The 1970s: trial and error in Formula One design

Author

- Willem Visser

Date

- October 2, 2013

Related articles

- Swoosh and screech! The rise and fall of turbines and CVTs in motor racing, by Mattijs Diepraam

- Introduction: Sixties lateral thinking

- Part 1, turbines: Aircraft on asphalt

- Part 2, CVTs: The perfect gear

- Brabham BT46B - Ground Effect and the Fan Car, by Darren Galpin

- Eifelland - Periscope up!, by Mattijs Diepraam/Leo Breevoort

- Four-wheel drive - The Cosworth F1 car and the history of four-wheel-drive in racing, by Mattijs Diepraam

- Lotus 72 - The Lotus 72 Story, six years at the top, by Hrvoje Vrbanc

- Six-wheelers - Overtaken by history, the quick rise and fall of six-wheeled cars in Grand Prix racing, by Mattijs Diepraam

- Wings - The inventor and the invention, by Mattijs Diepraam/John Cross

Who?Jochen Rindt What?Lotus-Cosworth 72 Where?Zandvoort When?1970 Dutch GP (photo: Joost Evers) |

|

Why?

The summer of 1970 wasn't the once famous summer of love but to the Formula One audience it might be remembered as the summer of the Lotus 72. The Dutch Grand Prix was the first of four successive wins by the 72, the new and spectacular wedge-shaped car. Unfortunately Jochen Rindt died during practice for the Italian Grand Prix on September 6 and thus became the first posthumous world champion in Formula One. His death confirmed the reputation of Lotus: fast and innovative designs but also fragile and deadly.

As it turned out, the Lotus 72 was the overture to a design revolution. After its victory at Zandvoort things would never be the same. Formula One engineering started to developed at a furious pace. It became an era that sparkled with creativity and gave rise to startling innovations which, when all was said and done, had changed the shape of racing completely.

Wings: the start of a revolution

The leading image of Formula One in the 1960s was the slender cigar-shaped machine. Low air resistance was the main issue and mechanical grip the key to roadholding. 1966 was the first year of the new 3-litre formula. Maximum engine capacity doubled. Power grew rapidly (in 1966 the maximum output was about 290bhp, but in 1970 this had already risen to 430bhp). This changed the behavior of the cars and gave rise to the question of transfering this output to the tyres and onto the track. The tyres grew bigger for more mechanical grip. But something was still missing: downforce.

The solution: wings.

And wings they got. Computer simulation and calculation was non-existent, wind tunnels and aerodynamics were still in their infancy and expensive. Anyway, most teams lacked the resources to do much research, so engineering was a matter of trial and error. It mostly depended on experience and trust all would be solid enough to stand the test of the actual race.

At first wings were modest extensions on the front and rear of the cars, but during the late 1960s they grew taller and wider. The sky seemed the limit.

It had to go wrong. And so it did. In 1969.

There had been several incidents in which wings, struts, or the suspension (to which the wings were attached) collapsed. During the Spanish Grand Prix at the Montjuïc circuit Graham Hill crashed at high speed because of this. A couple of laps later Rindt's wing failed at the same spot. He ran full speed into the barrier, then into the wreckage of Hill and turned over. Remarkably, Rindt suffered only a broken nose and a couple off cuts and bruises.

But things could have gone worse. Far worse. If Rindt was lucky to escape alive, the spectators certainly were. At one moment Rindt's car nearly tipped over the barrier, behind which a big audience stood. There was nothing between them and the car. Hitting Hill's wreckage got him back on track.

Montjuïc 1969: Rindt's overturned Lotus 49, after crashing because of wing failure.

It was the end of the first wing era. Wings did reappear later in the season but were restricted in size and height and had to be attached directly to the chassis in a fixed position.

A star is born: the Lotus 72

In 1970 Lotus introduced a car that made the sigar-shaped cars suddenly appear obsolete. The Lotus 72 had everything no other Formula One car had up to then. Strangely enough it was not the car Chapman originally had in mind. He had been experimenting with two other projects, both of them not turning out the way he had anticipated.

The one project was the 4-wheel drive Lotus 63. This concept proved too complicated and drivers didn't like the car. Graham Hill called it a 'death trap'. The other was the Lotus 56, a turbine-driven car which competed at the Indianapolis 500 in 1968. Chapman developed the 56 as a potential F1 contender, part of his plan to have a single design to compete at both the Indy 500 and in Formula 1. But it was too heavy, too complicated and never competitive.

It was all typically late 1960s, early 1970s: a lot of trial and a lot of error.

The Lotus 72 was a 2WD Cosworth-engined car but not of a conventional design. It had many novelties, some of which were of great importance. Its unique wedge shape was derived from the Type 56. The water radiators were moved from the nose and split into two and situated on each side of the cockpit. This improved aerodynamic flow and moved the weight towards the rear end. The front of the car looked like a wing, a new approach towards airflow. Originally there were suspension problems, but these were solved after the car's debut in Spain. Then the car quickly showed its superiority.

In 1970 the classic sigar-shaped car was already past its high point. The Brabham BT33 was still the most conventional design in the field. It did well in the hands of Jack Brabham during the opening stages of the season, but started to decline during the second half.

Other constructors still used the basic form with the radiator in front, but the nose got flatter and more angular. Aerodynamics began to play a role and a faint sense of downforce started to emerge in the new designs. The March team, making its debut with the quite rectangular 701, even had wings on each side of the cockpit. We cannot compare these with the sidepods which Lotus introduced a couple of years later. In those days the ground effect and the importance of controling the air flow at the underside the car were not understood at all.

Nosing around

Before the Lotus 72 was introduced (and proved successful), all the GP cars looked more or less the same (as they do today – but instead of trial and error, nowadays it is the dictatorship of the wind tunnel). After 1970 an amazing diversity of shapes started to blossom. Suddenly out of nowhere cars like the 'lobster claw' Brabham BT34 and the 'tea tray' March 711 appeared.

Nürburgring 1971: Andrea de Adamich in the March 711 with the famous 'tea tray'. (photo Lothar Spurzem)

Paul Ricard 1971: Graham Hill driving the 'lobster' Brabham BT34.

These were at least remarkable designs. The Brabham tried to solve the problem of downforce by a broad front wing placed between the radiators. These were fixed in two 'shoe boxes' in front of both front wheels. In a way this would become, together with the triangular monocoque, the distinctive feature of the Brabham cars designed in later years by Gordon Murray.

One of the most distinctive parts of the human physiognomy happens to be the nose. The same holds for cars, including Formula One cars. From 1971 on there were two distinctive 'schools' as far as noses were concerned: the Lotus 72 'hammer head' school and the 'sports car' school. The first school created more downforce the second proved very effective in reducing the aerodynamic lift and drag induced by the wide rotating front wheels. Both schools fared well in the early 1970s. The hammer heads finally won when ground effect became the decisive factor for success.

Gordon Murray of Brabham became the apostle of the sports car nose. During the 1970s he designed a couple of very successful (and extremely beautiful) cars. As a matter of fact I dare say that the designs by Murray had a very personal style (just like Chapman's) in the way an artist can have a personal style.

'White beauty': the Brabham BT44 – Formula One construction at the brink of fine art.

Take a look at the Brabham BT44, which made its debut in 1974. We recognize the sports car nose and triangular shape characteristic of Murray's early 1970s designs. This would be developed further in the cars to come (successful trials and little error!). It is a clear and (in a way) simple design, showing that beauty (to give it a name) and effectiveness can go hand in hand! If the JPS Lotus was a 'black beauty', this was the ultimate 'white beauty'.

(And how about that other beauty, the red one? you might ask – I will talk about Ferrari later.)

In the early 1970s there was another designer who, just like Gordon Murray, had a very personal style, but lacked the technical genius of the latter. Luigi (or Lutz) Colani appeared on the scene in 1972. He created a remarkable, futuristic car; the Eifelland March. Colani's style is characterized by rounded, organic forms, which he termed 'biodynamic'. He claimed this to be ergonomically superior to traditional designs: "The earth is round, all the heavenly bodies are round; they all move on round or elliptical orbits. This same image of circular globe-shaped mini worlds orbiting around each other follows us right down to the microcosmos. We are even aroused by round forms in species propagation related eroticism. Why should I join the straying mass who want to make everything angular? I am going to pursue Galileo Galilei's philosophy: my world is also round."

The result of his philosophy looked like this:

The Eifelland March in 1972: Freud in Formula One design?

Colani's design was a car fully enveloping Rolf Stommelen: making man and machine literaly a unity. The car featured an air intake in front of the driver, with the air being guided around the cockpit to the engine. A single rear view mirror was mounted right before the driver and resembled a periscope.

Colani, it seemed, was guided more by science fiction and instinct than technical know-how. But no matter how futuristic the bodywork looked, beneath it lay a rather lame beast, the March 721. Both works drivers, Peterson and Lauda, discovered it was a hopeless design. There were problems with overheating, downforce and reliability. So after the beginning of the season Colani's spectacular shapes were soon reduced to more traditional shapes.

Brands Hatch 1972: the Eifelland March stripped bare.

Maybe Freudians in our midst see a distinct resemblance between the Colani interpretation of a Formula One car and the wish to return to the womb as a place of quiet and tranquility. But no matter what kind of philosophy or psychology we attribute to it, the Eifelland team was to be shortlived. After nine races and and no results the recources had dried up and that was it.

1970 – 1975: the rise and fall of the Lotus 72

Lotus had won the championship in 1970, but at what price? 1971 resulted in a desultory season. After the death of Jim Clark in 1968 Chapman was devastated, but the experienced and thoughtful Graham Hill kept the team together, made things work and even became world champion. No such thing in 1971. Chapman was again dismayed, but Emerson Fittipaldi was a young and inexperienced driver not quite able yet to carry the heavy load of leading the team back to succes. To complicate matters Chapman decided to keep on experimenting with the turbine car and four wheel drive. All to no avail.

1972 proved better: Fittipaldi became world champion and in 1973 he again had his chances, but he and Peterson, his new team mate, raced each other out. So Jackie Stewart picked his third and last title for Tyrrell.

By then the Lotus 72 had more than made its mark and other teams were following suit. McLaren introduced the M23 which was largely based on the Lotus. It was a simple and effective design, bringing Fittipaldi his second title and (in 1976) James Hunt's first. In 1974 the Tyrrell 007 showed clear inspiration from the Lotus concept and more manufacturers were to follow.

After four years of competition, the time seemed right for the 72 to be succeeded. Unfortunally its successor, the Lotus 76, proved to be a failure. Ronnie Peterson and Jacky Ickx reverted back to the good old 72. Peterson drove brilliantly and won three races. Ickx won a wet Race of Champions. But that was the best the old cars could do by now.

1975 turned out to be a disaster, the 72 design was five years old (an immense age for a racing car, even in those days). There were a lot of problems. The cars became unsuitable for the latest generation of tyres and the weight was too much rearward so the cars couldn't heat front tyres adequately.

Peterson's best result was a fourth place in Monaco, but his season ended with six meagre points. Ickx finished second in the Spanish Grand Prix at Montjuïc, but only after most of the field had crashed out of the race which was stopped halfway because the rear wing of Rolf Stommelen's car broke. He flew over the barrier amidst the spectators (it could have happened six years earlier). Five of them died. Montjuïc was never to be raced again.

Together with the swansong of the 72, a new approach towards racing emerged. Pushing the throttle as hard and long as one dared was not enough. Racing had become a more complicated business than that. A car was no longer as good as its engine power. In order to be fast one had to calculate, be patient, and work relentlessly towards perfection between man and machine. It still needed guts, but also extensive testing and technical know how. With all that a new type of driver came into view.

Second half of the 1970s: Ferrari on the rise again

That driver turned out to be Niki Lauda. He was as unromantic as any driver could be; a cool rationalist with a strong aversion towards any kind of puffiness. Today we would call him a nerd. March and BRM, his former teams, were not the instruments with which he could excel. Working with Ferrari he was able to sharpen his tools and make things work close to perfection. His success was for a large part the result of endless testing at the Ferrari test circuit in Maranello.

When Lauda joined Ferrari in 1974 the team had had a couple of bad seasons. The 312B2 coupled a strong 12-cylinder engine to a bad chassis. Ickx and Merzario struggled trough the 1973 season. The team showed up with the unfamous 'snow plough', but the car did not look good and did not do good.

But something was to come out of it, thanks to the tireless and determined Lauda: the 312B3. Both Lauda and Clay Regazzoni won three races and Ferrari was runner-up in the manufacturers championship. The new Ferraris had a characteristic nose carrying a broad wing on top of it. You could not classify the nose as the typical 'hammer heads' nor as the 'sports cars'.

The engine was a strong and reliable flat 12-cylinder. The suspension was also different from its predecessors with the front of the chassis being much narrower. The handling of the car was found to be inherently neutral, due to the transverse-mounted gearbox.

The Ferrari 'snow plough' 312B3; a constructor in search for new inspiration.

Things became even better in 1975, when Lauda won his first world championship. The next year he was halfway the season leading comfortably, when things went wrong at the Nürburgring. Lauda crashed, almost lost his life in a burning car and returned six weeks later at Monza as if risen from the grave. The rest is history. Hunt won the world championship with the (by now) old M23 and Lauda came out of the inferno showing unexpected human qualities, even uncertainties. He won the 1977 championship and left Ferrari in great discontent to go to Brabham.

Ferrari was to win another championship in 1979 by Jody Scheckter with the 312T4, nicknamed 'the slipper'. It was another remarkble car designed according to the now typical 312T concept. But it would become obsolete in no time.

Zandvoort 1979: Scheckter on his way to the title in the 'slipper' – notice the use of 'skirts' creating a vacuum underneath the car. (photo Willem Visser)

No matter the progress Ferrari made in aerodynamics (wind tunnels now in great use), the wing car and ground effect introduced by (again) Chapman and Lotus were on the rise and ready to change Formula One again. The flat engine was not suited to take full advantage of the ground effect. The 1980 season saw further aerodynamic progress by the Cosworth teams, while the updated version of the 312T4, the 312T5, was totally outclassed.

Six wheels: another brilliant trial turning out to be an error

Ground effect would become the main force in the evolution of Formula One. There is only one way and one shape this concept works best. It is all about physics and laws of physics, airflow and all that stuff. You can not fool these laws. They are great unifiers of all design. That is why all race cars nowadays look so much the same. Small details may look different, but the overall shape can only be 'one size fits all'.

This was not (yet) the case in the 1970s. Ground-effect cars were soon to change all this, but there were some interesting designs that tried to find new solutions for old problems. And the one and only problem in Formula One is of course: how to be fast and furious.

In 1976 there suddenly was the much talked-about Tyrrell P34.

Scheckter in 1976 driving the six-wheel Tyrrell P34, a successful trial turning out to be an error. (photo Lothar Spurzem)

It seemed such a good idea. Brilliant even! And it was outrageous! Give the car a sports car nose; make the front wheels as low as possible and you have superb aerodynamics with little air resistance in order to reach higher speed. But then you do not want to have two little front wheels. Lets make it four! This gives better mechanical grip and – in case of tyre faillure – it is even safer.

The car was the handiwork of Tyrrell's chief designer Derek Gardner. Its most striking feature was the use of four 10-inch wheels. The front-end layout was intended to "... minimize induced drag by reducing lift at the front and to turn that gain into the ability to enter and leave corners faster". The use of four small disc brakes required a special triple master-cylinder system, each feeding the brakes on one of the three axles. This was necessary as adjustments were required to control locking at the four front wheels.

Theoretically it sounded good and in a way it looked good. At least in 1976. The car even turned out to be a winner. In Sweden Scheckter and Depaillier finished first and second. In the constructeurs championship Tyrrell came third. Not bad.

But things did not remain that good. Scheckter realised the design would only be temporarily competitive. The special Goodyear tyres were not being developed enough by the end of the season. He left the team, insisting that the six-wheeler was "a piece of junk!"

In came Peterson. The car was tested in the windtunnel. It was even provided with electronic instruments to collect data that could be studied with computers. Quite extraordinary in those days!

So the P34 was redesigned around cleaner aerodynamics and became the P34B. It was wider and heavier than before. And it became clear the car was not as good as before, mostly due to the tyre manufacturer's failure to properly develop the small front tyres. Also, the added weight of the front suspension system did not do the car much good. Thus, the P34 was abandoned for 1978, and a truly remarkable chapter in F1 history ended.

The second wing revolution

So, six wheels were not the next breakthrough. Nor were the powerful twelve-cylinder Ferrari engines. The future was for wings, or better: the wing car. In 1976 the Lotus 77 made its debut. It featured a slimmer, lighter monocoque design and improved aerodynamics with repositioned radiators to aid better cooling. The front brakes were initially inboard, in line with its predecessors, but were moved outboard in a more conventional design part-way through the season.

The drivers, Mario Andretti and Gunnar Nilsson, were not all that happy with it. Parts broke off too much for their liking; the usual Lotus flaws. When asked what he thought Lotus needed, Nilsson answered: "A tank of petrol and a box of matches." But the 77 was only an intermediate design. Chapman had something cooking in his kitchen that made everyone look flabbergasted.

The appetizer was the Lotus 78: the first real wing car. It was now known that the air underneath the cars influenced the behaviour and grip. The teams started to experiment with 'skirts'; strips of rubber fitted to the sides of the cars to prevent air from coming under the cars.

Chapman, however, perfected this by creating a real vacuum underneath his 78. The sidepods were bulky constructions between front and rear wheels and shaped as inverted aerofoils which were sealed with flexible skirts to the ground. The radiators were embedded into the sidepods and the whole concept partly based on that of an aircraft. The intention was not to fly but to 'glue' the car to the track. This turned out to produce an enormous speed advantage in fast corners.

However, during the 1977 season the Lotus 78 suffered a lot of bad luck. On the other hand, a determined Lauda with Ferrari was more than eager to win the championship after his disastrous 1976 season. So Lotus had to wait one more year. Then the Lotus 79 made its debut and things fell in place with this 'black beauty'. It had everything the 78 lacked and a lot more. Andretti was the teamleader and Peterson (there he was again) became his reliable valet. It all went smooth and nothing could stop Andretti being the next champion. But just as in 1970 disaster struck at Monza. Peterson had a first-lap accident and crashed badly with his car catching fire. He was rescued from the burning wreck, but had suffered bad injuries to his legs. These proved fatal next day.

Andretti and Lotus had their titles, but again the price turned out to be unreasonbly high.

'Black beauty': the briliant Lotus 79 – the car that had everything no other car before had.

Nevertheless everyone jumped on the bandwagon and started designing ground-effect cars for 1979. Most cars were almost identical to the Lotus. Chapman meanwhile overplayed his hand by building what had to become the ultimate wing car; a car that 'was' a wing without using wings. The Lotus 80 proved a downright faillure and was withdrawn early in the 1979 season and replaced by the – then already more or less old-fashioned – 79.

Other teams copied and improved the concept, but cornering speeds became so dangerously high that flat undersides became mandatory for 1983. Part of the danger was the possibility of the sudden loss of ground effect. If the underside of the car has contact with the ground, the flow is constricted too much, resulting in almost a total loss of vacuum. To keep cars at a constant height the suspension became extremely stiff, making the drive a particular unpleasant experience.

In search of balance, constructors strove to have the centre of gravity in the middle of the cars. Fuel tanks and engine were placed as much as possible at the centre with the driver very much at the front. They also strove to keep the cars narrow, so they could optimize the vacuum area. Thus the drivers were prone to suffer terrible fractures of their feet and legs in case of an accident. Peterson's bad luck at Monza turned out to be a warning for things to come.

But that was not the only problem. Aerodynamics were still poorly understood. Some of the teams had little money but were very keen to find the holy grail of ground effect without too many costs. Extensive wind tunnel testing was expensive, so a generation of cars emerged that were designed as much by hunch as by any great knowledge of the finer details. The Arrows A2, which had to generate more ground effect than the original ground effect cars, illustrates this.

Zandvoort 1979: Jochen Mass driving the Arrows A2 in the rain – a car that scared the hell out of the drivers. (photo Willem Visser)

It was immediately dubbed the 'Buzz Bomb'. Theoretically, the A2 should have blown away the competition. It didn't need front wings. The bodywork maximized the area of low pressure under the car. Intakes and protuberances were kept a minimum.

As a matter of fact, it generated extensive downforce. But this came with a price: they were hard (alright, almost impossible) to handle. Not only was it hard to steer through corners, but it also suffered from 'porpoising' on the straights. This means that the downforce varied according to the ground clearance underneath. So the area of downforce wandered around and the car would alternately be glued to the track and suddenly released. It scared the hell out of the drivers. Mass and Patrese never knew what the car was up to.

It became clear that positioning and control of downforce was more important than the amount of downforce itself.

Epilogue

The 1970s were the era of Lotus. Without the Lotus 72 much of the changes we witnessed were not set in motion and the 79 seemed in a way Lotus' concluding masterpiece. During the 1980s Lotus little by little became a fading star; not illuminating the night sky like a supernova, but simply disappearing in obscurity.

Meanwhile new inventions were on their way. These did not influence the appearance of the cars too much. Basicly the (by now) traditional wing car concept was maintained. Big changes were to be found under the hood.

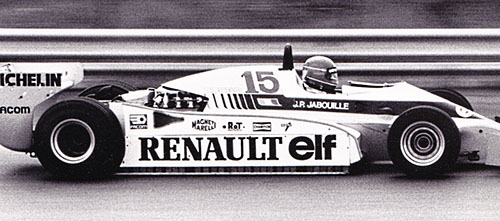

Renault had introduced the turbocharged engine in 1977. It didn't make much impression in those days. Among the many new ideas that blossomed, it seemed just another interesting trial, probably doomed to result in failure. But turbos worked, and worked well. In 1979 Jabouille won his first GP in (of all places) France and more success lay ahead.

In 1980 it became clear that the turbo engine might be the future. And so it was; the 1980s became the turbo era. An altogether different epoch, as it soon turned out…

Zandvoort 1979: the Renault RE10 – overture to the 1980s. (photo Willem Visser)