Ferrari at Indianapolis: mutual love unanswered

1986: projects 034 and 637, mere blackmail tools?

Authors

- Henri Greuter, Arjan de Roos

Date

- May 22, 2013

Related articles

- March-Porsche 90P - The last oddball at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, by Henri Greuter

- March-Alfa Romeo 90CA - Fiasco Italo-Brittanico, by Henri Greuter

- The Race of Two Worlds - The 1958 "Monzanapolis" bash, by Darren Galpin

- Ferrari at Indianapolis, by Henri Greuter

- 1951: Ferrari and Indianapolis

- 1952: Ferrari at Indianapolis

- 1956: A 'hybrid' against one of Indy's most persistent jinxes

- 1958: At home against Indycars

- 1961-1968: of phantoms and enfants terribles

- 1971-1973: 'Meet my uncle Franco'

- 1975: A loud insect never leaving the chrysalis as was intended and hoped for…

- Intermezzo: Ferrari and turbocharging

- 2000-2007: It's Indy, Gino, but not as we know it

- Appendix: The cars

What?Ferrari 637 Where?Galleria Ferrari, Modena |

|

Why?

This chapter is an extended and updated version of the introduction chapter that is part of the 8W series covering the 1990 March 90CA-Alfa Romeo. I want to express my thanks to co-author Arjan de Roos for his share in this chapter.

Indycar and Indianapolis wasn't on the Ferrari agenda for a reasonable period of time, although we may wonder if it was ever out of Enzo Ferrari's mind. During his lifetime, his cars had won just about every major race in the world. Only Indianapolis was still missing.

In the early eighties, Enzo Ferrari wasn't very satisfied with what he saw in Formula One. On one side his cars weren't winning as often as he wanted. But mostly he was tired of fighting all the political battles with the upcoming Bernie Ecclestone and FISA president Balestre on the direction Formula One was going, the many rule changes and uncertainties posing a threat. Meanwhile, the US sales of Ferrari production cars had become a very important factor for his company.

At the time, however, Ferrari had limited racing exposure in North America: only two or three Grands Prix a year, and racing is promotion for Ferrari. (See Footnote 1 for another factor that may have promoted Ferrari road car sales.)

Then there was that life-long dream of his (and at his age it had become a very long-lived dream) to at last win Indianapolis. Here was a point in Ferrari history in which we saw the Old Man excel once again. “Why not create a car with which to compete in the popular CART series while at the same time possibly leave Formula 1. Let's see what “they” will do with the prospect of having no Ferrari in F1.” The project looked like an attractive option to pursue.

Expertise and experience were sought in the States. Competition director Piccinini went to see CART racing in July 1985 and had talks with the organisation. He took a good look at all the teams running in CART. Leo Mehl of Goodyear advised Jim Trueman's TrueSports as a strong partner. (The F1 Ferraris ran on Goodyear tyres, while Goodyear was the single tyre supplier in CART.) Mehl also made the first contact. “Would they be interested in doing something with Ferrari?” A month later Piero Lardi-Ferrari visited Jim Trueman, Steve Horne and Bobby Rahal at TrueSports. He invited them to come over to Maranello for further talks as well as to demonstrate their own car. At that time Adrian Newey was working as an engineer at TrueSports. Trueman and co tried to persuade Newey to design the Ferrari Indycar. Newey refused (since March had given him the job to become engineer at the Kraco CART team for 1986) and the project team had to look for other options.

Gustav Brunner was hired as a designer to Ferrari. One of his tasks would be to design the Indycar. As he had never designed an Indycar before Brunner visited several CART races and tests at the end of the season. In 1986 he even visited the Indy 500 with then Ferrari president Vittorio Ghidella. All in all signs that Ferrari was indeed quite serious about this project, it was more than a bluff.

In summer first news broke that Ferrari intended to race in Indycar. Of course Piccinini's visit hadn't gone unnoticed. While in the States Piccinini was asked to comment but he made it clear that the decision to enter was for the company directors and Ferrari had the intention to always race in F1. Then Enzo Ferrari issued a press statement: “The news concerning the possibility of Ferrari abandoning Formula One to race in the United States has a basis in fact. For some time at Ferrari there has been study of a program of participation at Indianapolis and in the CART championship. In the event that in Formula One the sporting and technical rules of the Concorde Agreement are not sufficiently guaranteed for three years the Ferrari team (in agreement with its suppliers and in support of its presence in the US) will put this program into effect.” Sensational news in the world of motor racing. Racing fans cheered for a possible Ferrari in CART, a series growing in (worldwide) popularity. Ferrari fans dreamed along for the Borg Warner trophy. Meanwhile, sceptics explained this new Ferrari bluff to all who would listen.

Piero Lardi-Ferrari was interviewed at the British Grand Prix: “If we carry on with Formula One, we probably would not do anything else. But we spoke of the possibility of racing CART to show that we will not necessarily be in F1 forever. We want to stay in it, but only if the technical regulations remain as they were scheduled originally. No changes. We have made huge investments in electronics, and we don't see why we should be penalized by a sudden change of rules. Nor do we think it valid to make changes in the interests of economy. F1 is the top level of the sport and should not be restricted in this way. If we do go to Indianapolis we would definitively build our own cars, but probably they would be run with some American involvement. At first we think the right engine would be the V8 being used by Lancia at present. After that we would build a new engine specifically for CART racing.”

So Ferrari already had an engine available coming close to being suitable for CART. For the Lancia Group C project Ferrari had built a turbocharged V8 with a capacity of 2599 cc, almost exactly the size permitted by CART. This V8, the 268 (the type registration 282C has also been used for it) has been described as an entirely new engine, although it was based on - and had parts in common with - the 3-litre production engine as used in the smaller V8-engined Ferraris, and had two turbochargers. Besides that, it was developed with Group C rules in mind. Fuel consumption rules permitted the use of about 55 litres of gasoline for every 100 km. By the way, eventually a 3-litre version of the engine was pressed into service. To say that this engine was suitable for use as a methanol-fuelled pure-bred engine seems to be a bit too optimistic, even though some valuable experience with a blown V8 racing engine was gained. Nevertheless, any serious Ferrari Indycar project most certainly required a V8 engine designed from scratch.

An early version of the Lancia LC2, the Ferrari V8-powered Group C car that ran without much success between 1983 and June 1986. This is one of the cars that raced in the 1983 Silverstone 1000kms. The picture doesn't show it very well but the most striking detail of the early LC2s was that they were rather narrow: 1.80m while 2m was the accepted maximum. (photo copyright Rich Harman, used with permission)

A late-version Lancia LC2. This car is pictured during a veteran car meeting that was part of the weekend of the Rolex 24 Hours of Daytona in 1999. The lower part of the bodywork had been widened and so was the track width. This was done to improve handling and also to keep the vacuum within the venturi tunnels a bit higher than on the narrow-track cars. (photo copyright HG)

The irony for the Group C engine was that Lancia left the world of endurance racing in the spring of 1986, after a couple races with little result: just about the time the new Ferrari CART engine was set to be built.

An detail that is unimportant for this story, but we'll give it to you for the sake of completeness, was that the 268/282C wasn't the first turbocharged Ferrari V8 used in competition. In 1979 the Italian Jolly Club developed a Group 5-spec version of the Ferrari 308 GTB fitted with a twin-turbocharged version of the V8. That engine was good for a reported 750hp and thus at least on paper could be a worry for the Porsche 935s that were still in operation. These were about the most powerful cars still used in long distance racing at the time.

This picture taken during the introduction of the Jolly Club 308 GTB Turbo appeared in an edition of Dutch magazine Autorensport, released in February 1979. This does prove that this particular car was very likely the first-ever turbocharged Ferrari racing car to appear in public, even if its first race would be some time later. (photo copyrights unknown, reproduced from Autorensport magazine, edition Februari 1979)

The 308 GTB Turbo was entered for an event just once during 1979 but didn't show up. Some more entries were made in 1980 and especially 1981. Without factory support the car could never be developed properly, so it gained few race results. It was fast, won a number of very respectable qualifying positions but often the car failed to start after yet another decent qualifying result. The Jolly Club eventually fielded Group 5 Lancia Beta Monte Carlo Turbos instead and these cars played a vital role in the successful defence of Lancia's World Championship constructors title in 1981.

The Jolly Club Group 5 308 seen at Silverstone during the 6-hour race of that year. In this kind of weather conditions it must have been quite a challenge to drive this powerful car. It had qualified 6th fastest yet failed to finish due to a gearbox problem. A coincidental detail: the chassis number of this car has been listed as 18935... (photo copyright Ralph Colmar, used with permission)

The most important contribution of the Jolly Club Group 5 308 GTB Turbo was that it showed the potential of the 308 block to produce massive power outputs and perhaps have a future in competition. To some extent, this potential was confirmed by the Lancia LC2. But at least the Jolly Club project had resulted in a turbocharged Ferrari V8 being used in a car named Ferrari, even if it wasn't a factory effort.

Now, let's return to 1985 and the events which had to result in a Ferrari Indycar.

Trueman and his driver Bobby Rahal visited Ferrari in the fall of 1985. Rahal demonstrated a (red) March 85C at the Fiorano test track for 40 laps. Alboreto also tried out the 85C. The first test led to an order for special Goodyear tyres better suited to the Fiorano track. Rahal was impressed with the kindness and respect he received at Ferrari. It made him realise that this was a serious thing.

Michele Alboreto test driving the March 85C.

The March was further tested during the winter. This resulted in Ferrari actually giving the order to design a suitable engine. This engine eventually got the type registration 034. But instead of only building an engine Ferrari decided to go for an entire car. His newly recruited designer Gustav Brunner got the task to design a CART chassis. It would eventually become known as project 637. It is said that Brunner only needed a few days to set the outlines for this new car.

Ferrari had given orders to start this top secret project for real. Harvey Postlethwaithe was to be the project leader with Antonio Bellentani, the famous bald F1 mechanic, Colombini and Gualmini joining in. Marchetti would be responsible for the engine and gearbox. A smart team doing its own thing inside the house of Maranello. Many inside Ferrari wondered what those guys were up to. The 034 engine was remarkable for having its exhausts within the V with the inlet manifolds positioned outside the engine, in the sidepods, with updraft charge flow into the cylinders, a configuration already seen on the turbocharged Ferrari F1 cars built between 1980 and 1984.

During the turbo era in F1, Ferrari was the only constructor of a Vee-type engine which had the exhaust within the V of the engine and the inlet manifolds on the outside. The wide Vee angle of the Ferrari V6 (120 degrees) permitted this layout. This is a 126C3, pictured in the paddock at Zandvoort in August 1983. (photo HG)

The turbocharger itself was in the usual location, for a CART racer, behind the engine above the spacer and gearbox. Otherwise the inlet and exhaust system was totally different from contemporary design trends in Indycar racing, though not entirely unknown. The Quadcam turbo Ford/Foyt used between 1968 and 1978 also had the exhausts within the V. But the Ford/Foyt Quadcam had downdraft inlet manifolds located between the two camshafts.

The first V8 engines used at Indianapolis with exhausts within the Vee were the Ford Fairlane derivatives. The quad-cam 32-valve 4.2-litre normally aspirated version that debuted in 1964 is in the background. Turbocharging it with a single turbo created its own logistical nightmare if it came to an even distribution of the boost to the cylinders. Introduced in 1968, as a 2.8-litre. Since 1969, due to rule changes, despite its colossal size, this heavyweight had the same swept volume as the Ferrari 034 engine: 2.65 litres... (photo HG)

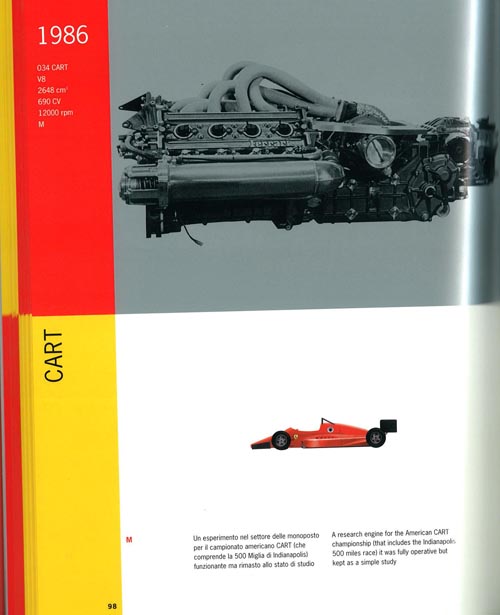

Pictures of the Ferrari 034 engine in or out of the car have been difficult to find. This page contains a small picture of the Ferrari 637, showing off its engine installation within the chassis.

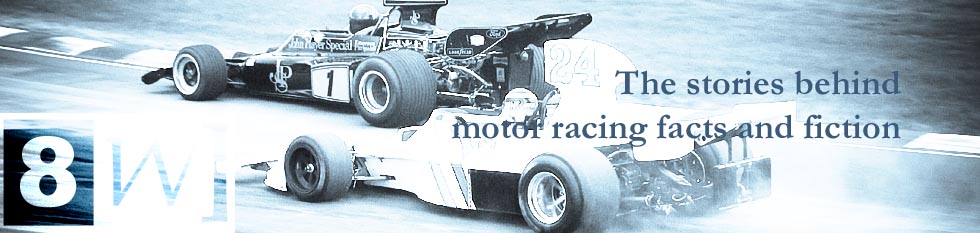

The complete drivetrain of the Ferrari 637 has been pictured in the book Ferrari Tutti I Motori. This is the page in question. (photo Arjan de Roos)

There were a number of differences between the original 2.6-litre 268/282C engine used in the Group C Lancia and the 034 CART engine as can be seen in the following overview.

| Ferrari 268 (Lancia LC2) | Ferrari 034 (CART) | |

| Year of build | 1983 | 1986 |

| Bore x stroke (mm) | 80 x 64.5 | 86 x 57 |

| Capacity | 2593.7cc | 2648.8cc |

| Compression ratio | 7.0 | 11.5 |

| Fuel | gasoline | methanol |

| Power @ rpm | 620bhp @ 8200rpm | 690bhp @ 12,000rpm |

| (also published) | (710bhp @ 11,500rpm) | |

| Turbo | two KKKs with intercooler | 1, no intercooler |

| Maximum pressure | 1.3-1.45 bar | 48 Inch Hg = 1.6 bar |

Even though a collaboration between Ferrari and TrueSports was envisaged, TrueSports had ordered new Marches (86C) for 1986. This led to speculations that Ferrari would only enter the final races of 1986 and do a full season in 1987. Jim Trueman’s death, eleven days after the Indy 500 was won by his car and driver Bobby Rahal (!), eventually fuelled doubts over the link-up.

With a possible cooperation with Ferrari coming up, Truesports Racing most definitely must have impressed their future partners during 1986 with winning The Big One that year. In May 1988, the winning car was on display at the IMS Museum. With hindsight, this was truly one of the most unlikely 86Cs of them all to win the race. Before being qualified, it began the month as the backup chassis, maybe because of its chassis number? That was 86C-13... (photo HG)

In the summer of 1986 Ferrari had a CART racer ready for testing. On Sunday, July 20, Franco Gozzi (Ferrari's secretary) posed with the car and its team. They fired the car up and made some 'secret' pictures that were leaked to the press, so all who needed to know could see the real thing.

Brunner's influence on its design was obvious. The front end of the car looked very similar to one of his last F1 designs, the 1985 RAM-Hart. In an interview with Brunner in Motorsport Aktuell he stated that he found the nose of the Williams FW09 innovative in the way that the airflow was better distributed along the sides of the car, and not just kicking it up. In the RAM 03 as well as the 637 we can see some resemblance to the FW09. There was talk about the car being fielded by a factory-supported team. Bobby Rahal and Andrea de Cesaris were named as potential drivers, especially Rahal after he declined a Lola Haas offer to race F1. Sponsors seemed to be in place: Marlboro (quite prominently in sketches in Autosprint), Goodyear, IVI (a paint company jointly owned by PPG and Fiat) and also Fiat itself. A major sporting challenge was on the cards with rumours that Porsche, Lotus, Alfa Romeo and Honda would enter CART as well. First tests with Alboreto had been planned at Fiorano and later at Nardo.

As history proved, of all the rumoured companies to become involved with CART, most of them were indeed true or came close. Lotus built a prototype (the all-carbon 96T) but that car was banned and never raced. Porsche entered from late 1987 on. It would take a while before Honda appeared in CART but from 1994 on they became engine suppliers. Alfa showed up from mid-1989 on.

On September 24, 1986 Ferrari held his annual press conference. He had two big announcements. Gerhard Berger would join the F1 team and John Barnard was to be appointed technical director from November 1st. Brunner and Postlethwaite were mentioned as his assistants. Ferrari also stated the Indycar was well underway and even showed the engine to the press for the first time: a V8 with exhausts exiting upwards out of the V looping to the IHI turbo and with a CART pop-off valve. Mounted to its gearbox the engine was for real and surprised all those who attended.

In the middle of November 1986 Ferrari presented his new F1 team. It was clear that Ferrari was pulling out all the stops to get on top in F1 again. For Barnard he made several sacrifices unheard before, and not just salary-wise, since Barnard would be operating from the UK. Ferrari also regarded Barnard as a man to oversee all racing activities. In this press conference Barnard stated that he was to revise the 1987 F1 car first, then design a new 1988 car and put the Indycar project on hold until Ferrari was on top again in F1. In fact from day one Barnard pressed Ferrari to abandon the Indy project claiming that F1 needed all its focus, and that the 637 Indy would only be a distraction.

Around the same time Steve Horne, now the leading man of TrueSports, visited Ferrari again. He got to see the car as well as the engine (on the dyno), but also Horne learned that Ferrari would concentrate on F1 first now, despite the fact that Truesports, in Rahal, had the CART champion and Indy winner.

Then everything changed in Formula 1. All of a sudden the rules that promoted turbocharged engines were reversed and the FIA announced that from 1989 on, Formula 1 would be for 3.5-litre normally aspirated engines only. The maximum number of cylinders was to be 8. This didn't go down well at all with Enzo Ferrari who favoured his beloved traditional twelves. The FIA, however, was unwilling to give in to his requests. But the FIA had a problem as well.

CART's ever-increasing popularity wasn't very well appreciated by the men in charge of Formula 1 as it rivalled their championship too much, particularly on the American continent. And although Ferrari wasn't going through a particularly successful period, it was still the most renowned, popular and best known team in Formula 1. A Ferrari switch to CART, however, would be very beneficial to CART while working against Formula 1's popularity yet again.

The story goes that somewhere in the second half of 1986 FIA and other F1 representatives came to Maranello to speak with Enzo Ferrari about the future of F1 and tried to persuade him to remain in F1. It is said that Enzo told them he was willing to do so but if V12s would be disallowed he couldn't guarantee his company not pursuing other options. Hardly had Enzo spoken these words or everyone in the room heard an engine being started, which could be identified as a turbocharged V8 of about 3 litres, with Ferrari pointing out to the people in the room what they were hearing. The attendants supposedly all of a sudden realized that Ferrari was indeed in an advanced state with its Indy project. At that moment, the deal was struck that V12 engines would be allowed in F1, under the condition that Ferrari wouldn't further pursue its Indycar plans. The project 637 came to an instant standstill as a result.

The details of this story are the stuff legends are built upon. There is little reason to discard the story as an impossibility. But is it entirely accurate?

In March 1987, a new Concorde Agreement was signed in Maranello. Both Ecclestone as Balestre were present and Balestre made a speech in which he called Enzo Ferrari the pope of F1. Peace was signed and Ferrari was presented a plaque with an inscription to honour his 70 years in racing and 40 years as the head of his company.

The story about Enzo Ferrari giving up the Indycar project in exchange for being permitted to build V12 F1 engines is the one that is told most often. One could of course also wonder if the FIA, weary about Ferrari's CART plans, set up the situation, coming up with the 8-cylinder limit for the new 3.5-litre atmos, knowing full well that the idea wouldn't resonate with Ferrari. The rule proposal gave them a negotiation tool in case Ferrari should start pushing for a 12-cylinder limit. Who held the strongest cards in this poker game?

Sacrificing the Indycar in exchange for V12 F1 engines isn't the only story explaining why the Project 637 Indycar was parked. There is also talk of the influence of newly hired John Barnard who wanted the 637 cancelled in order to keep the focus on the F1 project was a very important factor behind the cancellation of the CART racer.

For what it's worth, an article published in a Dutch newspaper early 1987 previewing the upcoming CART season mentioned that Ferrari was expected to enter the series late 1987, on October 11 at Laguna Seca. Bobby Rahal was listed as having done some testing for Ferrari. The article also mentioned that the Ilmor Chevrolet engine would be available to anyone for the following (1988) season. (Now make up your mind about the reliability level of this article.)

In an article published in Dutch magazine RTL GP in late 2009, author Mark Koense told that the explanation most given to why the Indycar was built (as a means to put FIA under pressure to allow the continuation of V12 F1 engines) was not the main reason. According to Koense, Ferrari's plans to enter CART were much more serious and sincere: much more actual planning was done than many realized.

The financial investments for it alone had been quite tremendous. In a time when Formula One was becoming an ever more expensive effort in which by now millions of dollars were spent, designing an entirely new engine and chassis was quite an effort which also had taken a substantial amount of money that could also have been directed elsewhere. Remember that 1986 was by far Ferrari's worst year in F1 since the nightmarish 1980 season. 1986 wasn't as bad as 1980 but it was the first year (and, with hindsight, the only year) in which turbocharged Ferrari F1 cars failed to win at least one Grand Prix. Barnard's insistence on preventing distraction through other projects, instead focusing entirely on F1 to become successful again, wasn't without reason.

According to Koense, the men at Ferrari who were in charge understood this line of thinking and, more importantly, began to see that it would be near impossible to generate the sponsorship necessary to be competitive in two important single-seater formulae at the same time. Even with the sponsors Ferrari had (and according to stories there was substantial funding for the Indycar programme) doing CART and F1 was simply too much. The decision to cancel the Indycar project was thus taken with some sadness but with well-supported reasoning. It was a decision that assured that no more money was lost on a project which already had cost Ferrari a lot of money. According to Koense's theory it had cost too much money for something solely intended to put FIA under pressure.

One of the parties involved with the project was Truesports Racing, which fielded driver Bobby Rahal. In a conversation I had with Bobby about the Ferrari Indycar project he told me that based on what he knew about the entire deal that Ferrari had been deadpan serious with the plans, having done so much, involving so many other parties and people that for him it was difficult to believe that it was all done just to have something to sacrifice in negotiations with FISA.

Based on what Rahal told me I began to believe that Koense's theory is correct. The amount of money spent on designing and building an entire car and have it ready to run and start testing must be substantial. Who would spend so much money 'only' to blackmail the FIA? If it was only for that purpose, Ferrari could have done it cheaper and still make it look like a serious effort.

Even though it was going against their principles to use a chassis built by others, Ferrari could have started with developing an engine, accepting that for the time being their partners would start off by using an alternative, familiar chassis in order to have a valid reference point with which to compare their progress. Such an approach would have been sensible as well. When the Ilmor 265A V8 (the Indy Chevy V8) made its debut in Indycar racing in 1986 it was built into a bespoke chassis: the Penske PC15, Penske that year having exclusive use of the engine. The wisdom of this decision may be questioned since Penske was in a period of time in which they had 'lost it' when it came down to building competitive chassis. The decline had started with the 1983 PC11, which during the season was replaced with the PC10B, an updated version of the previous year's (successful) car. The 1984 PC12 was deemed a failure and Penske saved its season by buying March 84Cs in time. Team Penske's prime contenders during 1985 were March-Cosworth 85Cs. In 1986, Penske relied on Marches again (the new 86C) in addition to the Ilmor-powered PC15 that eventually was backed up by March chassis to continue the development of the brand new engine. Even as late as 1987 Penske had to park its self-built PC16s and give the 86Cs a second year of duty, this time with Ilmor power. Later on it transpired that a number of the development issues with the Ilmor 265A were related to the fact that the engineers simply had no reference data for their engine in comparison with a proven chassis. Also, Alan Jenkins, the designer of the PC15 and PC16, stated that because of the Ilmor's early unreliability he had difficulties developing his designs into competitive cars. Now, knowing all this, make up your own mind about the wisdom of developing a brand new engine with the help of a brand new, bespoke chassis and vice versa while ignoring all available proven alternatives.

It most likely would have taken Ferrari a mammoth effort to swallow its pride and let another manufacturer provide a chassis for their lovely new Indy V8, even if only for the test phase of the engine. But as the story about the Ilmor Chevy and Penske proves, it made sense to test a brand new engine in a chassis with known capabilities and swallow your pride for the sake of progress. And for the time being, while concentrating on the engine, Ferrari could have saved themselves the (financial) investment necessary for designing and developing their own chassis. Using the Ilmor situation as a guide, an announcement that an engine was built and tested in a chassis that was available would likely have been more than enough for anyone to take the Ferrari Indy plans very seriously indeed.

Having said that, if Ferrari wanted to show that its Indy/CART plans were nothing less than bloody serious, the only thing left to do in addition to developing a suitable engine was creating an entire car around it, which was exactly the approach Ferrari was known for.

By this time, the plan was in such an advanced state that it is difficult to accept that it was all undertaken to simply persuade the FIA to allow V12 engines in F1. Also consider the fact that the plan would have given false hope to US people and companies who could have been a part of the project. Would Ferrari really have 'abused' those to have the FIA give in to their F1 wishes, especially given the fact that such an abuse would have had dire consequences for the partners involved? The Truesports team, with Bobby Rahal driving for them, was a competitive team, winning Indy in 1986 and the CART titles in both 1986 and 1987. However, for a very long time Truesports was denied the use of the Chevy/A engine, and from 1988 on the team lost some of its edge because of that. Instead, the team had to resort to using Judd engines and it was only in 1992, in what was eventually the final year for the team, that was able to obtain a Chevy/A lease contract. It has been suggested that Ilmor didn't want to supply Truesports with their engines because of the connections with Ferrari. (See Footnote 2 for more on Truesports' achievements.)

It can't be said that everyone involved with the Ferrari project could have expected, let alone known in advance they would somehow be punished for it, at once or in the (near) future. Nevertheless, I find it difficult to believe that Ferrari teased a number of people and organisations into participating in a Ferrari project in the full knowledge they were misleading them.

However, it might be entirely possible if not very likely that it was made easier for Ferrari to cancel the project once the V12s were allowed back into the new-style atmo F1 after all, and then use it as an excuse for why the car was built in the first place. The story made Ferrari look determined and willing to go beyond the call of duty to maintain F1's engine variety, something that would appeal to a large number of fans worldwide. These fans owed it to Ferrari that there wouldn't be a return to something similar to the Cosworth DFV era.

When looking at all aspects, building the entire 637 with its brand new bespoke engine, or if you prefer, the 034 engine with an entire car designed around it, in the knowledge it would never run in anger, reminds me of the infamous moon hoax, in which billions were spent to have people believe in a lie. It's the story of NASA knowing that they would never be able to make it to the moon, so instead they choose to set up a programme to fool the American people that they in fact had been to the moon. This would have meant spending an incredible amount of money building Cape Canaveral with the VAB (the building where the supposed moon rockets were built) and developing and launching the 110-metre Saturn V rockets, while also not using the golden opportunity to end all cheating after a 'successful failure' - Apollo 13's shipwreck in space - that first had to be set up as well, of course! Instead of using this perfectly planned and executed 'moon mission' with its dramatic ending almost ending in tragedy to gracefully end all the misleading the 'Apollo show' went on. Four more Saturn V boosters were built and launched to (supposedly) put, among other things, three cars on the moon…

So why not save the money and use it on the Space Shuttle programme instead? That was heavily compromised in design because of its shortage of finance. The Shuttle could have done very well with the money saved by cancelling these supposedly fake moon flights of Apollo 14 to 17.

Would the United States really have spent billions of dollars supporting a hoax, with the risk of being exposed as cheats if their enemy had ever found out? If Leonid Breznev knew he was made to believe the Russians lost the moon race because of a hoax, would he have had the Americans get away with it?

A postcard bought on the location where according to some people the biggest and most costly hoax in history took place. This is the launch of Apollo 11 on July 16, 1969. Nine of these dangerous spectacles, all simply to support a lie? (image copyright NASA)

I admit a fake moon landing is on entirely different level and scale than a fake Indycar programme. But there is one similarity at least. If the amount of money spent on a project reaches heights that are off the scale - which lots of the ensuing hardware still visible today - it is time to accept that it was all for real.

In 2009, writer George Phillips mentioned the 637 in his article on Ferrari's possible participation at Indy. At one point in his article, Phillips is quoting Truesports boss Steve Horne who to this day insists that “Ferrari had every intention to run the car in CART, yet changed their mind at the last minute.”

Evaluating the potential of Motori Otto Vu Tipo 034 and Monoposto Tipo 637

Do Ferrari fans have to regret that Project 637 was parked or must they be grateful not having to endure seeing their beloved team fail as it did in F1?

It's very difficult to evaluate the 637's competitive chances. The engine is said to have inspired the Alfa Romeo Indycar project that started late 1988 and ended after the 1991 CART season. Do Alfa's initial experiences represent what Ferrari could have expected to happen? Alfa was up against the Ilmor 265A which gained the upper hand during 1987 and, from 1988 on, was the engine to have. But like the Ferrari 034 engine, the Ilmor was still new in 1986 and had yet to be sorted out. Because of its stunning success between 1988 and 1992 the Ilmor's painful teething program during 1985, 1986 and, to a lesser extent, 1987 is largely forgotten. So what if the Ferrari 034 engine had been right in the ballpark from the very beginning?

But was it? We know that the 034 Ferrari engine supposedly inspired the 1989 Alfa Indy V8. During the Alfa engine's first tests it proved to be some 100hp down on the Cosworth DFX, which is turn was known to be down on power against the Ilmor 265A. That is, unless Alfa managed to ruin something that had been right until the moment they took it over. Such appears to be very unlikely. Nevertheless, and I realize this might read as an insult to Alfa Corse, but given Alfa's record in the years before, I dare not exclude the possibility of Alfa having messed up for more than 99.9%...

Chassis-wise, the 637 remains much of an enigma. There is simply nothing to say about its qualities since most reports say that the car has driven one single shakedown lap at Fiorano. Chassis constructors other than off-the-shelf suppliers March and Lola had a tough time in the mid-eighties. Ligier had tried Indycars in 1984 but pulled out after a few races since their car was hopeless. Doug Shierson had done the same with his DSR chassis that same year. Kraco Racing had built a car of their own for 1986 but after much persuasion by March it never raced. How much persuasion? How about getting Adrian Newey, the 86C's primary designer, getting transferred from Truesports to Kraco as the March representative/engineer? At the same time Ferrari worked on their Indycar, Porsche was working on their own Indycar as well, including the chassis, the Typ 2708. That car did debut in the last two races of the 1987 CART season and was considered a disaster. Penske had been forced to pull their PC16 during 1987, swapping them for the March 86Cs they had already used in 1986. Dan Gurney's Eagle company was still running their own cars in 1985 and 1986 but was losing grip on the situation as well. He quit at the end of 1986. These weren't encouraging signs for anyone eschewing March or Lola cars. However, that doesn't imply that Ferrari was in the same corner and that the 637 was a dog of a car. It could well be the exception to the rule but there is simply no decisive evidence for either side of the argument.

Then again, designer Gustav Brunner's experience with Indycars was limited. How much influence did this have on the eventual car? Was experience of importance? Based on the Penske and Eagle troubles, experienced designers were no guarantee to get a decent car. But Ferrari literature published at the time the Indy plan was announced said that Brunner's lack of actual experience wasn't that much of a handicap since Indycars were less sophisticated and several European constructors were doing very well. Makes you wonder what the Porsche designers and engineers on Porsche's 2708 Indycar chassis have to say about that comment.

Perhaps it is also interesting to point out that in 1980 and 1981 the Longhorn team built an Indycar based on the highly successful Williams FW07 F1 car. The Longhorn didn't live up to the expectation one might have had given its pedigree. The Williams FW07 was a hallmark car in F1 history. March, on the other hand, had built mediocre F1 cars that hadn't been a match for the later FW07 versions. The Indycars derived from these F1 cars, however, were competitive and eventually dominant, not in the least because of their sheer number in the field. So it's very difficult to gauge the importance of recent CART experience and that of being involved with an F1 top contender. From 1983 on it became impossible for F1 designs to be an inspiration to Indycars since ground effect was banned in F1 from 1983 while Indycars retained the principle.

There's simply not enough hard data available to judge if Project 637 could have made Ferrari proud, with only some vague signs suggesting to me that the entire car wouldn't have been very successful, since Ferrari would have had a lot to learn with the car, both engine and chassis. We will simply never know how its real chances.

One of the few clues of how good the 637 may have been can be found in the aforementioned George Phillips article. Phillips stated the 637 tested against a March 85C, with the 637 coming out favourably, although he didn't mention the source behind this fact. However, Phillips does say that according to Steve Horne “the 637 had impressive windtunnel numbers and was very innovative.”

Of course, this doesn't promise anything yet. There is no doubt that the Brabham team had seen some impressive windtunnel figures for their F1 car of the same year (1986), the lowline BT55 with its laydown engine. Yet that car was a total disaster to drive.

Also, the cynics who know a bit about CART in the eighties will instantly point out that it doesn't say very much if the 637 compared favourably to a 85C in the summer of 1986. The car to beat in 1986 was the March 86C, which was steps ahead of the 85C and (at least) at Indianapolis much better than the single 85C that managed to qualify for the race. In fact, both March and Lola's 1986 cars were faster than 85Cs. At first sight already the 86C appears less bulky, with a smaller frontal area than the 85C. To the 637's credit it looked to have much more in common with the 86C than the 85C.

If Indianapolis was indeed Ferrari's major aim it is worth to remember that its first opportunity was to be the 1987 Indy 500. Although the Lola T87/00 was the best chassis at Indy that year, the 86Cs were at least as good if not actually better than the 87C. So good in fact that as late as 1988 some 86Cs still managed to qualify at Indy, with some smaller teams preferring the 86C over the 87C! The ultimate proof of how good the 86C was? As late as 1989 a 86C qualified for the 500 using a regular Cosworth DFX!

This particular 86C was entered by AJ Foyt who also fielded an 86C powered by a turbocharged Chevy V6 stockblock. This engine held at least 100 to 150hp over a quadcam V8 engine but with a near ridiculous level of unreliability. This very same 86C-Chevy V6 was driven in free practice for the 1990 Indy 500, on a single day and for a couple of laps. It appears there was never any intention to try to qualify the car. Due to rule changes the underfloor of this 86C had to be modified, with loss of downforce as a result. Nevertheless, it appears in the lists of the IMS Timing & Scoring Department as having been faster than the brand new Alfa Romeo V8-powered March 90CAs! Ouch.

So, of how much value was it for the 637 to be faster than a 85C in the summer of 1986? The question of it being fast enough take on the 86C was of much more importance. And assuming that the car was to see more action in 1987, how well would it have done against the new 1987 contenders built by both Lola and March? Or would 637 have ended up as the test hack that never raced, to be succeeded by a new design that benefited from the experience gained with the 637?

Still, there is one more tantalizing thought. Leo Mehl's choice of Truesports as a partner proved to be more than right.

Regarding the speculation about a late 1986 season debut for a Ferrari 637 run by Truesports, there is a good point that would have made that very unlikely: Truesports and Bobby Rahal were still very much involved in the title battle. Early September, in the 12th race of the season at Montreal, Rahal took the lead in the championship battle but Michael Andretti and Danny Sullivan followed within 6 points. Sullivan was unable to follow the other two in a title chase that went down to the wire, with Rahal in a three-point advantage over Michael Andretti. Just ahead of half-distance, Andretti had to retire and Rahal's title was secure. The 8th place he scored merely extended the gap.

It makes you wonder how prestigious debuting the CART Ferrari may have been for Truesports. Prestigious enough to take the gamble of relying on an largely unknown quantity with the risk of losing the CART title? With Indianapolis already won that year, the season was a success but would Truesports have dared losing out on the double because of debuting the Ferrari?

Somehow, even in the most ideal situation, and with the 637 being available and ready for a late-1986 debut, it looks unlikely that Rahal would have ended up in the car in those final races of the season, with the CART title at stake. We can only speculate how the Ferrari would have ended up on the starting grid, provided it would have qualified. In the case of it being too slow, unless it wasn't ridiculously off the pace, a 'promotors option' would likely have ensured the Ferrari to at least start the race. The identity of the driver, however, is anyone's guess.

To the surprise of many, Truesports went with Lola chassis in 1987, instead of sticking with March. The gamble paid off since Bobby successfully defended his CART title. At Indianapolis his glory was restricted to practice and qualifying, with the second fastest time of all starters, but Rahal was forced into an early retirement. Only Mario Andretti in his Ilmor-Chevy-powered Lola was faster in practice. In other words: if you gave them competitive hardware to work with, Bobby Rahal and Truesports brought the results home. Which makes you wonder what would have happened if they had indeed got their hands on the Ferrari hardware. What if the entire project had been good? Or what if the engine had been good enough and fitted into the devastatingly good Lola chassis? Or, just imagine that the 637 as a whole was a competitive package, suitable for CART combat and fielded by Truesports that season's end?

We will never know. But it's justified to conclude that Ferrari had found a good partner in Truesports if they had wished to continue the Indy project.

Back to what did happen. So was it John Barnard who had been behind the cancellation of the Indy programme and managed to convince the Ferrari management to focus on F1? Then the truth must be said: the decision was justified and to some extent vindicated. Because after the poor results of the last quarter of 1985, which had cost Ferrari a possible championship, and all of 1986, the Ferrari F1 team endured a lousy start to 1987 in which it appeared to still have lost all direction. Winning titles against the might of Williams-Honda and McLaren-TAG (Porsche) was impossible but during the 1987 season Ferrari finally began to get their act together again. At the very end of the season the team broke their two-year drought of GP victories by winning the final two races, one of those taking place in World Championship engine partner Honda's home country of Japan. It appeared as if Ferrari had at last found its feet again, ending the season with high hopes for 1988. Sacrificing the 034-powered 637 appears to be have been the right thing to do.

Of all known Ferrari Indy plans that never happened this mid-eighties plan is the one that came closest. Unlike a number of earlier plans the hardware required was actually built, but the 637 is remarkable in another aspect as well. It was Ferrari's last Indycar plan while the Old Man was still alive, and Ferrari's last Indycar plan ever. From 1987 on, Indy forever disappeared from the Ferrari agenda, made even easier when the IRL was founded in 1996 and took over the creation of Indy regulations. Engine-wise in particular, IRL made rules that were impossible for Ferrari to comply with. Regarding chassis, there was an escape clause since the Italian Dallara company became an IRL chassis supplier. Dallara had been involved in several projects by the FIAT group, such as the Lancia LC2 Group C chassis. If IRL had made it possible and if Ferrari had engine that were eligible for the IRL, Dallara most definitely would have been the most suitable partner. But it never happened.

Project 637's fate after the premature end to its career was rather interesting. Once Alfa Romeo had decided in late 1988 to take up the Indy challenge the 637 was made available to Alfa in order to provide an insight into Indycar/CART technology that was fairly recent. It has often been mentioned that the Alfa Indy engine was simply a reworked version of the Ferrari Tipo 034 engine. However, this was not the case, The Ferrari V8 provided the inspiration but was a different beast.

In early 1989, Doug Nye published an article in Fast Lane magazine about his visit to the Alfa Corse workshop where he saw the 1989 Alfa V8 Indycar engine. He also spotted a white-painted monocoque carrying an Alfa Romeo decal on the nose. He nevertheless identified the car as being the 637. The car remained missing for a while but was rediscovered in 1992, after Alfa's withdrawal from the CART World Series. Thanks to Giorgio Pianta (amongst others) the car was built up again and then went to the Ferrari museum.

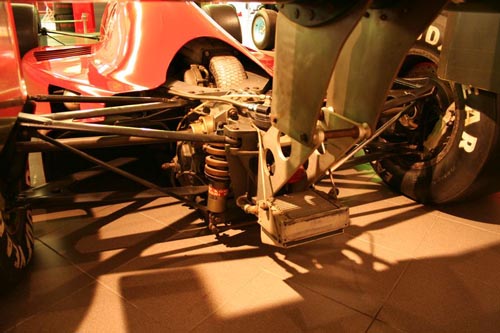

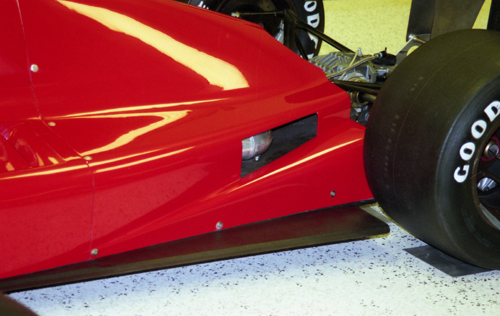

The Ferrari 637's vertical profile reminds us a lot of the March 87Cs in use at Indianapolis in 1988. (photos by Arjan de Roos)

The car has been exhibited there but also went on tour since it has been seen at other locations. The car eventually made the journey to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway after all! This happened somewhere near the end of 1993 or the beginning of 1994, only to appear in the IMS Museum. In an article about the car the IMS stated that it on loan for a while during 1994. I saw the car in January 1994 but when I returned to Indy in May 1994 it was no longer there.

A few years late, the Ferrari 637 finally made it to the hallowed ground of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. In January 1994 I was at Indy doing research on location for an entirely different project. To my utter surprise I stumbled upon the 637 exhibited in the IMS Museum. It was unusual to see an Indycar there that never raced at the Speedway but the badge on this car made all the difference. Some interesting observations: the left sidepod had an opening at the short side ahead of the rear wheel but the right sidepod didn't have one. Also, the engine cover above the turbocharger appears to be very low, suggesting the turbo itself is situated very low within the chassis, perhaps even lower than in the 1986 Lola and March, foreshadowing the trend of building turbos within spacers between the gearbox and engine? (photos HG)

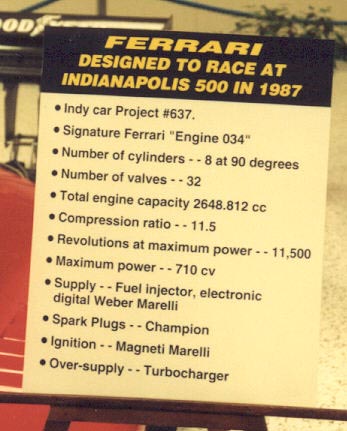

This is what the information board said about the car. The museum didn't put up one of their own info boards as it normally does. (photo HG)

Footnote 1: mid-eighties Ferrari cars acting as TV stars

Even more popularity for Ferrari production cars, both in America and worldwide, came from appearing in popular TV series such as Magnum PI (Magnum ever so often driving a red Ferrari 308 GTS, the Targa/Spyder version of the 308 GTB) and Miami Vice (stars Tubbs and Crockett using a black Daytona Spyder as their form of private transportation). Ironically, the Miami Vice Daytona wasn't the real deal but a kit car based on a Corvette. This didn't go down too well with Enzo and in 1986 he saw to it that the 'Daytona' was phased out at the expense of two white Testarossas supplied to the producers in order to provide Crockett with a new set of wheels and keep a Ferrari presence in the show.

No doubt that these TV appearances had an effect on the popularity of production Ferraris.

Footnote 2: The fate of intended Ferrari partner Truesports

While Truesports was denied the opportunity to field Ferrari's Indycar, the team continued racing and somehow chose to pursue options to succeed by using a different car than the majority of the opposition.

After winning both the CART title and Indy in 1986 with a March-Cosworth 86C the team surprised many with changing to Lola chassis for the following season. At Indy, Bobby Rahal was second fastest in qualifying and among the fastest behind the man of the year, Mario Andretti in an IImor-Chevy-powered Lola. Regrettably for Rahal, he suffered from a very unusual jinx: finishing high and well (including a win) in even years, finishing way down the field (and on one occasion failing to qualify!) in odd years. (We could have mentioned this jinx in the 1956 part where we dealt with some long-lasting Indy jinxes...)

But despite Indy being a write-off (1987 was an odd year, you see), using the best chassis of the year combined with Cosworth DFX reliability earned him a second CART championship.

For whatever reasons Truesports was denied the use of Ilmor engines, so for 1988 Truesports took a gamble on the Judd V8 powerplant for their Lolas. Since Rahal was still with the team and it being an even year, fifth place at Indy was a decent result given the fact that the Ilmor-Chevy was by now reliable and dominant to near unbeatable, especially when fitted in Penske's PC17.

Truesports Lola-Judd. The 1988 Truesports entry, driven at speed. (photo HG)

Rahal did manage to win one of the Blue Ribbon events of the 1988 season. The Pocono 500 was perhaps the least glamorous of the three 500 milers but still a classic event and of “hallowed distance”. It was however the only victory of the season. The Judd was underpowered against its main opponents yet very fuel efficient which on several occasions yielded decent results after all.

Rahal left the team in 1989, with Scott Pruett taking over the Truesports drive, driving new Lolas with Judd engines. At Indy he finished 10th, 10 laps down on the winner.

1989 Truesports Lola-Judd. The 1989 Truesports car looked almost identical in shape to the 1988 car. Differences between the '87, '88 and '89 Lolas require a good look to find them anyway. (photo HG)

For 1991 Truesports intended to build their own chassis, which had its ramifications in the year before since in 1990 new rules had been implemented regarding the maximum height of the sidepod underfloors, reducing this from 10 to 8 inches. For older cars that were to be used another season that meant that inserts had to be installed in the floors to bring them up to the required height. Newly designed cars, however, started a trend in which the overall height of the sidepod was lowered as well, in order to reduce frontal area. At Indianapolis that year, according to the 1990 Hungness yearbook, there were four separate classes of cars.

- First: The brand new 1990 cars with Ilmors

- Second: The brand new cars with anything else but Ilmors

- Third: Older cars with Ilmors, and finally

- Fourth: What older cars were left.

From personal experience this was indeed a correct observation, although the ranking of the second and third class is debatable. These might also have been the other way around.

Truesports hadn't invested in new 1990-built chassis, instead opting to give their 1989 car another year of duty, thereby saving money for their new homemade car. They did do windtunnel tests to develop an undertray according to the new rules. It worked well. Regrettably for the team, Scott Pruett had a massive accident early on in the season and was sidelined for the rest of the season, so Raul Boesel took over the ride. Geoff Brabham drove a second Truesports entry that year, in another Lola-Judd. The Truesports-modified '89 Lolas were among of the fastest and best handling older cars. In fact, it was such a good handling car that the AMAX team of Tony Bettenhausen, which also ran a '89 Lola, invested some of their sponsorship money in buying a Truesports-designed and built undertray for their car. Truesports success in the race was compromised by running the underpowered Judd against the Ilmor. Moreover, Boesel retired after 60 laps with an engine problem. Geoff Brabham finished 19th and running but 39 laps behind.

1990 Truesports Lola-Judd. This car was in fact the bridge between customer Lola chassis and the self-designed and self-built car. Modifications compared to the standard T89/00 were primarily done to the underbody of the car, so not visible. (photo HG)

Truesports did indeed debut their self-built car with all-carbon monocoque in 1991, the Truesports 91C. At Indy the team fielded two cars but the race results weren't all that impressive. Lack of (Ilmor) power was a big problem. Still, the significance of these cars must not be underestimated: they were the only two cars in the field with monocoques built in the US. In the 1956 chapter we already mentioned how Indy seems to be ruled by various jinxes, one of those being the once-a-dozen jinx from which Lola suffered. So with hindsight, Truesports had enhanced its chances by at least avoiding the use of Lola cars. A more powerful engine might have made a difference, though. Regrettably, of all the marques other than Lola racing at Indy between 1991 and 1996, Truesports was the only one never to win at least a single 500 and, like Lola, remained winless in these years.

Impressions of the 1991 Indycar that was the most American of them all and dared to show that off with a Stars and Stripes on the nosecone. Don't you think that the tip of the nosecone is looking vaguely familiar? I have never been able to find out what the fin beneath the gearbox was for. (photos HG)

And this is how the car looked in high-downforce trim, here seen on the Milwaukee oval. (photos HG)

Finally in 1992, the Truesports team was able to obtain a supply Ilmor engines. Their new 1992 challenger was fitted with such an engine. Pruett was by now the lone Truesports driver and regrettably an early retirement after 30 laps.

The Truesports 92C looked different from its opponents but was rated as a car with potential. Regrettably at Indy, the result wasn't encouraging. (photo copyright John Darlington, used with permission)

During the season the results were few and far between despite the promise the car definitely possessed. But it all came too late.

Truesports was disbanded in 1993 and all remaining hardware was sold to Rahal-Hogan Racing, partly owned by Bobby Rahal. The '92-type Truesports was renamed R/H 001 and fitted with the new Ilmor/C engine. Rahal finished second at Long Beach mid-April but a month later, to the sheer amazement of almost anyone, the car was simply too slow, defending CART champion Bobby Rahal failing to qualify for the Indy 500! That was the end for the entire Truesports adventure since Rahal hurridly switched to Lola chassis for the remainder of the season. After Indy, Mike Groff did four more races in the car but eventually the project was canned. A sad end to the story of a name that earned respect in Indycar racing.

One year later, looking a bit more conventional, as its opponents, the last ever contribution to Indy related to Truesports was a failure to qualify by former Truesports driver Bobby Rahal in a car formerly known as a Truesports... (photo HG)

Truesports was a team that dared to be different and look for other options in order to be successful. Its technical staff was also capable. Indeed, they should have been capable Ferrari partners in CART. Regrettably for the team, its alliance with Ferrari that eventually resulted in nothing played a part in the decline of the team as a competitive outfit and its demise. Given the state of CART at that time, it was a pity that such a competitive team in the late eighties was no longer a factor in the early nineties when CART was seen as world-class series with ever-increasing worldwide appeal: exactly that what Bernie Ecclestone and the FIA had tried to prevent a few years earlier when it looked as if Ferrari could become a participant in the series...

Then again, if you remember that supposedly the Ferrari Indycar assets were taken over by Alfa Romeo to appear in CART in 1989, the inevitable question arises: after Ferrari's positive experience with Truesports, why didn't Alfa team up with it?

But that's an entirely different story.