1973 Indianapolis 500

Reviewing a golden Indy anniversary that's better not celebrated

Author

- Henri Greuter

Date

- May 16, 2023; updated May 4, 2024

Related articles

- 1948 Indianapolis 500 - The Indy 1948 what-if, by Henri Greuter

- 1964 Indianapolis 500 - Closing in on the truth, by Henri Greuter

- 1992 Indy 500 - An Indy record deliberately listed incorrectly, by Henri Greuter

- 1995 Indy 500 - Rough justice, but justice nonetheless, by Henri Greuter

- 1996 Indy 500 - The 239.260 car, by Henri Greuter

Who?Gordon Johncock What?Eagle-Offenhauser 7200 Where?Indianapolis When?1973 International 500 Mile Sweepstakes (May 30, 1973) |

|

Why?

This article is based on a story written for The Short Chute, the newsletter for the National Indy 500 Collectors Club. The Short Chute is published four times a year. Each edition contains a reflection on a year at Indy that is 25, 50, 75 or 100 years ago.

For the Chute's winter '22/23 edition, I was handed the assignment to cover the least popular year of all to look back upon since the year of publication of the original story (the Chute version) and this 8W article (2023) is the 1973 race's golden anniversary.

1973 is probably the least popular of all 500s, and among Indy fans it is the one year they like to forget about as soon as possible and as quickly as possible. Based on the headlines and main stories of the year, it is indeed an Indy edition that simply can not be rated positive in any way.

Nevertheless, when taking a deep dive into the stats and figures of this race, something does pop up. Something that may make you realise that in your eager to ignore and forget 1973 as much and as quick as possible you never noticed before. I felt the subject worthwhile for a larger audience on a platform like 8W.

So I took the original newsletter version of my manuscript and modified it for this purpose to present a rarely remembered detail about the 1973 events at IMS. I say 'events' on purpose, because calling it a race would be too positive!

About 1973

In the two years before we had seen a dramatic and unseen increase in lap speeds thanks to the application of aerodynamic aids, wings in particular, with the tyre war between Good Year and Firestone adding another factor. Pole speed had gone from 170+ in 1970 to 195+ in 1972, so in just two years' time! This increase was not only due to the introduction of wings. Apart from generating downforce, wings also caused drag that slowed the cars down on the way to their top speeds. This drag had to be overcome by more power. And more power was what the drivers got. In spades.

Ever since the arrival of the Ford V8 engines in 1963 there had been a rivalry between the very latest versions of the Ford and the Offy, with both engines eventually reduced in capacity in order to be turbocharged. Over the years, the advantages between these two engines (both of which can be credited as being among the pioneers of turbocharged engines in cars) shifted from one to another. In order to regain supremacy, boost levels on both engines went up and with it their power output. From 1971 on, however, Ford pulled out and left the development of their V8 to AJ Foyt and his engine people and facilities. The number of V8 users decreased and the Offy was used by an increasing number of teams that subsequently developed the fourbanger to remain competitive against AJ's engine. Due to its design (dating back to the early thirties and arguably even the mid-twenties!) and construction, the Offy could eventually withstand higher boost levels to outperform the Ford. Power figures became so shocking that they reached four-figure numbers. In 1973, rumours went flying about some 1200hp in qualifying trim and 900hp in race trim.

Spare a thought for this: the turbo Offy was producing almost the same amount of power as Penske's frightening 1973 Porsche 917-30 Can-Am monster. For this, the German engine needed almost twice the capacity and three times as many cylinders. The highest power output value for a turbo Offy I have ever seen printed was when All American Racers had one on the dyno. Something went wrong with the boost control and the dyno gave a reading of over 1400hp as a result. But the engine survived!

To some extent, 1973 became the pinnacle year for the venerable Offenhauser, the last descendant and representative of the work of Harry Miller and Leo Goossen. Certainly in qualifying trim, the latest variants inspired on their four-cylinder design of some forty years earlier were among the most powerful engines ever seen at Indianapolis. There is still some mystery about exactly how much power the 1994 Ilmor 265/E pushrod engine used in the factory Penskes had produced on Race Day. But the 265/E could be another contender for the distinction of the most powerful Race Day engine ever in Indy history, challenging what must have been the most powerful car in the 1973 race. Will we ever know which car was the most powerful in the three days of the 1973 race?

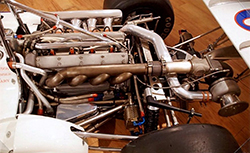

Seen here is an unrestricted boost version of the Offenhauser engine. This is a restored one fitted into what is generally believed to be the Eagle chassis that Bobby Unser used at Indy in 1972 when he took pole with a new track record. The type of inlet manifold seen here was the one most commonly used on engines in Eagle chassis. (photo HG)

A different type of inlet manifold for Offies was in existence too, seen here on an Eagle. This kind of manifold became more common after 1973, in particular on cars like the McLaren M16, Wildcats and Lightnings. (photo HG)

Combined with ever larger and better wings on improved chassis, the 200mph barrier at Indy was ready to crumble. And thus, practice started with high expectations but also with some reservations about what was to come. The first week saw quite a lot of rain too. Eventually the 200mph barrier failed to succumb, even though Johnny Rutherford in a works McLaren entry came close: he would be 0.22 seconds short.

Seen in the aftermath of May 2011, the 1974-winning car, the McLaren M16C-5 had left the IMS Museum's exhibition of winning cars and was ready to be prepared for a send off to the Goodwood Festival of Speed. That's why I saw it in an incomplete state. The photo is used here because M16C-5 has won more that only the 1974 race at Indy. The year before, being that year's 'lucky #7' M16C-5 had been used by Johnny Rutherford to win the pole position. Of course the car has been restored to its most glamorous configuration as the 1974 race winner. (photo HG)

Once qualifying was over the 1973 field was remarkable for the fact that perennial favorite AJ Foyt was almost the slowest qualifier which would have been for the first time in his career had he indeed been the slowest.

The Bob Riley-designed latest type 'Pet of SuperTex' definitely started its career rather poorly. However, assisted by rule changes valid from the next year on, the updated versions of this Coyote-Foyt became perennial favourites into the mid-seventies and one of the cars that would go on to define the era. (copyright Jim Edwards Collection, provided by Bill Ashby, used with permission)

And a technological first: for the first time ever, a car with twin turbochargers was in the field, powering a 1972 Eagle that was adapted to take the engine. This twin-turbo engine wasn't a pure-bred racing engine but a modified Chevy V8 stock-block with single camshaft and two valves per cylinder, pushrod-activated.

Seen here on a practice day in May 1973: Smokey Yunick's Twinturbo stock-block Chevy driven by Jerry Karl. (copyright Jim Edwards Collection, provided by Bill Ashby, used with permission)

The first weekend of qualifying was marred by the death of popular veteran Art Pollard who was killed in a high-speed crash on Pole Day. It was vindication for the worries expressed by the drivers during practice that with the current speeds things had perhaps become too dangerous. There certainly had been concerns among the drivers in the days before.

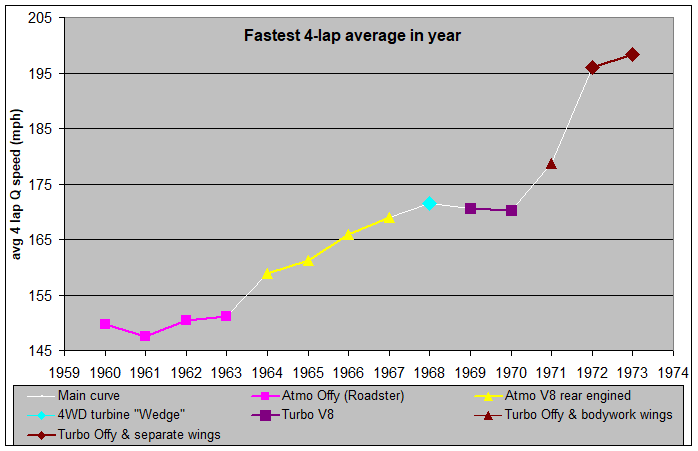

Graphic representation of the increase of speeds of the fastest qualifier at Indy over time, starting with the final years of the Offy roadster era which saw only few innovations resulting into more speed. This being followed by the arrival of lighter, more powerful rear-engined chassis and the early years of the tyre war between Goodyear and Firestone. Revolutionary technology driven to the edge gained pole in 1968 (4WD turbine-engined STP Lotus 56), followed by some stability again. But in 1971 the introduction of ever more powerful engines and wings allowed speed increments unseen before. The first year (1971) wings had to be part of the bodywork, one year later free-standing wings were permitted. For 1960 we see the speed as posted by Jim Hurtubise during qualifying, he was fastest in the field that year although not on the pole, which had gone to Eddie Sachs.

As for the race, general opinion is that the less is said about it the better. Let's respect that opinion. So here it in telegram style: First weather-delayed start aborted after violent crash by Salt Walther, causing injuries to him and people in the grandstands, rain making a restart impossible. Next day rain prevents any track action. Third day race starts early afternoon, with lap 59 seeing a violent crash for Swede Savage who miraculously survives. Race is red-flagged and a fire truck driving wrong way in pitlane hits a mechanic who is killed instantly. Race is restarted and red-flagged again because of rain after 133 laps, with incoming darkness ending all misery. Gordon Johncock declared the winner. Little more than a month later, Swede Savage dies in hospital having been infused with infected blood.

The aftermath of the horror of Race Day 1973 #1 visualised. This is part of what was left of the McLaren M16-3 in which Salt Walther had his near fatal wreck. Shown on display in the racing section of 'the Henry Ford' at Dearborn, MI. Even if he had to live on with some lasting results of this crash, 'Salt' was lucky to escape death that day. (photo HG)

Still, there is one aspect of the race that might be worth to have a better look at.

Some surprising 'what might have beens' unveiled after a closer look at that '500' that's best be forgotten

The race was (red-)flagged off after 133 laps (332.5 miles) with 11 cars still running, nine of them running Offy engines. There was still one Ford running and the 11th car was Smokey's Twin Turbo Chevy. The first two in were the lead lap, third place was two laps down, 9th place was 9 laps down, the 10th running car was 26 laps down and still 13 laps down on the already retired car currently in 10th place, the 11th running car (Smokey's Twin Turbo Chevy) was more than 100 laps down... it was classified 26th with 22 laps on the moment that the red flag was dropped.

The only two cars on the lead lap were Gordon Johncock and Bill Vukovich Jr (indeed, the son of the two-time winner of '53 and '54). Both men were driving Eagle-Offies.

The IMS Museum had/has a car said to be the 1973-winning car on display. But it is fitted with a narrow rear wing as they became mandatory from 1974. And although there were differences between how the car looked when it qualified (and so appeared on the familiar qualifying pictures) and the colours on Race Day, this wing error must have a reason, In this case: this isn't the real winner but a replica. (photo HG)

The third of the three Race Days in particular proved something that had not been proven sufficiently during practice and qualifying. Although the Offy reached its zenith in performance levels in 1973, it came with a price: reliability. Of the 26 Offy-powered cars that qualified, 17 cars retired from the race, 12 of them with engine-related issues when the red flag ended the on-going misery. Not that the Fords had done much better: under the ever-increasing levels of boost, reliability for the Ford engines became more of an issue. Only one of the six Ford-powered cars that qualified was still running and four retired with engine-related problems. And the singleton Twin Turbo Chevy with 22 laps done up to that moment, well, what to say about that? At least it was quite an achievement by the crew that after more that two hours of repairs in pitlane they got the car going again.

The Smokey Yunick Twin Turbo Chevy looked kind of neat for such an early xample of a V engine with twin turbochargers. This engine is built into a different chassis from the original Eagle chassis to create a replica of how the 1975 version of the car that did make the race looked like. (photo HG)

With the 1973 race advised to be forgotten ASAP, we should leave it at this point. But what if we don't do that? Accepting things as they are and looking into details, trends etcetera, is there something that does attract our attention? Well, yes, for me there was.

The most recent race with the least amount of finishers was 1966, with only seven cars flagged off from of what had effectively been a 22-car race after 11 cars had been wiped out in a starting accident. Which leads to a daring thought.

Given the retirement rate in the 1973 race, one might wonder how many cars would have made it to the end if the race had gone the full distance one way or another.

It can be argued that 1973 was actually a race with only 32 cars instead of 33 because when the race was finally started on Day 3 there were only 32 starters, Salt Walther being the lone casualty of the crash two days before. And you may actually wonder how many cars could have started the race if a restart had been possible right after the start crash on Day 1.

But for our review we will start with including the entire field.

After the failure of the anhedral-winged cars of 1972, both the original and modified versions, the Vel Parnelli superteam came with new cars for 1973. Seen here at IMS Museum during the Unser Expo in the summer of 2018, this was the Parnelli-Offy driven by Al Unser. Like his team mates Mario Andretti and Joe Leonard he retired well before the second red flag of the day, the one that mercifully ended the misery. (photo HG)

It is possible to do some very basic statistics with the data available and assume that the retirement figures up to lap 133 were a perfect average, suitable to correctly predict for what was to follow thereafter. Not that this can be the case but for the sake of simplicity, let's say it was.

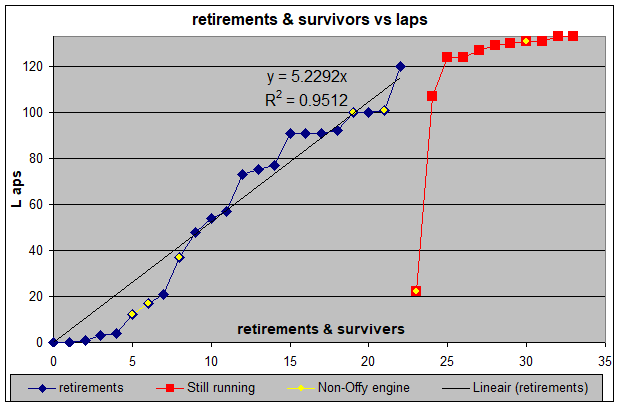

Presented are the cars in order of their retirement from the race (blue) and the cars still in the race (red) with the amount of laps driven by each car. A yellow center point stands for a car with a powerplant other than a four-cylinder Offy engine.

Using these data we see a shocking result if the reliability statistics as valid for up until lap 133 are followed. Allowing for some optimising of the obtained averages, it would have resulted in the fact that based on engine reliability, other car parts' reliability and the average of crashes per number of laps also remaining the same, the last car would have retired from the race somewhere between lap 172 and lap 184!

With all due respect for Smokey's crew efforts to get their car back into running condition and still be a runner at the moment of the red flag, the car was so far down in the field that it is difficult to maintain the car as a valid entry for the data to be analysed. Technically, it was still possible that the car would beat the odds to become the only car to make it to the finish but it is not very realistic. So I exclude the car for further data analysis as from here on.

Excluded for the statistics that follow is Mel Kenyon's #19 Eagle-Ford. But here is a picture of that car as it looked in April 2024. Good observers will notice the engine in the car being a normally aspirated Ford instead of the turbocharged one in used in 1973. A later owner of the car had the temperamental and sensitive Turbo Ford replaced with a specially prepared atmo Quadcam Ford for easy maintanance and servicing to enable him to have some good times with the car on track days himself. (photo HG)

So for the ten remaining cars, we were left with nine Offy-powered cars and a lone Ford. I am also rating that lone Ford as an outlier given some statistical proof for that as well. According to the stats valid for the Ford retirements, the lone remaining Ford runner Mel Kenyon should have had to call it a day between laps 115 and 124 but with him still running and flagged off after driving 131 laps he proved how wrong stats can be. Wrong enough to take him out of our further data analysis.

So by now we are left with nine survivors, and all of them were Offy-powered. That enables us to look into the details of the retired Offy-powered cars in order to see what kind of predictions we could make based on those statistics. For beginners, let's use the data of the 17 Offy-powered cars that had retired for whatever reason, be it related to the engine, the chassis or a crash.

Based on those data and maths, the 26th and final Offy-powered car would have retired for whatever reason somewhere around or in the window of laps 175 to 186. Granted, that is a small improvement over the data with the Ford and Chevy still incorporated.

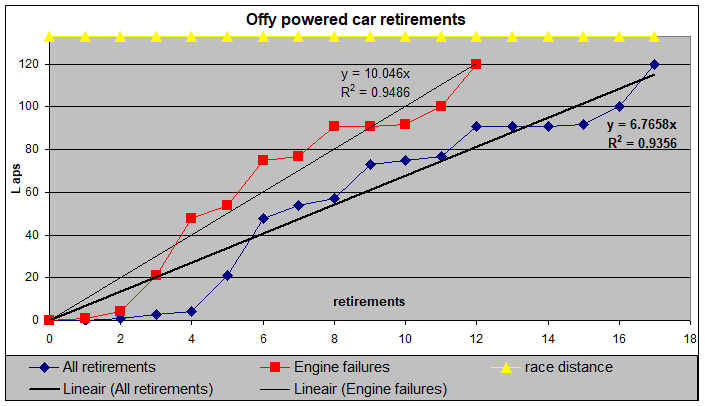

In blue all retirements for Offy powered cars, in red the engine failures within this population.

When we only consider the retirements related to Offy engines, thus effectively on engine reliability, the figures start become slightly better. The 12th and last Offy car that had retired from the race with an engine-related failure had done so after 120 laps. Based on the stats for the valid data that means that in order to reach a distance of 200 laps it would have required about 19.6 to 19.9 Offy-powered cars to make it. There had been 12 engine-related retirements already and there were still nine Offy-powered cars left in the race. This means that as long as these nine survivers would be struck by engine-related retirements alone, then at least one and maybe a second one would have made it to the finish. But there no single guarantee that the two cars on the lead lap (or red-flagged after 133 laps) would be among the two cars that could have made it to the end!

The car in which Bill Vukovich Jr finished second in 1973 was part of a display in the IMS Museum in 1994, and because of sad reasons. The Vukovich family had seen three generations racing in the 500, Bill Sr becoming a two-time winner in the mousegrey roadster but losing his life while on the way to win #3. Bill Jr's best result was second in 1973. His son Bill (Bill Vukovich III) was rookie of the year in 1988, raced three times at Indy but was killed in a sprint car race in November 1990. In the background is the yellow-orange Lola-Buick driven by Billy III in his final 500. This tribute at IMS Museum was created to honour the first family of which three generations raced in the 500 Miles, but only one of them survived his racing career. (photo HG)

As for the Offy retirements, even during the race itself a trend about these retirements was noticed. It was mentioned during the TV report that a large number of the retirements were because of broken conrod bolts in the Offy engines. Since this was believed to be a near standard part used on the majority of Offies, the commentators said that with the current rate of retirements it would become a question if there were any Offies left running at the finish!

Checking out a more detailed list of final results with reasons of retirements confirms this comment made during the TV report. Of the 12 engine-related retirements for Offy-powered cars more then half (7) were because of these failing conrod bolts. But these bolts weren't the Offy's only weak link. From the remaining five engine-related retirements, trouble had been piston-related with four of them.

Although not herited from the kind of Offies used in 1973, this is nevertheless an impression of the kind of hardware that was hidden within the crankcase and cylinder block of an Offy and what had to endure the tremendous power bursts from the combustion strokes. And also: why the engine vibrations of the engine were so massive. The piston shown is a Mahle-made piston used in a 44-degree valve-angle type Offy. When you take a close look at the slide rule in the picture you can read the bore of the piston: 112.5 mm. The weight of this piston is 1009 gram. On top: an 1:25 scale model of a 1975 type of turbocharged Offy, once part of a 1:25 AMT kit. (photo HG)

The connection rods on the turbo Offy were short and durable but contained a lot of beef to cope with the forces they had to transmit from piston to crankshaft. This one measures 209mm from top to bottom end, with 149mm between the centers of the bearings. The diameter of the crankshaft bearing is 58mm, the one for the piston wrist pin measures a little under 30mm. Including the connection bolts attached onto the rod, this one weighed in at 1259 gram. All of this means that each crankshaft throw had some 2.27kg attached onto it, reciprocating up and down with, eventually when at speed, more than 9000 rpm. (photo HG)

After showing these pictures the following comments seem appropriate. The 1973 race definitely doesn't represent the best of what Offies stood for and were known for. The reputation of the engine took a beating that year. Still, F1 fans in particular often look onto the Offy with some disdain and rate it as primitive. Primitive it may have been, but especially the turbocharged versions still permitted to run at unlimited boost levels (like in 1973) were absolutely formidable, true-to-the-word powerplants that deserved more credit outside the US than they generally get. Its massive power output was courtesy of tremendous fuel consumption figures, not in the least as the Offy ran on low-caloric-value methanol. So a direct comparison with the ultimate in power-producing turbocharged F1 four-cylinders, the 1986 BMW, is difficult. The BMW ran on toluene-based fuel blends and used high-tech engine management systems. The Offenhauser never used any of such equipment, so it remains a question what kind of performances the improved mid-70s versions of the Offy could have achieved at unlimited boost level, with an intercooler and high-tech engine management systems. Maybe outputs that were not that much higher than in 1973 due to the engine having reached the limits of survivable mechanical stress, but it might have produced its possible maximum power output perhaps much more fuel-efficient?

Back to the events of 1973. Nonetheless, given the circumstances on that Triple Day Race, the eventual end (red flag due to rain again) was a blessing in itself after all the misery. But it might well have been a blessing in disguise in many more ways. Had the race continued one way or another, how many of the 11 cars still running would have made it to the end? Would the statistics eventually have been correct in predicting the results and would we have seen less than a handful cars make it to the finish in conditions varying from anywhere near still healthy at speed or at much reduced speed in a contest of 'survival of the fittest'? Would we have seen all Offies and the remaining Ford retire prematurely and 'tail-end Charlie' Twin Turbo Chevy eventually pass all those retired cars and make it to the end as the lone survivor?

Just imagine such scenarios happening as a next episode in the story about Indy '73, after all that had happened already.

Or how about the following scenario? The following year's race (1974) was as perfect as it could get without a single memorable nasty incident of any kind. In the actual race we saw 12 cars flagged off with the eighth-place finisher 11 laps down. Anyway, a near perfect race on a weather-wise near perfect day as well.

Now imagine being at the Speedway on such a day with the first 133 laps of the race running without all those race-stopping accidents of 1973, but with the retirement rate we had in 1973. And then with those retirements continuing after 133 laps at the same rate... This would have led to the kind of results listed above. It certainly would have made a memorable race in Indy 500 history in its own special way.

Still, I think most people will agree that such an imaginary scenario on an otherwise perfect Race Day in 1973 would have been the preferred scenario instead of the nightmare that took place over three days' time.

So how poor was the 1973 race truly if it comes to reliability? For this, let's compare it with the other race lamented for its low number of race finishers, the infamous 1966 race. The '73 race ended after 133 laps with 11 cars still running, which makes a survival rate or 33.3% for the entire field. The 1966 field still contained 12 running cars that had made it to lap 133 for a slightly better 36.4% survival rate for the entire 33-car field.

When we look for the percentages for the 22 cars that took the restart in 1966 and got to lap 133 and further, then the 12 survivors make up for 54.5% of these 22 cars. For the record: using the same kind of statistics as used for the 1973 field on the entire 1966 field, the last car would have retired at around lap 155! If we apply the statistics for the 22-car field that took the restart that year, it would have taken 16.9 cars to reach the 200 laps, thus 7 survivors at 200 laps: exactly the number of cars that either received the chequered flag or were flagged off when the race ended.

Anyway, returning to 1973, it shall remain a mystery how many cars would have seen the chequered flag if the event had somehow gone the full distance. But after everything that happened until that rain-induced red flag after 133 laps I doubt whether many people really cared about that.

Sad as it was (following 1972, in which we had also seen a speed-related fatality), the 1973 race did result in some rule changes that made racing at Indy and in USAC generally safer. Although it came with an aspect that in hindsight proved much more questionable that it initially appeared as one of these effects was that one year after reaching the zenith of its performance capabilities, the venerable Offy was sent on its way to be phased out of Indycar racing.

And fortunately, Gordon Johncock, the winner of 'the race everyone wants to forget', won the 1982 race later on, the race that no-one will ever forget.

In May 1989, the IMS Museum got a visitor: the Penske PC10 used by Rick Mears in the race of 1982 and in which he was the loser behind Gordon Johncock in what would be the closest finish ever at the Speedway up until that moment. Since the Museum owns Johncock's winning car, they used the opportunity to put the cars in a position that resembled their finish of 1982. (Photo HG)

Coincidentally, this was also a race with an accident as soon as the the start flag was dropped. And, believe it or not, in yet another race with a start accident (1966), Gordon Johncock had a belated restart. But according Timing & Scoring his net time over the 500-mile distance (so all time at the pitlane being ignored) was faster than those of the three cars classified ahead of him!

In the mammoth 2011 IMS Museum exhibition where as many winning cars as possible were brought together we got to see the real 1973 winner, at that time in private hands. The chassis has even been reunited with the engine block that it used in those three days in May 1973. Once owned by the Brayton family, despite some appearances in the IMS Museum in recent years, the car is nowadays still privately owned. (Photo HG)

In fact, Gordon Johncock could have been the winner of three races red-flagged after a starting accident! But sadly, these very same three races share another feature apart from being red-flagged at the start due to a multi-car accident early on in the race, as 1966 (Chuck Rodee), 1973 (Art Pollard) and 1982 (Gordon Smiley) are years in which a driver got killed in an accident that took place on Pole Day. All facts and stats generally overlooked because of the fact that the less said and remembered about 1973, the better.

Gordon Johncock wrote several moments of history at Indy but there is one that few people are aware of, despite having nothing to do with 1973! Seen here in not the best of pictures is a Watson-Offy roadster. It was the car that Gordon raced in his first-ever Indy 500 in 1965. He finished the race in fifth position, the first Offy-powered car at the finish and the last driver that year to go the full distance of 500 miles. But since his car was front-engined, this result made Gordon the last driver ever in the history of the Indy 500 who followed his engine over the finish line when receiving the chequered flag. Every driver after Gordon in 1965 and ever since who crossed the finish line after 200 laps did so sitting ahead of their engine. Gordon however wasn't the last driver ever to see the chequered flag while driving a front-engined car. That honour went to Eddie Johnson who was flagged off in tenth place after 195 laps in the 1965 race. (Photo HG)

Finally, despite the fact that 1973 is said to be a year not to be remembered too intensely, one celebration ceremony has taken place in late April 2023 to commemorate the golden anniversary of a driver winning the race has taken place after all. Winners are presented the Borg Warner Trophy in Victory Lane but they are not permitted to keep it. Instead they receive a scaled replica version. The first of these versions was a cut-in-half upright version framed onto a walnut wooden plaque. From 1988 on, however, the winners received a full, free standing 46cm version named the 'Baby Borg'. Since 2013, the Borg Warner company started the tradition to hand drivers who are still alive such a new 'Baby Borg' version to commemorate the 50th anniversary of their Indy victory. It was reported that Gordon was presented such a 'Baby Borg' in late April 2023.

But then, if I rightfully give a well-deserved mention of a tribute to Gordon Johncock for his 1973 achievements, isn't it also appropriate to bring a salute after all to the other three men forever connected with the nightmarish Indianapolis 500 of 1973?

Art Pollard, Armando Teran and Swede Savage, may they rest in peace.

Bibliography and literature

Carl Hungness' Indianapolis 500 Yearbook 1973, several contributing authors, Carl Hungness Publishing, Speedway, IN (1973)

The Illustrated History of the Indianapolis 500 1911-1994, Jack C. Fox, Carl Hungness Publishing, Speedway, IN (1995)

Autocourse Official history of the Indianapolis 500 (second edition - fully revised and updated), Donald Davidson & Rick Shaffer, Icon Publishing Limited, 2013.

The Miller Dynasty, A Technical History of the Work of Harry A. Miller, His Associates, and His Successors, Mark Dees, The Hippodrome Publishing Co, Moorpark, CA (1981, 1994). Used was the second printing, the updated version published in 1994

Offenhauser, the Legendary Racing Engine and the Men Who Built It, Gordon White, Motorbooks International, Osceola WI (1996)

I consulted the Internet for verification of some details

Wikipedia: several themes

YouTube: 1973 Indy 500 race report as broadcasted by ABC television

Special thanks to Mr Brian Brown (Fort Wayne, IN) for providing valuable information regarding the situation about the fate of the winning car of 1973. Also thanks to Dr Tom Lucas (Speedway, IN) for providing more info about the current whereabouts of the 1973 winning car.

Also special thanks to Mr Bill Ashby (Brownsburg, IN) for providing images from the Collection of Mr Jim Edwards (Zionsville, IN) used in this piece.