When Rindt became a Ringmeister

Author

- Lorenzo Baer

Date

- September 20, 2023

Related articles

- 1967 Eifelrennen - When snow fell on the 'Ring, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1968 Argentinian F2 Temporada - The quick dash of the Cavallino Rampante in the Argentinian Pampas, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1968 German GP - The class of the field, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas

- Nürburgring - Lords of the 'Ring, by Robert Blinkhorn

- Jochen Rindt - Fearless until the end, by Mattijs Diepraam

Who?Jochen Rindt What?Lotus-Cosworth 69 Where?Nürburgring When?XXXIII Internationales ADAC-Eifelrennen (May 3, 1970) |

|

Why?

1970 was certainly the year of Jochen Rindt. Despite the tragic death of the driver in the tenth race of that years' Formula 1 championship, in Monza, the title did not escape him in the three following rounds. As a consequence of that, Rindt remains until today the only posthumous F1 champion.

Jochen Rindt: the goals we have along the way

The Austrian's legacy was immortalized in this title, but the driver's story was built by many other successes achieved throughout his career. Although his six Formula 1 victories were obtained in the last two years of his life, between 1969 and 1970, his series of good results can be traced back to 1965 when the driver took his first big steps in the category. First with Cooper, then Brabham, to finally reaping his successes with Lotus, Rindt was undoubtedly one of the most talented drivers of his generation. This can be exemplified not only by his role in Formula 1, a category eternally linked to the driver's image, but his performance in other disciplines of motorsport.

The good results achieved in some endurance events, especially the victory in the 1965 24 Le Mans Hours, were remarkable in the Austrian's history, simply because these long-distance races were the greatest testing grounds for machines and drivers. But one of the categories that Rindt most insisted on demonstrating his talent was in Formula 2. Between 1967 and 1969, he had an average of three to four victories per year in the category, only counting the races valid for the championship; and if we add the non-championship rounds, this average rises exponentially.

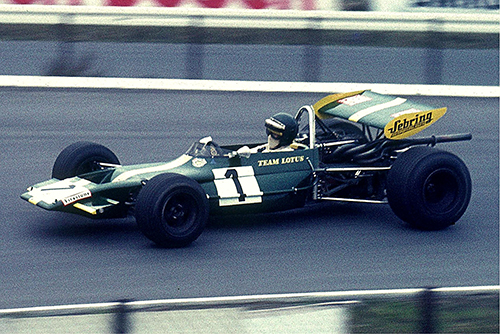

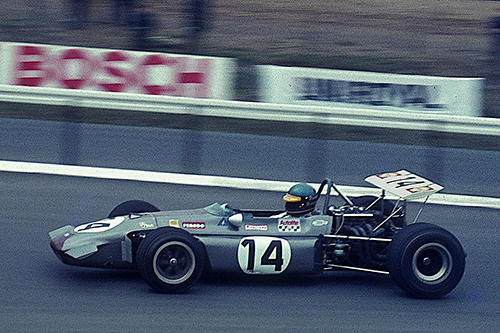

Jochen Rindt in the Lotus 69. (photo Lothar Spurzem)

Although all these results were of no use to the official F2 championship table (Rindt was already an official Formula 1 driver, so he was not allowed to score points in two single-seater championships simultaneously) they were trophies and victories anyway.

Among all these achievements, one that always escaped was a win at the Nürburgring Nordschleife. The driver had achieved victories there, in 1966 and 1967, but both in Formula 2 races on the dreaded circuit's ugly cousin: the Südschleife. Those weren't enough, as winning on the Nordschleife had always been one of Rindt's most coveted goals, and maybe not only for him, but for 90% of the drivers at the time. This was due to the simple burden that the feared track carried at the time: Monaco was the glamorous victory; Le Mans, the epic victory; and Nürburgring, the harsh victory. Winning on the 22.835m long circuit was the ultimate testament to any driver's skill.

But by the time of Rindt's first victory in that Eifelrennen of May 3, 1970, a long list of victories and failures was already behind him; and from there Rindt's story begins.

The 1970 Formula 2 Championship

The 1970 Formula 2 season was one of the most disputed in the category, with the battle for the title only settled in the last race at Hockenheim. Who got on top in the dispute was the Swiss Clay Regazzoni in a Tecno, who with 44 points became champion of the category and paved his way to Formula 1.

But the season can't be summarized in just one final race: throughout the eight official rounds that counted for the championship, in addition to a dozen more non-championship races, several drivers had their chances to shine, and to demonstrate their strengths and weakness, oscillations so common in F1 feeder series.

One of the most peculiar features of the 1970 F2 season was that it was almost considered a one-make championship, as over 60% of the field was made up of BT30 Brabhams.

In his Automovil Club Argentina example, Carlos Reutemann was among the many to campaign a Brabham BT30 in the 1970 Formula 2 season.

Despite this almost absurd amount of cars of the same make in several teams in the same series (this in contrast to the diversity of manufacturers in Formula 2 in the 50s and 60s), Brabham only reaped three victories in all, counting between the official and non-official rounds.

But that would seem insignificant compared to a car's other impressive data in the season: if there had been a championship for makes and chassis, the BT30 would have easily won. Why? Well, because even with that ridiculously low number of victories, nearly half of podium finishes were achieved by the cars manufactured in Chessington.

The Brabhams' biggest competitors during the season were BMW (6 wins), Tecno (6 wins) and Lotus (5 wins). In addition to relying on the development factor carried out over the previous years, both BMW and Lotus threw on the table another trump card to win as many stages as possible: to use graded drivers.

For example, a good part of BMW's victories belonged to Jo Siffert and Jacky Ickx (as the only non-graded driver of the team to stand out was Dieter Quester, who achieved great results in the final legs of the season); while those of Lotus were due to Jochen Rindt. The big exception to the rule was Tecno – and, as already mentioned, it seems that the Italian constructor's strategy paid off in the end.

The Eifelrennen

The history of the Eifelrennen dates back to 1922, as a German response, more specifically from the biggest automobile club in Germany, the ADAC (Allgemeiner Deutscher Automobil-Club e.V), to the popularity of the Targa Florio, which took place annually on the island of Sicily and attracted a crowd of fans every year. The answer sought to be so direct and explicit that the race was always scheduled for the same weekend as the Italian race.

The initial layout of the first four editions (1922, then 1924 to 1926) crossed a series of public roads, which together formed a circuit of approximately 33.2 km in length between the villages of Nideggen, Wollersheim, Vlatten, Heimbach and Hasenfeld. But due to several factors, among them the rapid development of competition cars in the second half of the 1920s, in addition to the precariousness of the track and facilities, which generated a dozen fatal accidents, it was decided to build a new permanent circuit.

The surroundings of the village of Nürburg were considered perfect for the new track. In addition to the topography of the site being ideal, it was close to one of the sections of the old circuit, in the nearby village of Niedeggen. Therefore, the lineage of the first four editions could be carried from place to place without major consequences.

The year 1927 saw the first official race at the Nürburgring. The V ADAC-Eifelrennen, which was contested this year by sports cars, saw the victory of the famous Rudolf Caracciola, in a Mercedes-Benz Typ S. This race quickly attested the success of the new track, and also popularized the trophy itself, which became the object of coveted not only by German drivers, but by those across Europe.

Over the years and decades, the Eifelrennen went through several phases, being disputed by categories of Sports Cars (1927 – 1929, 1949, 1954 – 1955), Grand Prix (1930 – 1939), GTs (1956 – 1958), Formula Juniors (1959 – 1963) and Formula 2 (1950 – 1953, 1964 – 1970).

It should be remembered that in the second stint as a Formula 2 event, between 1964 and 1968, the race was not held on the traditional Nordschleife but was instead relegated to the neglected southern section of the circuit.

Preparations for the 1970 Eifelrennen

Unlike 1969, the 1970 edition of Eifelrennen would not be an official leg of the F2 calendar; instead, it was downgraded to non-championship race status. It may seem that this detail would alienate most of the teams that competed in the regular season, but that was not really what happened.

In the pre-entry list released the week before the race, there were 41 entries! This represented one of the biggest single-seater line-ups in the history of the circuit and, for sure, was a pleasant surprise for both the expected audience and for the organizers themselves.

But, as we'll talk about later, of those 41, only 32 would actually show up for the test days and the race itself. Nothing that detracted from that edition of Eifelrennen, because even so, it was still a record number of competitors in the editions for F2 cars.

It can be assumed that much of this is due to the prestige element, which was already part of the mystique surrounding the race. In addition to being one of the trophies with the greatest history and tradition in Europe at the time, another factor that attracted the attention of the drivers was the prize paid by the ADAC, which served as a complementary incentive to all.

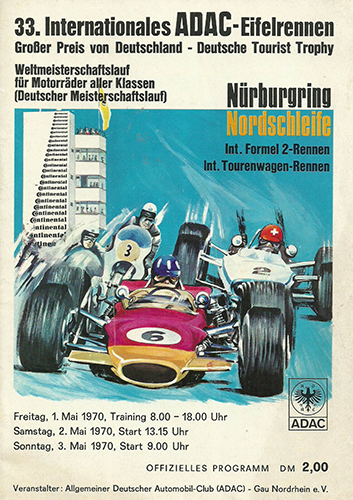

The poster for the 1970 race.

One of the first to confirm their presence was Jochen Rindt who, aiming to win the race that had always eluded him, would lead a team bearing his own name. To that end, the driver had given up racing in the Targa Florio that year, just to have one more chance to enter the Ringmeisters hall.

The Jochen Rindt Racing team (which was jointly managed by Rindt himself and Bernie Ecclestone) would take to the circuit in two Lotus 69s cars that, until then, had proved to be extremely competitive in the hands of the Austrian. For himself, Rindt had selected chassis 69.F2.4, the same in which he had already won the XXV B.A.R.C. 200 (at Thruxton) and the XXX Grand Prix of Pau.

An interesting detail about the team's two Lotus 69s is that these cars were the ex-Lotus 59s that Roy Winkelmann Racing had used in the 1969 F2 season. After changing hands, the cars went through an extensive program of upgrades which started by cutting the spaceframe center section out of the 59Bs and replacing it with a monocoque one, incorporating bulbous sides containing the bag tanks (which had become mandatory for all single-seaters from 1970 onwards). Besides that, another change was that the 'twin-nostril' nose of the 59 model was replaced with a chisel nose, in addition to other mechanical changes, which aimed to give greater robustness to the vehicle in racing conditions (like the strengthening of the front suspension).

The team's number 2 car would be driven by Briton John Miles, who was Rindt's teammate also in Formula 1 (but in the official Gold Leaf Lotus team). The Englishman had so far not been very successful in the 1970 F2 season, having achieved a 12th place at Pau as his best result in the four rounds so far.

Rindt's main opponent would undoubtedly be Derek Bell and his Brabham BT30. Even though being best known for his performances in endurance races (which ensured him five overall victories in Le Mans throughout his career) the Briton was experiencing one of his best moments in single-seaters, in the early 70s.

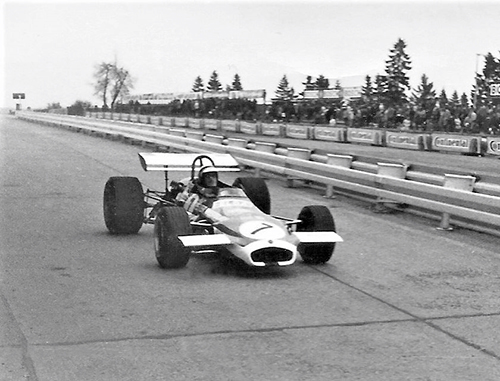

Derek Bell was the main rival to Rindt in his Wheatcroft Racing-run Brabham BT30. (photo Lothar Spurzem)

As part of the Wheatcroft Racing team, the driver had already clinched a F2 victory in the season, at the Barcelona Grand Prix held at the Montjuich circuit. In addition, he collected excellent results in the other three races held so far: two third places at Thruxton and Hockenheim and a fourth place at Pau.

Starting with the most emerging talents on the grid, the one who stood out the most was Brazilian Emerson Fittipaldi. Still far from the fame that the driver would reap in the following years, in the beginning of 1970 the driver from Tupiniquim was almost unknown in greater European circles. The only exception was England where, after an overwhelming campaign in British F3 in 1969, the Brazilian had won the title. After that, the driver was quickly promoted to European Formula 2 where his talent could truly be measured correctly. Driving a Lotus 69 from the Bardahl team (which gave the car a characteristic yellow tone), the Brazilian soon convinced the skeptics, even though he did not participate in the first two races of the season. With a reasonable sixth place at Hockenheim and a third at Barcelona, the driver was already quoted as one of the dark horses for victory in the 1970 Eifelrennen.

As one of the asterisks that I always like to make, it is worth mentioning that Fittipaldi's Lotus 69 was practically new from the factory, and no refurbished one like the ones from Jochen Rindt Racing. “Practically” in this sense applies because the car was originally delivered to Briton Jim Russell; but he only raced it in three races before passing it on to the Brazilian.

Kurt Ahrens in the BMW 270.

Of the local teams and drivers, two teams emerged as the favourites to keep the trophy in German hands: the first was obviously BMW which, after undergoing a complete overhaul, wanted a glorious rebirth in F2. This was due to the team's poor performances in the category between 1967 and 1968 using the Lola T100 and T102 chassis. Nothing but fiascos and illusory results led the team to look for a new path, a chance to take the cars from the Munich manufacturer to the winning path.

Phase one was the creation of a new line of models, still teamed up with Lola. From this came the BMWs 269 and 270, which were amazing evolutions compared to previous models. In the second phase, it was up to the development of a new engine, which could replace the venerable but unreliable BMW Apfelbeck. Thus was born the M12, which instead of generating the 225hp at 9500rpm of the Apfelbeck could deliver 250hp at 10,700rpm.

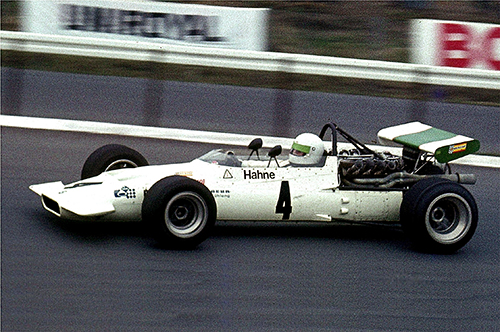

Hubert Hahne drove the 269 iteration of the Lola design. (photo Lothar Spurzem)

The team had gone through a testing phase in 1969, to find its ideal point of maturity from 1970 onwards. For this, the BMW team had also invested heavily in attracting F1 drivers to compete in specific F2 rounds, among them Jacky Ickx and Jo Siffert.

But for the Eifelrennen, the team could not rely on any of its top drivers, due to the migration of a large part of the drivers to the island of Sicily. The responsibility of carrying the team at the 'Ring would fall onto the shoulders of the home drivers, Dieter Quester (who along with Ickx and Siffert formed the official trio of BMW drivers for the season) as well as Hubert Hahne and Kurt Ahrens Jr (who had been the team's drivers for a few F2 races in the late 60s).

But that wasn't the only chance for the home nation to retain the win, because as I said earlier, there were two strong German teams in the running. The other contender materialized in the form of Eifelland Wohnwagenbau which had the German star Rolf Stommelen as its main driver.

Rolf Stommelen in the Eifelland Brabham BT30. (photo Arno Michels)

The name Eifelland would become known in 1972 after the team's disastrous adventure in Formula 1 that year, but long before that, Eifelland was a reasonably solid project in F2 and F3 powered by motorhome magnate Günther Henerici.

The team achieved modest results in the races it competed in these categories, something that was expected, due to the opponents that the Eifel-born team had to face in more attractive races, where the most professional and experienced teams on the grid usually appeared (such as the Eifelrennen, the Deutschland Trophäe or the Pokalrennen).

Even so, nothing that would disturb the competitive spirit of Eifelland and Henerici for that edition of the race: three cars would be taken by the team to dispute the race: a Brabham BT30 for the aforementioned Stommelen, a March 702 for Helmut Gall and a Brabham BT23C for Bernd Terbeck.

In addition to all those highlighted above, there were a dozen more drivers who really had a chance of winning, or at least of reaching the podium in this race – many of whom would become well-known names in the following years: Argentine Carlos Reutemann who since 1968 had been presenting consistent performances in F2 (in the Eifelrennen, he would race an Automobil Club Argentina Brabham BT30), Swede Reine Wisell who was another seasoned driver in F2 also showed up in the cockpit of a Chevron sponsored by the Publicator Racing Team.

Reine Wisell in the Publicator Chevron B17C. (photo Raimund Kommer)

Two other names that also deserve to be mentioned and that were on that grid are Australian Tim Schenken, who entered the fray with a semi-works Brabham BT30 (semi-works because the official Brabham team used the pseudonym Sports Motor International) and John Watson, who also had a Brabham BT30 that ran under the driver's own banner.

It is worth noting that all the cars (with the exception of the BMWs) were equipped with Cosworth FVA engines.

A sound amidst the woods

The track was cleared for the cars two days before the official start of the race, so that the drivers had time to acquaint themselves with the track conditions. Even though a reasonable number of drivers were already acquainted with the treacherous conditions of the track, no driver ever felt 100% prepared to race on the challenging circuit, so any chance to do some timed reconnaissance laps was always welcomed.

On the 1st of May, track conditions were ideal, with the dry surface being perfect for novices to get their first taste of the Green Hell. Incredible as it may seem, most of the cars went by that first day unscathed. But excluding himself from most was Ronnie Peterson, as on the first warm-up lap, his Malcolm Guthrie Racing March 702 suffered a broken wishbone. Even if it wasn't a worrying problem, changing the part took longer than expected, which deprived the driver of returning to the track that day.

Ronnie Peterson practising in the Malcolm Guthrie March 702. (photo Lothar Spurzem)

Who did better on the first day was Peter Westbury with a Brabham BT30 - the Brit pinned down a time of 8.10.5. Nothing that could discourage Rindt who got very close to the time posted by the FIRST team driver. It was clear that the Austrian would not let this victory slip away again.

The following day, one of the hallmarks of the twisty circuit appeared: the unpredictability of the weather. The track was now wet, in one of its most challenging conditions, forcing drivers to exercise caution at every turn on the track.

This second day of trials served to say one thing: this weekend would not be good for Ronnie Peterson. That's because the Swede crashed his newly repaired car after losing control on the circuit's slippery surface. Another one who had problems was Brian Cullen with his Brabham BT23C. Both were the only drivers present who failed to line up for the official start the next day.

Ronnie Peterson would not start the race in his March 702. (photo Udo Klinkel)

That Sunday, May the 3rd, thirty cars took their respective positions on the starting straight of the Green Hell. The race would be 10 laps long, totaling 228.35 kilometres. The distance wasn't what worried the drivers the most at the start, but the conditions of the track: even with the rain having stopped overnight, the track was still reasonably damp, which didn't help the drivers much throughout all the jumps and drops of the 22.835km circuit.

Even so, it was decided that the race would be carried out normally and once the flag had dropped the thirty cars shot towards the Südkehre. Rindt quickly took the lead from Westbury, making it clear that this time, victory on the Nordschleife would go to Austria.

The field going into the Südkehre on the first lap.

The Lotus began to build an advantage, while the Briton's Brabham BT30 began to lose ground. Things got even worse for Westbury when he lost control of the car, the driver spinning on one of the wet parts of the track. Fortunately, he successfully recovered from the error, saving the car from further damage.

Those who were not so lucky (or skilful) to avoid the pitfalls of the treacherous track were François Mazet and Kurt Ahrens Jr, who also spun but only ended up on the unprotected sides of the track. In addition to being the first retirements in the race, Ahrens' accident served as the first sign of the misfortunes that the BMW team would have to go through the race.

While some had problems adapting to the conditions on the damp tarmac of the Nürburgring, others took the opportunity to put on a show of skill: Jochen Rindt sought to widen the distance between himself and the rest of the field, but rookie Emerson Fittipaldi made a gala presentation by staying on the tail of the Austrian for the entire first lap.

In the second lap, the race underwent the changes that would practically seal the final classification, as a battle formed between Derek Bell, Rolf Stommelen and Emerson Fittipaldi that quickly turned into two small skirmishes between the Brazilian and the European drivers.

Dieter Quester was BMW's star driver in its Eifelrennen line-up but proved to be unlucky. (photo Lothar Spurzem)

The first to face the challenge was Derek Bell who, taking advantage of his enormous experience in European car races, overtook the Brazilian a bit further down into the second lap. Then came Stommelen, who had some hard work to take the third spot from the Brazilian.

This was due to the fact that Stommelen got off to a bad start, dropping a few places and being forced to pass cars slower than him in order to get back to the pack at the front. The German wasn't shaken, as he knew the Nürburgring shortcuts as the palm of his hand, and after one lap, he was already back up in fourth place. This quickly turned third, as he took advantage of a small mistake by Fittipaldi.

If Fittipaldi was surprising, two other golden boys didn't do well in the race: Tim Schenken and Reine Wisell. Even though they had cars from completely different brands (the Brabham BT30 and Chevron B17C, respectively), the two suffered with their machines, which were plagued with mechanical problems. This limited the drivers who only managed to fight for midfield positions down in the pack.

Meanwhile, BMW were stuck with bad luck for a second time when Hubert Hahne's car had damaged its exhaust pipe on the second lap. And the third time was not long in coming, when two laps later, Dieter Quester was forced to retire due to problems with the fuel pump. A very forgettable weekend for the Munich team.

Peter Westbury produced a fine recovery drive in his Brabham BT30. (photo Waldorf Statler)

Going back to the race, Peter Westbury had already recovered from his spin and, taking advantage of the problems and slip-ups of the other drivers, had the first few positions back in his sights. But to reach them, there was still a long way to go as Rindt, now followed by Bell, Stommelen and Fittipaldi, distanced himself from the rest of his rivals.

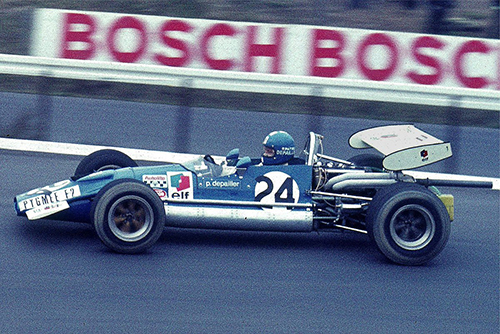

As a sideline, another drama was taking place, as Pygmée (which at the time was already a traditional constructor of F2 and F3 cars), suffered the same fate as BMW: none of its three drivers were going to finish the race: Jean-Pierre Jabouille had bearing problems on the first lap; Patrick Depailler had a fire in his car on the second lap; and the team's chances were finally over when the last surviving car, Patrick Dal Bo's one, also suffered from bearing issues on the sixth lap.

Patrick Depailler was one of three French drivers to race the MDB15 chassis for Constructions Mécaniques Pygmée. (photo Lothar Spurzem)

More than halfway through the race, Rindt had disappeared over the horizon, his only companions being the latecomers that the Lotus driver overtook along the way. His teammate, John Miles, could not offer any help in this ungrateful task, as he found himself trapped in the middle of the field.

At that point, on the seventh lap, only 16 cars were still on track and some of these were already a lap behind. Rindt continued to press on and on the ninth lap, the driver set a new record for F2 cars on the circuit, with a time of 8.16.2, at an average speed of 165.7kph.

That magnificent lap was enough to silence what was left of the opposition and it was up to the driver to take the car to the finish line safe and sound; and so he did, after 1 hour, 23 minutes and 54.7 seconds. The Austrian had finally earned his Nordschleife victory and perhaps any shred of doubt that still existed about the driver's talent disappeared. This was indeed Rindt's year!

Derek Bell finished second, twenty seconds behind the Austrian. Rolf Stommelen would bring home joy when he crossed the finish line in third place. Fittipaldi did not make it to the podium, as he completed the ten laps in fourth – but nothing that detracted from the Brazilian's performance, which demonstrated that he could fight on equal terms with the great talents of the European circus.

Of the thirty cars that started in the race, only thirteen were classified, and of these, only 10 were still on the same lap as the leader at the chequered flag. Nürburgring had taken its toll once again.

Why to read me? Present and future issues of the 1970 Eifelrennen

As an epilogue, the XXXIII Eifelrennen served to expose two things: the first was the reaffirmation of the genius of Jochen Rindt, who demonstrated that he could adapt to the most diverse circumstances and track conditions to get the best out of them; in addition to the fact that with this victory, the Austrian's superiority in F2 would continue to last.

F2 was one of his favourite hobbies in which the driver committed himself with a great deal of dedication. If victories came so naturally, why stop? For drivers like Rindt, Clark and Stewart, Formula 1 and 2 went hand in hand. They did not follow the stereotype of 'main category' and 'feeder category' but rather, they understood them as testbeds, of places where they could get involved at a very different level from that imposed by the increasingly professional environment of F1 – it was something like going back to the grassroots once again.

The second point concerned the Nürburgring circuit itself. The Eifelrennen served as a reconfirmation of existing concerns, about how the track was outdated compared to other major European venues.

Even with the victory, Rindt spoke openly about how dangerous the track was, becoming a great ally of the biggest advocate of safety in F1 – and motorsport in general – at the time: Jackie Stewart. As a result of this speech, the 1970 German F1 GP was held at the Hockenheimring, forcing the track in middle of the Eifel mountains to undergo a major restructuring project.

This was undoubtedly one of the first thuds in the history of the Nordschleife, and certainly the first sign that the track's destiny was sealed in the near future. Even with all that, much of the concern about the circuit would be swept under the table. However, on one fateful day in August 1976, the time bomb had zeroed, and both the Nürburgring and motorsport would never be the same afterwards.

Sources

- ADAC Nordrhein e.V.

- The Fastlane

- OldRacingCars

- MotorSport Magazine: Formula 2 Review, June 1970