

15th October 1904

| 5 miles - Open, under 24 hp | |||

| 1 | Webb Jay | White Steamer | 0:06:36.2, 45.43 mph |

| 2 | George Turner | Peerless | 5 laps |

| 2 | E.S. George | Peerless | 5 laps |

| 5 miles - Match Race, Standing Start | |||

| 1 | Barney Oldfield | Peerless "Green Dragon" | 0:04:44.2, 63.34 mph |

| 2 | Earl Kiser | Winton Bullet | 0:05:14.2 |

| 5 miles - Open | |||

| 1 | Burnham | Peerless | 0:05:37.6, 53.32 mph |

| 2 | Joe Tracy | Royal Tourist | 5 laps |

| 3 | Webb Jay | White Steamer | 5 laps |

| 5 miles - Match Race, Flying Start | |||

| 1 | Barney Oldfield | Peerless "Green Dragon" | 0:04:44.0, 63.38 mph |

| 2 | Earl Kiser | Winton Bullet | 5 laps |

| 5 miles - Open, Handicap | ||||

| 1 | Webb Jay | White Steamer | 5 laps | 0:20 Handicap |

| 2 | George Turner | Peerless | 5 laps | 0:20 Handicap |

| 3 | Joe Tracy | Royal Tourist | 5 laps | |

| 4 | Carl Fisher | Premier Comet | 5 laps | 0:00 Handicap |

| 5 | E.S. George | Peerless | 0:35 Handicap | |

| 10 miles - Match Race | |||

| 1 | Barney Oldfield | Peerless "Green Dragon" | 0:09:17.2, 64.61 mph |

| 2 | Earl Kiser | Winton Bullet | 0:10:01.2 |

Which could also be recorded this way:

Glenville Driving Track / Cleveland

15 October 1904

The focus of the Saturday meeting at the Glenville Driving Track was the match event between Barney Oldfield and Earl Kiser.

| Open race for touring cars up to under 24 horsepower | |

| Distance: Five laps of one mile track for five (5.0) miles | |

| 1st | Webb Jay |

| White Steamer | |

| 5 laps, 6 min 36 1/5 sec, 45.43 mph | |

| 2nd | George Turner |

| Peerless | |

| 5 laps | |

| 3rd | E.S. George |

| Peerless | |

| 5 laps | |

| Match Race, Standing Start, Oldfield versus Kiser | |

| Distance: Five laps of one mile track for five (5) miles | |

| 1st | Barney Oldfield |

| Peerless "Green Dragon" | |

| 5 laps, 4 min 44 1/5 sec, 63.34 mph | |

| 2nd | Earl Kiser |

| Winton Bullet No. 2 | |

| 5 laps, 5 min 14 1/5 sec | |

| 5 miles - Open | |

| 1st | Burnham |

| Peerless | |

| 0:05:37.6, 53.32 mph | |

| 2nd | Joe Tracy |

| Royal Tourist | |

| 5 laps | |

| 3rd | Webb Jay |

| White Steamer | |

| 5 laps |

| 5 miles - Match Race, Flying Start | |

| 1st | Barney Oldfield |

| Peerless "Green Dragon" | |

| 5 laps, 4 min 44 sec, 63.38 mph | |

| 2nd | Earl Kiser |

| Winton Bullet No. 2 | |

| 5 laps |

| 5 miles - Open, Handicap | |

| 1st | Webb Jay |

| White Steamer | |

| 5 laps, Handicap: 20 sec | |

| 2nd | George Turner |

| Peerless | |

| 5 laps, Handicap: 20 sec | |

| 3rd | Joe Tracy |

| Royal Tourist | |

| 5 laps | |

| 4th | Carl Fisher |

| Premier Comet | |

| 5 laps, Handicap: Scratch | |

| 5th | E.S. George |

| Peerless | |

| Handicap: 35 sec | |

| 10 miles - Match Race | |

| 1st | Barney Oldfield |

| Peerless "Green Dragon" | |

| 10 laps, 9 min 17 1/5 sec, 64.61 mph | |

| 2nd | Earl Kiser |

| Winton Bullet No. 2 | |

| 10 laps, 10 min 01 1/5 sec |

Using this approach, a more open format, to express that information relating to an event is the antithesis of the box score school of thought which dominates the way such information is presented, then as well as now. That it does not readily lend itself to being as easily processed as data as that using the box score format does is one reason to consider it as a better format should one wish to expand the information, data, that is found in its contents.

Galpin uses the information gleaned largely from newspaper reports as the basis for his work. With the increased availability of automotive journals of this era, there is now additional information for many of these events, especially with regard to contextual materials as well as the events themselves. Although in the work that he has made available Galpin more often than not does not provide references to his source material, he does have that information in his archives and this can be added as the material is developed.

It would seem to be a commonsensible suggestion to use the Galpin material as the basis for further work in developing a record of American racing for its first several decades. Adding references for the source material and expanding the information provided for each event as well as the contextual materials should provide a baseline for further work in this area.

At any rate, the plan is to begin digging into this era of automobile racing in the United States – with the odd excursion elsewhere – and presenting what can be found in upcoming editions. Unlike most efforts similar to this, there will be little of the usual, almost customary obsessing over the period machinery to the exclusion of almost everything else.

Book Review

The Winners Book: A Comprehensive Listing of Motor Racing Events 1895 – 2009, by James O’Keefe. Published by Racemaker Press (Boston), 2009; ISBN: 978-1-935240-02-0; 576 pages; $65.00.

Research is the raison d’être of historians. It is through research and the consideration of the results of that often laborious process that information undergoes the metamorphosis necessary for it to become knowledge. Historians build and reflect upon the fruits of the research that was conducted by others before them. Every historian has a shelf or two in his or her office of reference and research tools that forms the bedrock of his or her endeavors. For the automotive historian with an interest in automobile racing, among those books to be found on the office bookshelves might be such books as: The International Motor Racing Guide14 by Peter Higham; The History of America’s Speedways Past & Present15 by Allan Brown; The “Black Books”16 of the Formula 1 Register led by Dr. Paul Sheldon; Time and Two Seats17by Janos L. Wimpffen; Forty Years of Stock Car Racing18 by Greg Fielden; The Encyclopedia of Motor Sport19 edited by G.N. Georgano; and, The Autocourse History of the Grand Prix Car 1945-6520 by Doug Nye. Plus, of course, the various editions of Autocourse, as well as the usual serials such as Motor Sport, Road & Track, and all the usual other items that come readily to mind when something comes across one’s mind or if a question is posed.

Today, however, the internet has begun to replace out need for memory and digitization the need for shelves upon shelves of books. This is not all bad, given that the internet and the World Wide Web had provide more information – though, sadly, not that much knowledge – than previously imagined, along with the means to exchange thoughts and collaborate with others not possible in the past. Digitization has allowed resources such as newspapers and serials to be tapped from a distance without the difficulty of making the trek to the site where they could only be found in an earlier time. And, yet, there is something about the tactile sensation of holding and touching that font of information that surpasses easy explanation.

The book itself is a quality product. It is a first class production, one that publisher Dr. Joe Freeman can take great pride in. The book has the feel, the heft, the presence, if you will, of what one should expect of such a book, an expectation which, alas, is not always fulfilled. That is certainly not the case here. It would not be too much to say that the labor of love that O’Keefe produced is matched by the labor and love that Racemaker and Freeman poured into the physical aspects of the book.

In his introduction, James O’Keefe states that The Winners Book is intended to be both a “tool for serious research in the field of automobile racing history,” as well as being a book that can be enjoyed by the “auto racing enthusiast.” The Winners Book is exactly that – a book listing the winners of thousands of automobile races. Using the lists he began compiling of race results many decades ago, O’Keefe provides the reader with the following basic information for each event listed: the date, the name of the race (if there was one), the track or city, the number of laps, miles, the name of the winner, the car, the time, the average speed, and a note where applicable. This bare bones approach allows an amazing number of races to be packed into the book, something in the neighbor of twenty thousand plus entries.

The layout of the book is straight-forward, being divided into nine chapters, each covering a type of racing as defined by O’Keefe. The first chapter covers Grand Prix, Formula 1, and other “major races.” The second chapter is entitled “American Championship Races”; the third is “Major National Formula Races”; the fourth is “Second Rank Formula Races”; the fifth is “Third Rank Formula Races”; the sixth is “Sports Cars”; the seventh is “Stock Cars”; the eighth is “Trans-Am, IROC, and Touring Cars”; and, the ninth is “Motorcycles.” To collect all this information and then populate a database with it is a formidable task, one that few could probably even begin to imagine doing.

As is the case with each of the following chapters, the first chapter begins with a brief introduction to the type of events being covered, followed by listing of the relevant champions and championships, along with the broad specifications for the various formulae used. Then, as mentioned above, there follows the listings of race after race arranged chronologically by category. There are end notes when warranted, a very nice surprise given their scarcity in such publications. Although the type is, out of necessity, rather small, it is surprisingly easy to read, even for those with rather aged eyeballs.

It almost seems churlish to point out any of the inevitable errors that cannot help but creep into an enterprise of this magnitude. Indeed, I found fewer typos than one would expect given the thousands upon thousands of opportunities for them to find their way into such a work. This is a sign of good editing and an attention to detail of the sort that distinguishes Racemaker and a few other publishers from the pack, if you will. Most of what I will be pointing out are probably quibbles to some, but are, for the most part, related as much to the inevitable issues related to the layout chosen than to the scholarship involved.

My only quibble with the first chapter, which covers Grand Prix, Formula 1, and “other major races,” is that on page three, under “Champions,” O’Keefe has the entry “FIA Formula 1 Drivers” beginning with the 1950 season and continuing uninterrupted until the last entry, 2009. From its inaugural season, 1950, until the final season in 1980 it was the Championnat du Monde des Conducteurs or literally the “World Championship for Drivers.” Beginning with the 1981 season it was the “FIA Formula 1 World Championship.” The “1950 Championship” was terminated during 1980 and the new championship created for the following season, 1981. Then again, why should we expect O’Keefe to get it correct when no one else does? Indeed, even among those who consider themselves “purists” or “enthusiasts” there is still denial of this fact. However, if this is intended to be a reference work, such matters should be dealt with in some manner.

Chapter Two, “American Championship Races,” gets a Gold Star for beginning the listing of the American Automobile Association (AAA) National Champions with the 1916 season and rightfully giving Gaston Chevrolet recognition as the 1920 national champion. The absence of the 1905 “A.A.A. National Motor Car Championship” is noteworthy, this very issue being a point of discussion between myself and the publisher, Dr. Joe Freeman, at the annual Society of Automotive Historians awards banquet in October 2010 at Hershey, Pennsylvania. Dr. Freeman and Mr. O’Keefe were not completely convinced of the existence of the championship. There may now be adequate reason21 for them to include this championship in the inevitable updates to the book. This might also allow their inclusion in the listing of 1905 winners.

Continuing with chapter two, on page 50, the list of “USAC Silver Crown” champions begins with the 1971 season and George Snider. Not until the 1981 season did the “USAC Silver Crown Championship” come into being.22 From the 1971 to 1980 seasons, these events were known as the “Championship Dirt Car Series.” The results of this championship begins on page 131 under the heading “USAC Silver Crown Championship Results (1971-2009).” Granted, perhaps this was merely a name change to an existing championship, but it would take little effort to make a note of that fact. The United States Auto Club “Gold Crown Championship” is not mentioned, but that is probably just as well in some ways, given that there were only a few seasons where the International 500 Mile Sweepstakes – the “Indianapolis 500” – race was not the only event in the “championship.” It should be noted that most of the events listed from the 1904 season – which is where O’Keefe begins his listing – through the next several seasons are only those of any length, generally fifty or one hundred miles being the minimum. This, of course, leaves out many events considered noteworthy in the day, but the very number of these races is rather large and one needs to draw the line somewhere as O’Keefe points out.

Then, there is the 1946 season. On page 104, O’Keefe lists six events for the 1946 National Championship. What is omitted are the other seventy-odd events that were also part of the 1946 championship. The six events listed were all run to the rules governing Championship cars that season, which were simply those of the Formule Internationale of the Association Internationale des Automobile Clubs Reconnus and its Commission Sportive Internationale that came into effect with the 1938 season. The other events were run using rules for the “Big Car” class, better known today as “Sprint Cars,” which differed in a number of ways from the Championship “Big Cars.” It should be noted that other than a few, select series, O’Keefe omits any listing of Sprint Car events, for the very good reasons that the number of events would be almost overwhelming as well as simply attempting to discover all those events would be an exhausting task in and of itself.

Chapter Three, “Major National Formula Races,” covers the various championships “Down Under” as well in South Africa and Britain he considers to be major national series run to a racing formula of some sort. It also includes the “North American Formula A” championship that ran from 1968 until 1976. O’Keefe begins what was originally entitled the “Continental Championship” of the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) with the 1968 season and does not include the inaugural 1967 season since the Formula A in effect that season only mirrored the current Formula 1 and did not include the five-litre stock block option that was introduced for the following season, 1968. He does note that it became “Formula 5000” in North America in 1971 bringing it into alignment with the European nomenclature. O’Keefe does, interestingly enough, break out the North American Formula A and Formula 5000 results.

In Chapter Three, O’Keefe has a short list of “North American Formula Libre Results (1958-1963)” on page 184 that deserves attention, given that there is more to these than meets the eye. The 1958 and 1959 events held at Watkins Glen were part of the United States Auto Club Road Racing Championships in their respective seasons. The “formula libre”23 events listed for 1962, at Bossier City, Louisiana (Hilltop Raceway) and Clermont, Indiana (Indianapolis Raceway Park) were also events in the 1962 USAC Road Racing Championship. It should be noted that only the unofficial “overall” winner is listed, since each of the events was held in two parts, that is, two separate points-awarding races rather than as heats determining the overall winner. In fact, at IRP, the listing of winners should be corrected to list Roger Penske and Hap Sharp, respectively, as those winning the two races that comprised the “Hoosier Grand Prix,” Jim Hall being the “winner” only when the two separate and distinct points races are combined: which is not how USAC did business. As for the Bossier City event, Gurney won the two events or heats of the “Pipeline 200” and, therefore, actually won two events as far as the record book is concerned.

All this leads us to Chapter Six, “Sports Cars,” and the USAC Road Racing Championship (RRC), of course. On pages 296 and 343-344, there is a listing provided by O’Keefe of the “USRRC SCCA (Drivers)” championship and the results of that series (1963-1968). There is no mention of the USAC RRC on page 296, but there is a listing of events entitled “American Sports Car (USAC) Results (1958-1962)” on page 343, which precedes the listing of events for the SCCA United States Road Racing Championship (USRRC). The USAC RRC was held from 1958 until 1962, the pioneering series for professional road racing in the United States. The 1958 listing for USAC road races lists only two of the five championship events held that season; the other three were held at Lime Rock and Marlboro, 7 and 21 September respectively, in addition to the Watkins Glen event already mentioned. The discussion for the listing for the 1959 USAC RRC events is worthy of its own lengthy, confusing, and confounding discussion, but suffice it to say that several of the events had “heats” that awarded points and that, as mentioned, any “overall” winner is the invention of journalistic imagination. It should be noted that several of the events were “formula libre” in that cars from the USAC Midget ranks were included in the entry lists, even proving very successful in several instances, the most celebrated being the case of Rodger Ward at Lime Rock in July.

The 1960 USAC RRC round at Laguna Seca was run in two “heats,” with Stirling Moss winning both of them, giving Moss two wins in the record book rather than the “overall” win noted. In 1961, the RRC rounds at Clermont (IRP), Castle Rock (Continental Divide Raceway), and Laguna Seca were all run in two parts, O’Keefe once again recording only the “overall” winner. At IRP, for instance, Lloyd Rudy won the first race and Augie Pabst the second; Castle Rock saw Ken Miles win the first race and Bob Holbert the second race; and, Moss won both “heats” once again at Laguna Seca. Two of the 1962 RRC events have already been mentioned, Bossier City and IRP, but the “Northwest Grand Prix” at Kent and the “Pacific Grand Prix” at Laguna Seca were both two-part affairs, Dan Gurney winning both “heats” at Kent and although Roger Penske is listed as the “overall” winner at Laguna Seca, Dan Gurney won the first race and Lloyd Ruby the second race.

To return to Chapter Three for a moment: On page 186, O’Keefe has a listing for “USAC Formula 5000/Champ Car Results (1971).” This was intended to be one of several events that were to be a revival of the USAC Road Racing Championship which ended in 1962 – or 1963 according to whom one wishes to believe. In this case, O’Keefe reverses himself and lists the winners of both of the “heats” rather than simply listing the “overall” winner.

Chapter Seven, “Stock Cars,” is yet another witches brew of events and series that O’Keefe plunges into, once providing the occasion head-scratching entry. On page 400, “NASCAR Stock Car Results (1949-1971),” which really means the Grand National Division as is reminded on a note found on page 473, begins with the 1949 season, but only lists three events of the eight championship events held that season, even failing to mention the inaugural “Strictly Stock” event at Charlotte. For what is intended as a reference work to omit such events is very curious, indeed. It is no better for 1950, there being only six events listed of the 19 championship events held that season. Nor 1951, only nine of 41 championship events being listed. This is a consistent and curious decision made by O’Keefe for each of the Grand National seasons until 1971. To simply drop the other events without any explanation is one thing, to knowingly present incomplete information in a reference work is quite another. This seems such as odd, even quirky, omission for O’Keefe to make. One hopes that this is corrected in the inevitable future, revised editions.24

It strikes as curious that the photograph on the title page for Chapter Nine, “Motorcycles,” is that of Ralph Hepburn sitting at the wheel of a race car. I must admit that this literally stopped me in my tracks the first time I scanned the book. It seemed so odd, almost incomprehensible at the moment – and still does. Only the champions and events in the 500cc class of the FIM world championship are listed. The various 350cc, 250cc, 125cc, sidecar, and other classes are absent in this book. Nor should one expect to find a listing of the AMA champions or events. One does find, however, on pages 549-551 a listing of “American Motorcycle Results (1912-1941)” which simply piques the interest, of course. I am sure the few realize that in the aftermath of the “American Grand Prize” and Vanderbilt Cup races decamping from Savannah after 1911 that they were replaced by motorcycle races in the years immediately following their departure. Few also seem to realize the there were motorcycle events on the planked board tracks that seemed to proliferate on the American scene beginning with the 1915 season. Or that motorcycles, motorcycle racing, and Florida – Jacksonville and then Daytona Beach, have a long history.

Keep in mind that no one said ever that this was easy. It is this treading where even the angels fear to venture that makes this effort by O’Keefe so worthwhile. He is a far braver and more dedicated man than I will ever be in presenting such a work. Whatever quibbles or thoughts that I have presented here regarding this incredible work by O’Keefe and Racemaker Press probably address all of maybe one percent of the information found in this book. While one might quibble as to whether it is “DePalma” or “De Palma” – he seemed to use both – and such other very minor points, that is also one of the inevitable results of such a book. Always keep in mind that this book is subtitled “Comprehensive” and not “Complete.” There is a huge difference between the two and it succeeds quite well in attempting the former.

Bravo to O’Keefe and Dr. Joe Freeman of Racemaker Press for The Winners Book.

Further (Disjointed) Thoughts on History

It is said that journalists provide us with the “first draft of history.” This is certainly the case for modern history. By providing chronicles of the contemporary scene, journalists capture the moment, allowing the events that are unfolding to be seen through the eyes in the midst of the present without the benefit of the future. It is this focus on the here-and-now that gives journalism its value to the historians who follow in its wake years later.

That the history of automobile racing is in the hands of journalists is quite simple: the automotive historians have long ceded, literally, the narrative and the field to the journalists. It seems that, for the most part, the realm of what can be considered “sports history” has long been literally the home turf for generations of journalists and freelance writers, with very few historians from the academic side of the consideration of the past wandering into this broad field of endeavor. The number of books on the history of automobile racing written by a historian with an academic affiliation or even someone with a degree in an academic field involving the study of history and historiography would scarcely fill a shelf or two in even a modest library or collection.

That there are those journalists and freelancers who have mastered those skills necessary for the writing of history we should be very grateful. It has been observed that historians are made, not born. The work of several non-academic writers in the field of automotive competition rivals that of those dwelling within the hallowed halls of academe.

There is reason to question as to why having the history of automobile competition in the hands, literally as well as figuratively, of non-historians. After all, this has been the case for decade after decade after decade with scarcely a hint of protest as to the situation in all that time. It should be clear that the issue rests less with the journalists and freelancers, who, after all, stepped up and filled a void that would otherwise have continued to exist, than with the historians. It is, as is usually the case, not all that simple and straight-forward.

It should be offered that the “history” of automobile racing is, perhaps, more a case of there being a number of “histories” that often overlap, complement, and are parallel to one another. To study the history of automotive competition solely in the context of its time would be the likely approach by the historian. To study or consider those same events, but either in the context of the present or as seen from the present is the general inclination for the journalist, whose purpose is quite different than that of the historian. W.G. Sebald suggests this about another relationship: “Men and animals regard each other across a gulf of mutual incomprehension.”25 Although journalists and historians often study the same material, the same events, they do so with and from very different perspectives. It can be suggested that journalists and historians often do observe each other across “a gulf of mutual incomprehension.”

L.P. Hartley observed that, “The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there.”26 To view the past on its own terms, to develop a sense of “historical empathy,” to examine and consider the past to discover as much as possible as to nature of those events is the broadly stated goal of the historian. The historian accepts that “historical truth” is an elusive idea. As Gordon Craig put it, “What we consider as such [historical truth] is only an estimation, based upon what the best available evidence tells us. It must constantly be tested against new information and new interpretations that appear, however implausible they may be, or it will lose its vitality and degenerate into dogma or shibboleth.”27

Whereas the historian will examine the past with few, if any, references to the present, the journalist by the very nature of the worldview that is part and parcel of their craft find it difficult not to relate the past, that is history, to the present and attempt to find ways to make it “relevant” and to discover “lessons” from the past. The historian does not view the past in quite the same way, realizing that while there may be general cycles or patterns to be discerned from the study of history, that does not necessarily transfer to be a sure and study guide to the future.

Then, of course, there is the real reason that automobile racing history has the attention of a number of folks: money.

Granted, there is probably not a great deal of money to made by more than a handful writing about the history of automobile racing history. It could be suggested that it is the use of that history in the commercial side of the interest in things past related to automobile racing has been accelerated in recent years thanks to the advent of the internet and the World Wide Web, along with the use of the bulletin boards, chat rooms, and fora that this technology allows. True, long before there was a means to communicate through the ether by the use of home computers, letters and telephone calls worked just fine for those seeking to enrich their financial well-being rather than enrich their intellects regarding the use of the history of automotive competition.

Where once an old racing car was simply an old racing car, of little use or much value to anyone except for a very small handful of exceptional machines, most of which found their way to a few museums or collections. At some point, those wishing to create new markets discovered that in addition to the sale of used – “previously-owned” – passenger or road cars that were either scarce, desirable or actually rare for handsome prices soon realized that there might be a similar market for old racing cars.

It is possible that the creation of this market and the development of the various vintage or historic racing events and series are unrelated, but one seems to doubt that such serendipity was an scarcely unintended consequence or factor. Where there is a will to make money, there will be a means devised to do so, even at the expense, literally, of changing what was once a generally harmless, even slightly silly, pursuit into yet another money machine.

The magic word is “provenance.”

Provenance is, of course, roughly defined as the history of ownership of a valued object or work. It is “provenance” that makes the numbers on the financial statement swell. It is provenance that gives the old racing car its value in terms of cold, hard cash. It is provenance that tilts sentiment into the slippery slope of being one with Walter Mitty, of wishing to share the same space as a bygone hero did while on the track. Of playing well for such an opportunity to someone quite willing to take one’s money for such a privilege.

Once upon a time, people found that while an old racing car in reasonable condition may not be of much use in any contemporary competitions, that others with old racing cars might used to take the track to have, well, the fun and enjoyment of bashing about the track in such a car as it was once intended to do. The desire to restore and use old cars is one that has been around for many years, most doing so for their own enjoyment, only a few doing so on a commercial basis. That is, before The Collectors and the associated “Gordon Gekko” types arrived. That this dead horse has already been beaten to a pulp any number of times allows the discussion to move along to other topics lest one become distracted.

There are several contemporary magazines that provide some level of attention to the history of automobile racing in their content. Motor Sport is the oldest, of course, and two of the others that I am familiar with are Vintage Motorsport and Vintage Racecar Journal. There are others, of course, but I will confine my remarks to the three I am most familiar with, being a subscriber to all three. All three provide articles on topics that relate to racing history in the front and often provide coverage of what are called vintage or historic racing events in the back of the magazine. The Vintage Motorsport Annual is provided to subscribers as part of the subscription, otherwise one must forfeit the cover price of an astounding $24.95 for the privilege of having a compilation of photographs of the various vintage racing events, concours, and festivals conducted by the seemingly numerous organizations that support these events. To name a few whose events appear in the 2011 season: Classic Sports Racing Group, General Racing Ltd., Historic Grand Prix, Historic Motor Sports Association, Sportscar Vintage Racing Association, Vintage Auto Racing Association of Canada, Vintage Sports Car Club of America, and Vintage Sports Car Drivers Association.

Granted, there is nothing wrong with fixing up an old racing car so that you can once again place it in its former element, the race track, allowing one the personal enjoyment of simply having done so, either on your own or as part of a team. That this should be enough is too often not the case. The thinking is that race cars are made to be raced. Therefore, one need only find the organization either nearest you or more compatible with your desires to be able to take to the track in your lovingly restored old race car. Not to simply tool around, of course, to race.

Which circles us back to, naturally, money, provenance, and history.

A recent issue of Vintage Motorsport28 – which quite modestly proclaims itself as “The Journal of Motor Racing History” it should be noted – created something of a tempest in a teapot when the coverage29 of an event hosted by the Sportscar Vintage Racing Association in October 2010, at Road Atlanta celebrating its thirtieth anniversary, selected the McLaren M8F owned by Scott Hughes as its “Pick of the Litter” for the event. The McLaren M8F was presented as the one that was campaigned by Peter Revson during the 1971 season when he won the Canadian – American Challenge Cup series. That claim led to the aforementioned tempest in the proverbial teapot.

As it turns out, the McLaren-produced M8F chassis used by Revson that season – ‘M8F/1’ – was sold the following year, 1972, to Gregg Young for François Cevert to drive, and, in turn, was sold to the Commander Motor Homes team for Bobby Brown the following year, 1973. After various owners, it found its way to the Netherlands where it now resides in the Louwman Museum at The Hague. The “McLaren” being campaigned by Hughes in the same color scheme – papaya with blue wing and accents and number “7” – as used by Revson in 1971 was, indeed, once a part of the Commander Motor Homes team, but it was built up from spare parts by the team mechanics.

The resulting uproar was led by Tom Shultz, the track historian at Road America, and Peter Revson’s sister, Jennifer. The entire affair is covered quite well in a thread30 on The Nostalgia Forum at autosport.com entitled “‘Vintage Motorsport’ magazine.” I will, therefore, spare you the recounting of a blow-by-blow account of the affair. In the end, the editor of Vintage Motorsport, Randy Riggs, agreed to publish a correction in the next issue and is apparently unhappy with those who provided the information. So, the record will be set straight and, well, then what?

In the thread on “TNF,” several cautioned against letting their emotions get the best of them. As Doug Nye stated, “It's only an obsolescent racing car after all.” This did not seem to be all that well-received, but it did not differ all that greatly from the thoughts I was having regarding the affair. Certainly, there is the issue of Hughes stretching the truth – provenance rearing its head – more than a bit regarding the McLaren he must have shelled out more than a few dollars to purchase and then maintain. But, to The Untrained Eye, it looks almost exactly as the actual Revson McLaren did in 1971. That is enough, to be honest, for those among hoi polloi to be happy, given that is as close as they will probably be able to get to such a machine. From what seems to be written about the machine itself, the Hughes McLaren is very nicely turned out and well-prepared. We have now, of course, begun to thread on very thin ground.

Doubtless, the provenance and the value of the McLaren are related to those who have an interest in such things. Misrepresenting something for what it is not so as to increase its value and, thereby, separate more money from the one wishing to purchase it is, unfortunately, not an unknown occurrence. Given the available expertise on such matters as the McLaren in question, it does make one ponder why Hughes would make such a claim in the first place. It is also worthconsidering that having the McLaren examined by those who are the experts in such matters and then the verdict being that it was not built by McLaren Cars, but had a tub indicating that it was most likely either a production item built by Trojan or the one built up by the Commander Motor Homes team in 1973.

Again, we are left thinking, So?

It is this less a matter of automotive history and more a matter of, well, provenance and, yes, money? Perhaps. More than likely it is a bit of both, of course. Just as those with coronary problems tend to build up bypasses over time, so has Clio when it comes to automotive competition history. There has evolved something akin to an informal “Baker Street Irregulars” who attend to the various mysteries of provenance and other aspects of automobile racing history. Relatively few have any formal training in history, but many bring years of experience to the table and provide subject matter expertise on a broad range of topics. Along with those journalists staking claims to being “automobile racing historians,” these are those who have claimed the field from those who actually historians. This is scarcely unique, given that several other topic areas in the history field that the historians tend to be vastly outnumbered by the journalists and non-historians.

It is noteworthy that the issue of the Hughes McLaren was exactly that, an issue relating to a car. Indeed, once one begins to examine what actually interests those non-historians interested in the “history” of automobile it becomes clear that it is the machinery, the technical tidbits, the physical objects in the form of racing cars that generally attracts and holds their attention. The cars are the stars, their history, their provenance – real or imagined, being the attraction. While this is certainly understandable, there being good reason for it being called “automobile” racing, this also tends to overshadow the other aspects of racing, to what extent being, naturally, a matter of opinion according to which side of the fence you are on.

There is certainly truth in an oft-heard comment that historians tend to take the fun out of things, especially those who delve into the murky waters, the miasma that is sports history. However, that is a tale for another time, when the discussion will continue….

Noted in Passing & Other Observations

National Speed Sport News

The 23 March 2011 issue of the National Speed Sport News signaled the end of an era. This marked the last issue of the racing tabloid to be printed. The NSSN will continue to exist as a Web site, but that will not be the same. Corinne Economaki, daughter of long-time publisher and former owner Chris Economaki, finally wielded to the inevitable and pulled the plug when the economy and the resulting lack of available financing made printing and distributing the weekly simply an operation that could no longer be supported.

Beginning as a special feature of the Bergen (New Jersey) Herald, first appearing on 16 August 1934 as the National Auto Racing News, one of the teenagers hawking first the racing supplement of the Herald and then a writer when it began being published as a tabloid, was Chris Economaki. Beginning with first hawking the paper at the Ho-Ho-Kus Speedway to race-goers, writing articles on races, and then buying the paper not long after returning from military service in the Army during World War II, Chris Economaki and NSSN soon became an influential voice in the world of automobile racing. His weekly observations on the racing scene, “Editor’s Notebook” racing the original “Gas-O-Lines,” could make or break reputations, draw attention to or ignore trends that were happening. In addition to the NSSN, Economaki was also an announcer at various tracks over the years and then an on-air commentator in the pioneering days when network television first extended coverage to automobile racing in the Sixties.

The pages of NSSN were a potpourri of race reports, mentions of races, columns, reviews, and whatever else might find its way into what was as often as not as eccentric as it was eclectic, the latest on a race in Europe being crammed in among a series of reports on Midwest Sprint Car events. This was both its charm, value, and the reason NSSN was often a source of frustration for the historians. While it is possible that the only national recognition given to event might be its appearance in NSSN, what appeared there was often short, vague, and deficient in detail. To attempt to draw much from the pages of NSSN for events held during the Thirties and Forties can be an exercise in frustration and futility at times. However, it is often the only source that provides information for various events or series.

It must be noted that NSSN was first and foremost a national racing tabloid, although “national” was often synonymous with the Northeast and Big Car, Sprint Car, Midget, and other forms of American automobile racing. As the corps of stringers, correspondents, reporters, and contacts grew over the formative years, NSSN did become a truly national weekly racing publication. With its demise, losing National Speed Sport News means that yet another link to the past has been severed. Whatever its frustrations or shortcomings may have been, there was never an doubt that it was a work of – given that no other word really comes close – love.

Farewell, NSSN, you will be missed.

Mark Steigerwald

The longtime librarian and archivist of the International Motor Racing Research Center located at Watkins Glen, Mark Steigerwald, recently left the IMRRC for a position at Cornell University. Mark began working at the IMRRC as a summer intern while still in graduate school at Cornell. Over time, Mark’s work expanded to include most of the day-to-day administration of the IMRRC. This he handled in an exemplary manner. To many, Mark was one of the faces that became associated with the IMRRC, usually on hand to greet visitors to the center, provide help to researchers, represent the IMRRC at various functions, and generally handle the many major as well as mundane tasks that are the involved with the running of such an organization.

Mark was always ready to greet those who wandered into the center with a pleasant smile and a kind word. He was very helpful to me on my many voyages of discovery to the center. I, for one, cannot thank him enough for the many small kindnesses and favors that Mark made possible while I fumbling about the materials at the center doing research. Many a time Mark nudged me in the right direction when I got stumped.

Although Mark is now working elsewhere, there is a legacy that he leaves behind at the center of competence, knowledge, and good cheer. He will certainly be missed. Best wishes to Mark for continued success at his new position at Cornell.

Ochiltree Speedway Auto Races, 1916

31

31 32

32

An interesting thing that happens as one slogs through the grind of looking at newspapers or magazines for those elusive nuggets of information that will hopefully enlighten and/or connect a few dots is stumbling across items that often leave you hanging and then wondering about the rest of the story. The latest of these is the case regarding an advertisement I discovered regarding an event held at the Ochiltree Speedway in June 1916. This was an event that was completely new to me. Indeed, I was not even sure what part of Texas that Ochiltree was to found in, knowing that it had to be close to Beaver, Oklahoma – wherever that was.

I did find Beaver, Oklahoma. It is out in the Oklahoma Panhandle. I also discovered that while there is a Ochiltree County in the Texas Panhandle just south of Beaver, I could not find a town by that name. The county seat is Perryton, which, I thought at first was simply Ochiltree renamed, something not unknown in the United States. This was not the case, however.

Ochiltree was once a relatively thriving town in the northern part of the Texas Panhandle. When the lines of counties were redrawn in the late Nineteenth Century, in this case 1876, and Ochiltree became the county seat of what was now Ochiltree County in 1889, four years after it was the town was established. The town and county were named after William Beck Ochiltree, who was an official during the Texas Republic and later an officer in the Confederate army. As it turns out, there is still, apparently, an unincorporated community named Ochiltree, which is located about fifteen miles south of Perryton.

As was often the case in the matter of towns thriving or disappearing, it was that the railroad was built north of Ochiltree, through Perryton, that led to its demise. Once the railroad was in place, Ochiltree quickly disappeared, with Perryman, which was laid out by those building the railroad, becoming the county seat in 1919 and Ochiltree largely abandoned by 1920.33

The Ochiltree Speedway is not found in Allan Brown’s The History of America’s Speedways Past & Present.34 This was not that much of a surprise, having come across any number of tracks – and their particulars – that Brown does not have listed. I also began to wonder if there were other events after 1916. I did find a reference to another event in September 1916…

35

35

… but I was unable to discover any results for the races that may have been held.

One of the (several) reasons that the Ochiltree Speedway and its events caught my attention was that it continues to demonstrate the ubiquitous nature of American automobile racing, race tracks and events pooping up in often unlikely times and places, the Texas Panhandle of 1916 filling that bill. It also reinforces the notion that it is a fool’s mission to think that we will ever have a sense of “completeness” or “mission accomplished” when it comes to The Record of American Automobile Racing.

I should add that I have not been able to find a lake in the vicinity of what would be the former site of Ochiltree that could be the possible location of the Ochiltree Speedway. This is certainly one venue that could correctly be filed under the category “Lost Speedway.”

Notes

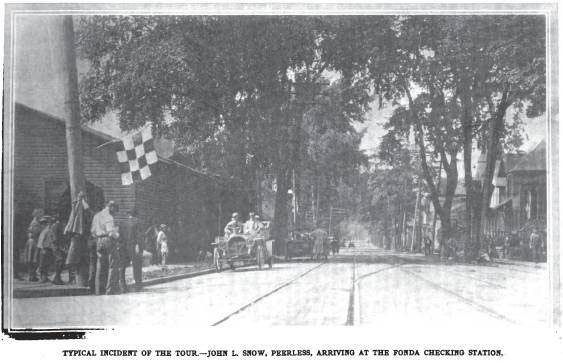

- “The Third Annual A.A.A. Tour,” The Automobile, 19 July 1906 (Volume XV No. 3), p. 67.

- International Motor Cyclopaedia, New York: E.E. Schwarzkoff, 1908, pp. 68-103.

- “The Long Island Automobile Club’s One Hundred Mile Endurance Test,” The Horseless Age, 24 April 1901, Volume 8, No. 4, p. 81.

- “The Brighton Beach Races,” The Horseless Age, 27 August 1902, Volume 10 No. 9, p. 212.

- “The Empire Track Races,” The Automobile Review and Automobile News, 15 October 1903, p. 158.

- “Brighton Beach Races,” The Horseless Age, 26 October 1904, Volume 14, No. 17, p. 431.

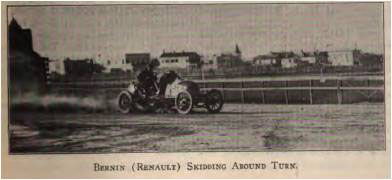

- “Successful Climb In Minneapolis,” The Automobile, 6 July 1905, Volume XIII No. 1, p. 25.

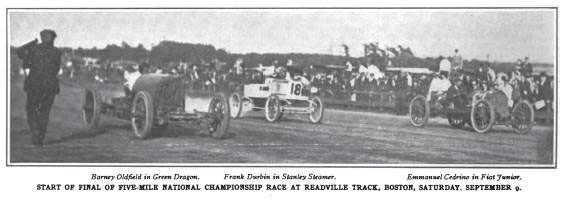

- “Good Racing at Readville Track,” The Automobile, 14 September 1905, Volume XIII No. 11, p. 296.

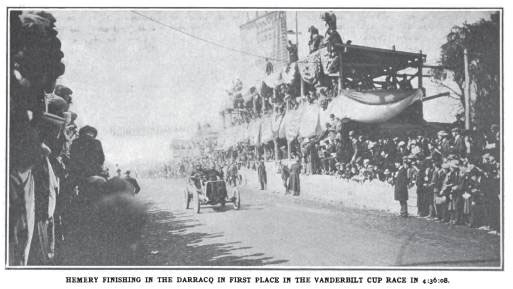

- “France Wins the Vanderbilt Cup,” The Automobile, 19 October 1905, Volume XIII No. 16, p. 420.

- “How They Finished At Atlantic City,” The Automobile, 3 May 1906 (Volume XIV, No. 18), p. 724.

- “Next the Big Tour of the Year,” The Automobile, 8 July 1907 (Volume XXI, No. 2), p. 47.

- Ibid., p. 71.

- Darren Galpin, The GEL Motorsport Information Page, The History of Motorsport before World War I

- Peter Higham, The International Motor Racing Guide: A Complete Reference from Formula One to NASCAR, Second Edition, Phoenix: David Bull Publishing, 2003.

- Allan E. Brown, The History of America’s Speedways Past & Present, Third Edition, Comstock Park, Michigan: Allan E. Brown, 2003.

- A Record of Grand Prix and Voiturette Racing, Shipley, West Yorkshire: St. Leonard’s Press.

- Janos L. Wimpffen, Time and Two Seats: Five Decades of Long Distance Racing, Book I and Book II, Redmond: Motorsport Research Group, 1999.

- GregFielden, Forty Years of Stock Car Racing, four volumes, Pinehurst: Galfield Press.

- G.N. Georgano, editor, The Encyclopedia of Motor Sport, New York: The Viking Press, 1971.

- Doug Nye, The Autocourse History of the Grand Prix Car 1945-65, Richmond, Surrey: Hazleton Publishing, 1993.

- H. Donald Capps, “The 1905 National Automobile Racing Circuit and the National Motor Car Championship,” SAH Journal, January-February 2011 (Issue 249), pp. 6-7.

- “Silver Crown Series,” 1981 Season Yearbook, Indianapolis: United States Auto Club, 1982, p.56.

- It should be noted for the record that these were events that allowed the inclusion of cars conforming to the “Intercontinental Formula” specifications as adopted by the United States Auto Club for 1962.

- Racemaker Press indicates that revisions and updates to The Winners Book will be provided in a digital format in the future.

- Taken from a review by Roger Ebert of Secretariat, 6 October 2010.

- L.P. Hartley, The Go-Between, London: H. Hamilton, 1953.

- Gordon Craig, “The Devil in the Details,” The New York Review of Books, 19 September 1996.

- Vintage Motorsport, March/April 2011.

- Walt Pietrowicz and Lu Pietrowicz, “Express Service,” Vintage Motorsports, March/April 2011, pp. 120-122.

- autosport.com Nostalgia Forum.

- The Beaver Herald (Beaver, Oklahoma), 8 June 1916, Volume 30 No 1, p. 1.

- The Beaver Herald (Beaver, Oklahoma), 22 June 1916, Volume 30 No. 3, p. 5.

- More on Ochiltree County can be found at The Handbook of Texas Online, provided by the Texas State Historical Association.

- Allan E. Brown, The History of America’s Speedways Past & Present, Comstock Park, Michigan: Allan E. Brown.

- The Beaver Herald (Beaver, Oklahoma), 7 September 1916, p. 8.